Ding ding ding! We have a winner! A couple of weeks ago you voted on what we should read for our summer book club, and “Bartleby the Scrivener,” by Herman Melville, was the top choice. A free version is available here, or you might have a copy knocking around somewhere in your old college textbooks. The story is about forty pages long, so we will have plenty of time to read it before July. I’ll introduce the story on July 5 and offer some questions to think about as we read. Our discussions will be on July 12 and 19. Thanks in advance for participating, and happy reading, everyone! Now, on to this week’s post.

I have loved classical music since early childhood, when I played piano and sang in multiple choruses. I still sing, and my husband and I attend several classical concerts a year. Heck, at this very moment I am listening to a recording of a Schumann piano quintet. But even I have my limits. One year when we lived in Prague, we subscribed to a string quartet concert series. For each of five concerts over the course of eight months, the string quartet would play two quartets, then there would be a long intermission, then they would play two more quartets, we would applaud . . . and then they would play a movement from yet another quartet as an encore. That is a LOT of string quartets! The management clearly wanted us to feel as though we were getting our money’s worth, but as I felt my eyelids becoming heavy or as I squirmed restlessly in my seat, I would catch myself thinking of that old New Yorker cartoon: “Ye gods, will this concert never end?!”

Classical music is having a bit of a moment right now. The music critic Ted Gioia notes that classical music has seen a surprising increase in popularity during the past two years. A few weeks ago, Maureen Dowd waggishly called this growing love of classical music a crescendo and cited as evidence of its powerful impact the woman who enjoyed a recent performance of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony perhaps a bit too much. (As one commenter quipped, “I’ll hear what she’s hearing!”)

But while the Metropolitan Opera, world-famous soloists, and major symphony orchestras almost always sell out their concerts, smaller and less-well-known groups struggle to attract audiences. More often than not, concerts are sparsely attended, or the audience is composed almost exclusively of older people:

Of course, money is a possible explanation for why younger people rarely buy tickets to classical concerts. The opera and the symphony are expensive, after all, and Millennials and Zoomers are already so burdened with student loan payments and rent that is too damn high that they have little to spare, even for the likes of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven. However, the cost of concerts can’t be the whole reason for young people’s reluctance; many organizations offer very low student and young-adult ticket prices or free dress rehearsal tickets. Besides, rock and pop fans regularly shell out enormous sums for their favorite acts—case in point, the hundreds or even thousands of dollars fans are willing to pay to see Taylor Swift this year. So it’s not just the cost keeping younger fans away from classical music.

