Art I Liked at the Ashmolean

In Praise of Amateurism

I have always been a music person rather than an art person. I have no talent for painting or drawing and have never taken an art history course, so I used to be intimidated by art museums. While I know what I like, I lack a “professional” vocabulary to talk about art.

Two lucky breaks opened the world of art to me. First, I moved to Washington DC, where the world-class museums of the Smithsonian are free. When museums are free, you don’t feel as though you need to see everything in order to get your money’s worth.1 You can pop in to a free museum to visit a favorite painting and then just leave—there’s no need for an exhausting three-hour forced march through the whole place. The paradoxical result of my not feeling like I had to spend hours in art museums was that I actually wound up spending more time in them, to visit favorite pieces and occasionally check out something new.

The second lucky break was that my mother-in-law, who studied art history in college, developed a program to teach visual literacy to Head Start moms, with the idea that if they had a way to talk about art, they would want to bring their kids to the free museums for a playful time looking at and talking about art together. As it turns out, this approach works well with daughters-in-law too!

Today I am unapologetic about my amateurism—“amateur” means lover, after all, and I love looking at and reacting to art, even though I don’t have official training. I thought I’d share some depictions of people and animals from a recent visit to the Ashmolean Museum, a wonderful free art museum in Oxford, England.2 In what follows, the names, dates, and quotations about the paintings, household items, and sculptures come from the excellent wall texts at the museum. Thank you, curators!

Playful and Practical Objects

The Ashmolean boasts an enormous ceramics collection. Philistine that I am, I normally zip through it on my way to the paintings, which I consider more interesting. But this time my attention was arrested by this charming lady:

This is a gravy boat from the seventeenth century. When you fill the pot, this saucy lady takes a bath! An interesting historical detail is apparent in this image: back then, European people never, ever got completely naked. It was cold in those drafty houses! Ladies wore shifts underneath their petticoats and dresses, and, as you can see from the transparent light-blue shift this ceramic lady wears, they even bathed in them. In fact, eighteenth-century erotic novels like John Cleland’s Fanny Hill3 refer to Fanny and the other courtesans as naked when they are still wearing their shifts, and the whole point of John Donne’s delightful poem “To His Mistress Going to Bed” is to convince her to take that shift off and embrace “full nakedness! All joys are due to thee / as souls unbodied, bodies uncloth’d must be / to taste whole joys.”

On to the next practical, playful object. Can you guess what this is?

It’s a tobacco jar! Isn’t he sly? I love the finely painted details of his feathers and wrinkly feet and the way he spreads his toes into a stable circle around the base. This bird is in my favorite room in the museum, the Arts and Crafts room. The Arts and Crafts movement, begun by William Morris, championed by John Ruskin, and exemplified by the work of Dante Gabriel Rossetti among many other artists, advocated for beauty and craftsmanship in ordinary objects; in particular, the movement spoke out against industrialization and mass production and focused instead on the work of individual woodworkers, printers, painters, and—here—ceramicists. Works from the Arts and Crafts are characterized by their color, beauty, humor, and technical skill.

A Glimpse into Ordinary Life

Edgar Degas is so associated with ballerinas that a humorous online guide to famous painters succinctly says, “If You See a Ballerina, It’s Degas.” In contrast to Degas’s typically graceful, impressionistic, pastel, tutu-ed ballerinas, we have here this earthy, lumpy lady captured in a quotidian moment. I have struck this same pose myself many times to remove a bit of gravel from my shoe. I bet you have too. In this sculpture, Degas takes contrapposto4 to its logical, awkward limit. The ballerina balances on one foot not in a graceful arabesque but instead to pull out a thorn or splinter, or to make sure she didn’t just step in something icky. Her body curves not gently like Michelangelo’s David but instead in a sharp zigzag. Her skin isn’t flawlessly smooth but instead is marked with scratches, breaks, and other imperfections. She is made not of alabaster but of bronze. She is like all of us, and I love her for that.

