Last week I made a snarky remark about Claudine Gay and plagiarism. Upon sober reflection, I realized that it was unfair of me to focus my ire on her when the problem of plagiarism is pervasive. I thought the topic deserved a post of its own. So here it is!

It has been grimly fascinating to watch, in real time, as the talking points have coalesced around the Claudine Gay plagiarism debacle. In articles and on social media, in op-ed pieces (D. Stephen Voss, the TA whose words Gay stole, speaks up for her here), and in Harvard’s own investigation of Gay, Gay’s defenders claim that she is guilty of mere “improper citation” and “duplicative language.” I don’t know about you, but I find the “improper citation” and “duplicative language” excuses unpersuasive because, first, Gay did a lot worse than improperly cite sources, and, second, “improper citation” and “duplicative language” are plagiarism too.1

And then it came out that the wife of Bill Ackman, one of Gay’s accusers, had also plagiarized in her dissertation (in a total middle-school move, she copied from Wikipedia verbatim). Awkward! Suddenly Ackman’s attacks on Gay were defanged. At the same time, because Gay’s defenders had minimized her plagiarism, they couldn’t criticize Ackman and his wife without being hypocrites. It is a bad look to claim that plagiarism is wrong when our enemies do it, but normal and forgivable when the offender is on our side. Fortunately, there is an easy way around this conundrum: We need only acknowledge that all plagiarism is stealing, and no matter who is doing it, it is always destructive and wrong.

Questions

Plagiarism may be obscene, but it differs from obscenity in one important way: We don’t always know it when we see it. Or, rather, we don’t always agree about how we should deal with any given case—whether we ought to punish it, or whether we should forgive it, treat it as a learning experience, pretend it didn’t happen, or make excuses for it. If we want to make fair decisions, it can be helpful to think about cases of plagiarism without regard to who the perp is or to whether s/he is on our side of the political aisle. To that end, consider four cases of plagiarism I have encountered in my years as a teacher and editor, and then ask yourself how you would handle them:

Case 1

Amy2 was a student in my colleague Beth’s tenth-grade English class. Amy struggled with her writing. Not only did she have trouble creating cohesive paragraphs and arguments, but her sentences also suffered from frequent and serious spelling, punctuation, and grammatical errors. Amy’s rough draft for her research paper was typical of her previous classroom work. However, her final draft had a clear argument and was written in nearly error-free prose. Beth suspected that Amy could not have produced this paper on her own, and so she asked Amy about it. Amy burst into tears and said that her mother had rewritten the paper and had forced her to turn it in as her own work. Because Amy admitted what happened right away and obviously knew it was wrong, Beth decided to treat Amy’s rough draft as her final paper, and to grade it accordingly, but to impose no additional penalties.

Case 2

When I was in graduate school, I was the TA for a professor, Charles. For the first assignment of the year, a student, David, turned in an essay whose middle section sounded like it had been lifted verbatim from a scholarly work. Charles called David into his office and confronted him. At first David was angry and defensive, but he eventually admitted that he had copied two paragraphs from a book. Charles gave David a failing grade on the paper and, because David was a freshman, he imposed no other immediate penalties. However, Charles put a note in David’s file documenting what had happened, and he made it clear to David that if he plagiarized again, he would be expelled from the university.

Case 3

My friend Ellen was an adjunct English professor at an elite university. A student, Frank, who was a senior, turned in a paper on Heart of Darkness. Ellen recognized at once that it had been copied—both its language and its ideas—from the CliffsNotes to the book. Ellen wanted to give Frank a failing grade for the semester because of such a flagrant act of plagiarism, but the university wouldn’t agree to this. Ellen then insisted that Frank should at least receive a failing grade on the paper. The university tried to persuade her to let Frank rewrite the paper for a better grade. When Ellen refused, Frank’s rabbi called Ellen to plead Frank’s case. In spite of this pressure, Ellen gave Frank an F on the plagiarized paper.

Case 4

When I was a copyeditor at an academic journal, a paper by a well-known scholar, Professor Gray, was accepted for publication. In the course of editing and fact-checking, we discovered that nearly 75 percent of the paper consisted of unattributed direct quotations from a book in French by another author. Gray had cited the book once in her footnotes, but she had translated long passages from it into English and presented them as her own work in the paper.3 Some professors on the editorial board wanted to keep quiet and publish the paper as-is, while others wanted to reject the paper. A compromise was eventually reached: We kept quiet about what had happened and published the paper, but we placed quotation marks around all the quoted material.