The Real Reason People Don’t Go to Classical Music Concerts

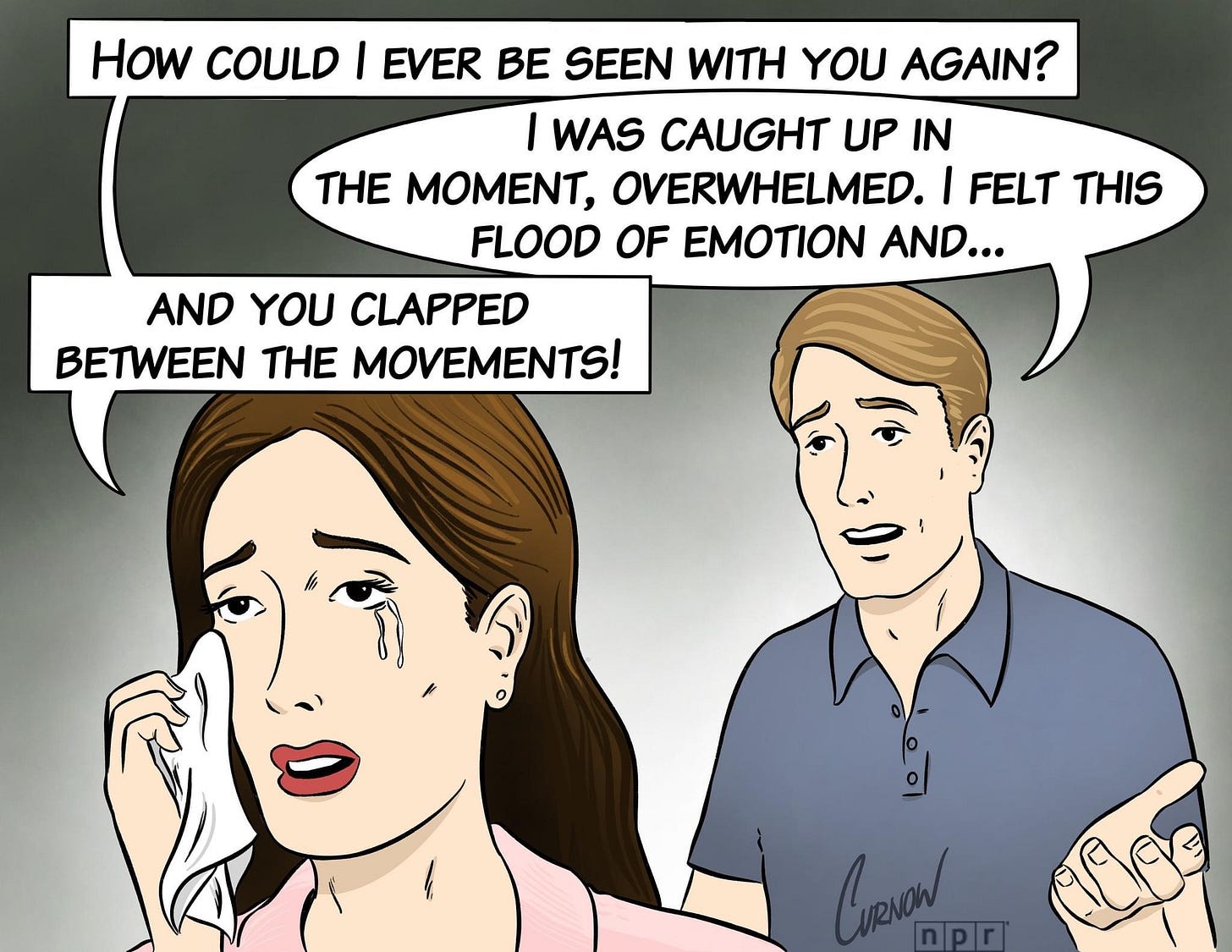

We don’t know when to clap. I’m serious! Between movements, there is that terrible, awkward pause, and then one intrepid soul might burst out in applause, only to be shushed and forced to retreat, abashed, from the censorious stares of others in the audience. Clapping between movements outs us very publicly as classical music newbies or ignoramuses.

In spite of my musical education and frequent concert attendance, I still don’t always know when to clap. This is why I always have the program open on my lap—to keep track of the movements so I know when the piece is over. In theory the conductor should cue the audience by dropping his or her arms and heaving a satisfied sigh, but many conductors’ final gestures are ambiguous or too understated to clue us in. “Is the piece over? Do we clap now?” the audience wonders. Which leads to another terrible, awkward pause. While we don’t want to risk embarrassment by being the first to clap, we do want to give the musicians their well-deserved applause (or, if we didn’t enjoy the concert, at least to be polite). I have been to a number of concerts where no one clapped at all,1 and finally the musicians just sheepishly filed off stage, only to be recalled to take their bows once their departure made it clear that the show was over.

The saddest thing about this uptight rule is that musicians are human and enjoy spontaneous bursts of enthusiasm the same as everyone else. Last month I went to a chamber concert that had several kids in the audience. They were refreshingly uncowed by the clapping etiquette and burst out with cheers every time the music stopped. The musicians loved it, based on the wide smiles they bestowed on the kids. At the opera people clap and cheer after arias, and I think we need to bring this generous appreciation to other kinds of classical music too. In fact it used to be the norm to clap between movements of symphonies and chamber pieces. (I recommend this article, which tells the history of why the practice changed.) So let us clap unashamedly when we are so moved!

Another approach would be for the conductor and other musicians to not be so dang subtle. Many years ago, I experienced what a relief it is for audiences when the performer makes the rules clear. A friend and I attended an afternoon recital by the great soprano Leontyne Price, and the audience was, heartwarmingly, filled with Black grandparents taking their little grandchildren to see the great diva. Price was clearly aware that the children might not be familiar with clapping etiquette, because whenever the audience clapped at an inappropriate time, she made a quick gesture that cut them off. And when it was the proper time to clap, she took a huge, obvious bow—and was rewarded with our wild ovations. I have written before about ideas for making classical concerts easier and more pleasant for the uninitiated, but a great start would be for musicians to tell us when to clap.