Speaking the earthy and quotidian, how could I not love this floppy fellow? Most of the time, when dogs appear in paintings, they are pampered lapdogs or elegant hunting dogs. But an anonymous seventeenth-century painter chose to immortalize this humble street dog, who, far from being a fancy purebred, is some indeterminate mishmosh of breeds. The glint in his eyes and his protruding tongue suggest that he wouldn’t be averse to a little treat. He lies on his side instead of curling up, showing us how relaxed he is, a feeling that is reinforced by the horizontal line of his body across the middle of the painting. At the very center of the painting is the glowing white of his soft, clean chest. His paws curve gracefully into a circle, suggesting that he doesn’t feel the need to protect his belly. His muscled haunch and neat fur, rendered in smooth brushstrokes, suggest that he is well-fed. I hope so, anyway!

He reminds me of my own street dog, Lynn, and that’s why he is my very favorite painting in the Ashmolean.

Evidence from the Past

Sometimes when I’m walking through a gallery, an image stops me in my tracks not because it is beautiful but because it testifies to a heartbreaking reality from the past.

I included this little girl right after the street dog on purpose. The wall text tells us she is “a servant or a hard-worked daughter of the house.” Her posture is mostly horizontal like the street dog’s, but unlike the street dog, who seems spunky and cheerful, this poor little girl slumps in exhaustion. There is no glint in her eye as she rests her weary head on her shoulder and warms her dirty bare feet. Holl chose grays and browns for this grim scene; the only spots of color are the rusty marks on the cloths and the hint of pink on the girl’s cheek. The fire must be quite meager, because we can scarcely see its light. The smeary charcoal on the door and back wall suggest that the girl’s work is far from over, and her dirty bare feet reflect the filthy conditions in which she must labor. Saddest of all to me is that she doesn’t even notice the kitten in the corner. Have you ever met a little girl who was too exhausted to notice a kitten? This painting is evidence of the brutal, cruel reality of child labor—worse than the life of a street dog.

Our next little girl comes from the opposite end of the economic ladder.

Sir Joshua Reynolds was the pre-eminent portraitist of eighteenth-century England and a member of Samuel Johnson’s circle. He painted portraits of the richest and most prominent members of English society, including, here, little Penelope, daughter of Sir Brooke Boothby of Ashbourne Hall, Derbyshire, and his wife Susanna Bristowe.

She is such a wistful little miss. You have to wonder what she is looking at off to the side of the frame. Her mom? Or a favorite pet? In contrast to children in typical aristocratic family portraits, who stand stiffly in their confining adult clothing, Penelope sits comfortably in her pouf of a dress, balanced by her pouf of a hat, and her soft natural curls gently frame her face. Only three years old in this painting, Penelope died three years later. She was the Boothbys’ only child, and, devastated by their terrible loss, the couple split up shortly after her death. This portrait of a much-loved and tragically lost child reminds us that this was a time when even the most privileged people were powerless against disease.

A Story with a Happy Ending

Readers may remember that I wrote about John Ruskin a few weeks ago. To recap, we art lovers should be grateful to Ruskin: his keen artistic eye and advocacy are why the greatest painters of his age, including Turner and Rossetti, were able to flourish and create so many works we now enjoy. But Ruskin was ill-suited to the married life, famously recoiling from his new wife, Effie’s, body on their honeymoon. But I have good news for you all! Take a look at this portrait of Ruskin, which was painted by his good friend Sir John Everett Millais on a trip Millais took with the Ruskins.

I get a kick out of how Ruskin is surrounded by all this wild nature, the craggy rocks, and the crashing waves, but he is not looking at any of it. He is staring off into the distance, thinking about higher things. In fact, Millais painted the outdoor scene on the trip and then added in Ruskin, who posed in Millais’s studio, afterwards. I’m reminded of Cecil Vyse from A Room with a View, about whom other characters comment that they can never picture him outdoors but can only imagine him in a room. Anyway, Millais fell in love with Effie on this trip, and she reciprocated his feelings. Because the Ruskins’ marriage was never consummated, it was easy for them to obtain a divorce, and Effie and Sir John married the next summer and lived happily ever after. The Ashmolean waggishly refers to this portrait as “The painting that caused a divorce.”