Thoughts on Why Plagiarism Is Wrong

The most common argument against plagiarism is that students cheat themselves out of learning information and skills they will need in the future. When Amy’s mom rewrote Amy’s paper for her, she robbed Amy of the opportunity to work on her spelling, punctuation, and grammar with Beth’s help and guidance. Similarly, David, at the very beginning of his studies, lost a chance to develop two skills crucial to success in college and career, clear writing and logical thinking.

Even so-called minor cases of plagiarism are morally shady. After the revelations about Gay came out, some of her allies noted that when one writes long pieces, organization can be a challenge—and that it is surprisingly easy to cut-and-paste someone else’s words into the document and present them as one’s own by accident. To which I say balderdash. Putting quotation marks around someone else’s words after you have pasted them into your article is not onerous or confusing. It might be boring, but it’s part of the job, the same as charting is for doctors or documenting billable hours is for lawyers. Plagiarism permits writers to be sloppy and deceptive, when readers have a right to expect precision and truth.

Amy’s story and my experience as a copyeditor illustrate a more serious problem: Plagiarism can inflict a moral injury—“the damage done to one’s conscience … when that person perpetrates, witnesses, or fails to prevent acts that transgress one’s own moral beliefs, values, or ethical codes of conduct.” Our cultural norms around plagiarism sometimes force people with less power and status—kids, adjunct professors, lowly copyeditors—to submit to something they know is wrong, simply because those in power impose it on them. I have sometimes wondered about Frank’s parents, who defended him instead of being disappointed in him and expecting him to take responsibility. Worse, they apparently suborned their rabbi to badger Ellen into letting Frank off scot-free. How was the rabbi able to justify that act to himself, morally and religiously?

Relatedly, when we wink at acts of plagiarism committed by members of “our team,” we may reinforce unjust class and power structures. As the many Harvard students who have been expelled or ordered to rusticate for offenses less serious than Gay’s can attest, it is unfair when the rich4 and powerful enjoy leniency that we deny to everyone else. Similarly, Gay’s former TA, whose words she plagiarized, admits in the interview cited above that he’s “not comfortable answering” the question of whether Gay should have been fired rather than simply allowed to resign, because

Claudine Gay was an immensely successful political scientist and university administrator. I’m off in the trenches teaching two-hundred-person undergraduate introductory classes. These questions of what should happen to Claudine Gay—we’re so far beyond my pay grade.

In any other situation, we would object to a boss stealing an underling’s work, especially when the boss is so powerful that her victim feels he can’t speak up afterwards.

Finally, plagiarism is stolen valor. People who copy the words and ideas of others and present them as their own seize an unfair advantage for themselves. They get all the glory and do none of the work.

Ideas for What to Do

Thanks (/s) to ChatGPT and similar AI technologies, plagiarism is only going to become a worse problem going forward, unless we change both our approach to education and our attitude about copying others’ work.

We should change how we teach. Beginning in elementary school, teachers should help students practice citing others’ work, so that it becomes automatic.5 For example, instead of a single lesson on proper citation before students begin a research paper, I would love to see students doing frequent, quick drills throughout the year on how to use quotation marks and to footnote sources. Teachers might also choose to teach writing using the flipped classroom: Students would do their research online at home, and then they could draft their paragraphs in class, with wifi disabled and under their teacher’s guidance. It can also help to make students accountable to each other in group work, so that peers would be advocates for academic integrity too. Students often respond better to the opinions of their friends than they do to the edicts of their teachers.

We should change our requirements. As this article argues, “pressure elicits cheating.” Put simply, “publish or perish” may encourage young academics to turn to plagiarism to help them churn out more papers. In fact, many careers could easily dispense with requirements for scholarly research. To take one example, clinical psychologists conduct therapy but don’t perform research; why, then, are they required to do original research in order to become credentialed for a career that uses such different skills? If we were to eliminate this requirement and switch to practical training for clinicians who see patients, we might greatly reduce the prevalence of plagiarism and academic fraud.

We should change our attitude. Couldn’t we please agree that stealing other people’s words and work is shameful, petty, low-down dirty-dog behavior? And that when someone we care about—or someone on our side of the political aisle—engages in it, we should be more, not less, outraged?

To that point, I’ll close with a story. When I was in high school, I had a hopeless crush on this guy I’ll call Henry. We had a chemistry exam coming up, and my class was in the morning, while Henry’s class was in the afternoon. Henry asked me to tell him what was on the exam. Because of my stupid crush, I was tempted, but I told my best friend about his request, hoping to be talked out of it. Her response was immediate and unambiguous: “Don’t you dare! That’s cheating!” (I agreed with her and didn’t tell Henry what was on the test.) She was a true friend to me that day.

True friends expect the best from us and help us to become better people. Instead of excusing bad behavior, we ought to be feeding the good wolf and holding those we care about to high standards. It is tough and takes courage, but this is how we show real love.

How about you, readers? What do you think? Is plagiarism always wrong, or is it ok in some circumstances and when done by some people? (Yes, I recognize that that is a tendentious question.) How should we deal with plagiarism? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

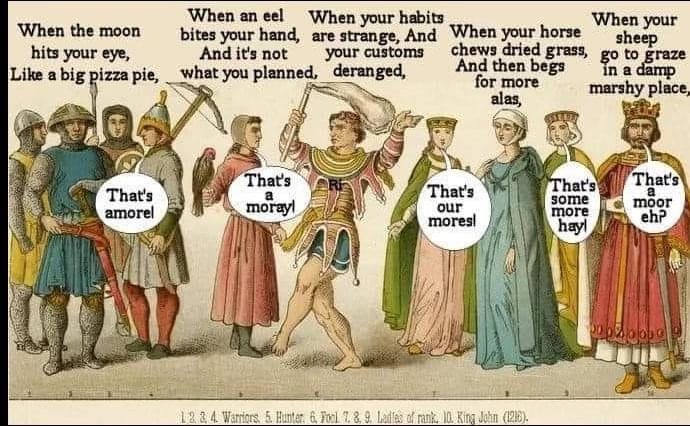

In contrast with plagiarism, where individuals steal the work of others for their own advantage, parodies, memes, and allusions are ways we build community through sharing and appreciating ideas and jokes other people have made up. For example the joke below, which my friend Laura posted recently:

And then there’s this version, which my daughter shared with me:

For a counterargument, I recommend John McWhorter’s article “We Need a New Word for ‘Plagiarism.’” McWhorter makes the reasonable point that the term “plagiarism” comprises two misdeeds that differ greatly in their seriousness: Stealing someone’s ideas and presenting them as one’s own on the one hand, and merely copying someone else’s words on the other.

I agree with McWhorter that the first form of plagiarism is much worse than the second, but I disagree with him when he says this “cutting and pasting” is no big deal. Taking someone’s words may be more like shoplifting than grand larceny, but it is still stealing, and we should not be excusing it.

All names in these examples are pseudonyms.

Most academic journals don’t do any fact-checking. I suspect that Professor Gray thought she could get away with it. She didn’t know that not only did we fact-check every paper, but that nearly everyone who worked at the journal could read French. D’ohhh!

In an op-ed defending herself, Gay gives the impression that she grew up poor, calling herself the “daughter of Haitian immigrants”—but neglecting to mention that she comes from one of the richest families in Haiti and attended elite private schools for her entire academic career.

Of course, all teachers stress the importance of academic integrity. However, as is clear from the people mentioned above who accidentally cut-and-paste others’ work into their documents, kids also need specific instruction, help, and practice to learn how to give proper credit every time they cite others’ words and work.

So, here are two thoughts I've been having on plagiarism.

First, I've seen very little acknowledgment that plagiarism is actually not a universal rule. It's obviously heavily condemned in education, academia, and journalism but less so in other fields. I'm an attorney, and 95% of what attorneys do is plagiarize. If you need to write a motion to dismiss, the first thing you do is find another motion to dismiss that you, someone else at your firm, or just someone else wrote. You then proceed to change as little of it as you can (which still is usually a lot), and you certainly don't cite, quote, or attribute the portions of the motion you are copying. When I started my most recent job, I actually got scolded for writing a report from scratch rather than using a model. I've even seen suggestions that it could be unethical to do so since you are billing your client for work you don't need to do.

While attorneys do frequently use quotations and cite sources, it isn't for plagiarism reasons, but because Judge Cardozo or Learned Hand saying something carries a lot more weight than a random attorney saying it, and you want to invoke their authority (either as controlling authority if it is a higher court or as persuasive authority if it is a non-controlling court or notable jurist).

This was roughly the case when I worked as a computer programmer c. 2000. While there are obviously IP concerns, and certain licenses require that you include comments or other acknowledgments, there was a lot of "recycling" code in ways that would constitute plagiarism in academia. I'm assuming this comes up in other fields, too. In most fields, if you are working on the June TPS report, do you start from scratch or pull up the May TPS report and work from that? And if it is the latter, do you quote and cite the May TPS report? I doubt it.

The other thought I've had, which you somewhat touch on in your article, is that rules against plagiarism really serve different functions when you are talking about students vs. academics/journalists. The goal with students is to ensure they are doing and understanding the work, which they are not if they are plagiarizing. You mentioned "cheating themselves," but it also cheats other students. This can either be through direct ranking (you don't want to miss being valedictorian because someone else plagiarized to get better grades) or through diminution of the credential (if Harvard starts spitting out a bunch of lousy graduates because they all plagiarized rather than learning the material, pretty soon a Harvard degree will be worth less). On the other hand, the problem with academics/journalists plagiarizing is stolen credit. If you come up with a good idea, you want credit for it so that it can help you advance. You don't want someone else taking it as your own. This is less of a concern for students, particularly at lower levels. No one's job prospects depend on whether they were cited in a 10th-grader's social studies paper.