How about you, readers? Is there something you love even though you are a total amateur? It doesn’t have to be art—it could be music, a sport, cooking, or really anything that you enjoy. Do you feel as though being an amateur hinders your enjoyment, or is your lack of expertise an advantage? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Is it my imagination, or does this bust of Lorenzo de’ Medici look a lot like Tommy Lee Jones? The bust, “perhaps the workshop of Antonio Benintendi,” was “probably based on a life mask (a cast of the face of a living person).” Lorenzo may have ruled Florence during the last half of the fifteenth century and been an important driver of the Renaissance, but when I look at this bust all I can imagine is him saying, in a deadpan Texas twang, “All right, guys, listen up!”

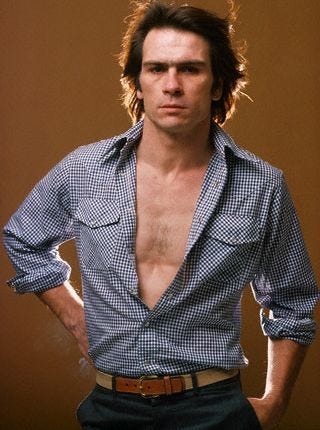

For comparison purposes, here is a totally gratuitous photo of a young Tommy Lee Jones. You’re welcome.

Readers of my post on perverse incentives will recognize that I had not yet internalized my father-in-law’s question, “Why pay twice?”

I apologize in advance for the poor quality of some of these photos—because of the lighting in the galleries, I had trouble avoiding reflections and shadows on the paintings.

I read Fanny Hill (the real title is Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure) for a class on the eighteenth-century novel back in grad school. If anyone tells you that “those were more innocent times back then,” I suggest you refer them to this highly salacious novel. It will open their eyes!

Ha! A term from art! Contrapposto simply means that the figure has his or her weight on one foot, which throws the rest of the body into an elegant curve.

This is a most wonderful article, Mari, and I want you to know how much I enjoyed it. I never really had the opportunity to learn much about art and am getting a bit too old for wandering around galleries now, but you have given me a few pointers for even looking at photos of art works.

On a trip to Columbia in 2017 I was bowled over by the paintings of Botero with all of these huge people and some of them so funny - the apple as a symbol of deliciously enjoyable sin, really made me laugh 😃 I can't help but wonder what Ruskin, so shocked by public hair, would have made of Botero? (I had never heard that story before. It is both funny and really sad at the same time. I was so glad to know that his wife did re-marry.) I also loved the Botero sculptures, particularly one I saw in a park of a Chinese face; it was so huge and yet so gentle and delicate.

The Australian artist, Ben Quilty, has also painted some extraordinary powerful - in my opinion - portraits of soldiers in leisure moments, in Afghanistan. I was again bowled over effect on me of these paintings, which I saw at a gallery in South Australia. Thanks again for your article and all your insightful, interesting contributions to the slow reads we have done.

Since Christmas 2021, Rich and I have gotten into collecting fragrances as a means of experiencing world travel destinations within our home. We've sampled and collected fragrances that smell of grass, greenery, wood, flowers, fruits, nuts, amber, vanilla, chocolate,(synthetic) musks, soil, burning leaves, resins, incense, soaps, and many more scent notes. There are expert "noses" who create fragrances for designer fragrance houses and niche fragrances houses: these are the people who create new fragrances for the extensive fragrance market. We have had so much fun learning from expert noses, and online amateur fragrance collectors. Almost two years in, we've become quite knowledgeable about a collection we enjoy right at home every day! 🦋🧡🦋