I think this plays into John McWhorter's call for a distinction between stealing ideas and stealing words. If we are talking about a student, you care about both because both count as part of the assignment. On the other hand, I could see caring less about stealing words when it comes to an academic/journalist. The goal there is for them to come up with and spread new and interesting ideas. The words are just a tool they use for doing so. If you steal an academic/journalist's ideas, you have really stolen something of value. Words, less so. In fact, it may make sense to let academics/journalists steal words, particularly reasonably boilerplate words, for the same reason attorneys do it - to save time. If you have a brilliant academic, I'd rather have them spend their time doing research and thinking (or teaching students) rather than figuring out a novel way to phrase a sentence that 100 people have said before them.

At least one of Gay's alleged plagiarisms was her summary of a statute. It was close enough to the source that she probably did copy it, but it was also banal enough that I have a hard time seeing why, from a broader perspective, it was wrong for her to do so. It was an efficient summary. There were also only so many ways to summarize the statute without having to intentionally make your language bulky and inelegant (which includes adding a bunch of quotation marks and citations), which serves no one. Given how banal the description was, saying that she "stole" the language from the original author reminds me of a lot of the "business method" patents in the 2000s, where you know there was nothing creative about the solution; it's just that the patentor was the first person to come across the problem. IIRC, these patents have largely been invalidated and are at least much harder to get.

This isn't really intended as a defense of Gay. Mainly because I don't care to defend her, but also because, whether or not the rules make sense, you are generally expected to play by them. However, it is intended as a call to rethink whether plagiarism rules actually make sense in the context of academics and journalists or whether we should focus more on stealing ideas than language (poets can still complain about plagiarized language).

I do not, at all, in the strongest of terms, view the argument against plagiarism as wanting not to cheat students out of learning. Plagiarism is stealing and deceit; lying, cheating, and stealing. The argument against plagiarism is that it is wrong.

How to react may depend. With a high school student, as in case #1, surely the response obviously better than any of the listed options is to talk to the parent and kid together while giving an F on that paper. This addresses two questions, 1, did the kid just turn on the waterworks and come up with a tale to shift blame and gain sympathy? 2, does the mom know that now you and all of the other teachers now will never trust the kid or the kid's work again? And it is an opportunity to lay out transparently for the two of them together that 3, if the mom did not actually do that, she needs to deal with her kid's lying and underhandedness; 4, if the mom did do that, impress upon the kid that she (10th grade!!) should have her own integrity and not be a liar and a cheat like her mom; and 5, I guess maybe try the argument about not missing the opportunity to learn by doing the assignment, not that I think it's going to do any good in that case. Still, a huge missed opportunity to teach that kid crying isn't an excuse and neither is 'my mom made me do it'.

I lived through a version of case #3, except I was regular faculty, it was a grad school class, most students international, and the outcome was messier. The submitted work was clearly copy-pasted (varying fonts, colors, etc.) and the student was international. I flunked him and told the program director, since I wasn't sure who needed to take the other steps by policy. Nonetheless, he raised a huge stink, how could he know, how unfair it was, something something cultural something, you can't give me an F.

This was a near-Ivy school, selective program for early mid-career professionals. The program director was solid and never gave me any grief. The administration took the student's side and wanted a 'compromise'. The program director never suggested I change anything, took over all discussions with the powers that be, kept the heat completely off me, stood up for integrity and so forth. Looking back, I did not realize the pressures that must have been exerted. The brouhaha dragged on for a couple of semesters. Ultimately I suppose the administration got their compromise, in a way, since I think he was suspended for a semester then allowed to complete the program (by the book, he should have been kicked out). The process was the punishment for the department, as well as I think not doing me any good. No one blamed me exactly but it was a bummer, annoyance, long-running aggravation, and there I was, inextricably part of it.

This was roughly 15 years ago, I guess. Even then, even at an 'elite' school and in an 'exclusive' professional program, the so-called leadership had no thought of setting standards and requiring people to live up to them. It was coddling and condoning and keeping that tuition coming into the coffers, fairly shamelessly. It's worse now.

And finally, a story from the real world: Working elsewhere (not teaching), I was recruiting for staff and required short-listed candidates to submit work samples. One of them sent me a slightly edited document that, in fact, I myself had written. She didn't get the job.