Sitzfleisch and Historical Accuracy

Sitzfleisch is a German word that translates as “sitting meat” (i.e. our tushies) and refers to our ability to persist with dull tasks. It’s the patience to endure a long slog uncomplainingly. The term has been used to describe people who can sit still and pay attention through protracted and soporific classical concerts. While I agree with Pascal that “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone,” I also wonder why we assume that classical concerts must make this demand on us—in other words, Why must we pay rapt, silent, motionless attention to concerts that are often long and sometimes boring?

Yes, classical concerts can be boring. If you don’t believe me, I invite you to try this test at your next concert: How much rustling and coughing do you hear? Critics will blame and scold audiences for this behavior, but I think the fault lies with the concert itself, be it its length or its choice of pieces. When we are absorbed in the music, we are able to ignore—or forget entirely—our petty discomforts, but when we are bored, a tickle in the throat or an aching back nag and rankle, and so we cough and rustle. At one of the aforementioned marathon string quartet concerts, the audience made their boredom clear when they let loose a tremendous cacophony of coughing between movements. (“How are these people even ambulatory?” I wondered.) And then one of the violinists started coughing too—and then we all laughed, including the musicians. But perhaps a shorter concert would have placed more manageable demands on our attention and forestalled the coughing in the first place.

Many musical groups strive for historically accurate performances, using period instruments, setting A below 440,2 and—frustratingly for us mezzos—giving the alto parts to men. But it is ahistoric to require that concert audiences sit as silently and motionless as though they were hearing a Puritan sermon. Modern audiences ought to be allowed to experience music the same way we have enjoyed music throughout human history. Before the era of the large symphony orchestra and concert hall, audiences didn’t sit passively and reverently during concerts. They heard music at parties and outdoor festivals. They strolled around, ate, drank, gossiped, peered at each other through opera glasses, and occasionally dipped in and out of the music to hear favorite passages. Most of all they danced, oblivious to the music and focused on each other, as Mr. Darcy3 and Elizabeth do here:

Our society has a strange belief that the way we show respect at public gatherings is not only to sit still and silent for protracted periods of time, but, worse, to do so in expensive, constricting clothing. This expectation places a barrier against the many people who might otherwise enjoy a classical concert but can’t afford formal clothing or simply dislike the way it pinches, chafes, and binds. Classical music would attract a wider audience if it were acceptable to dress comfortably at concerts.

When we lived in Prague, a man wrote a grumpy letter to the editor complaining about “foreigners in sweaters” taking up seats at classical concerts, seats that could otherwise go to Czechs in suits and dresses, apparently. The day after the letter was published, my husband and I had concert tickets. It was winter and freezing cold. Yes, I wore a sweater, and also my hiking boots, both of which served me in good stead as I navigated the icy steps. I’ll go further: If there is one belief that unites us across the political spectrum, it’s that we like comfy shoes, as we learned from a recent New York Times article about the “dress sneakers” worn by Representatives Hakeem Jeffries and Kevin McCarthy and Senator Mitch McConnell to a meeting with President Biden. If no one cares about comfy shoes in the Oval Office,4 surely we ought not to care if they are worn in our concert halls too.

Finally, It Helps to Include a Dog

I am not speaking metaphorically. I mean an actual dog. A few years ago, I was in the audience waiting for a concert to begin in the Rudolfinum, an elegant, neo-Renaissance hall in Prague, when we got a delightful surprise: A pretty springer spaniel darted onstage, raced around, and darted off. Then, just when we were asking ourselves if we had been imagining things, he raced onstage again, capered, wagged his tail at us, and scampered off. Yes, we all applauded him! Even in such a formal and highbrow venue, everyone loves a perky dog.

Or here’s another story: Two of my sisters-in-law, Mel and Robin, arranged a wonderful house concert a few years ago. They hired a classical guitarist through a service, and Mel and her husband, Ross, hosted the concert in their home for a couple dozen people. While we sipped wine and lounged on comfortable sofas, the guitarist performed several beautiful pieces. Before each piece, he told us a bit about the composers and pieces. We took a break for refreshments and had a chance to talk with him about his training and experiences, and then the concert resumed for another half hour or so. A highlight of the evening for many of us was when Ross and Mel’s dog, Penny, who is part beagle, attempted to sing along. We all laughed (including the guitarist), gave Penny a few pets, and then shooed her out.

My point is that Mel and Robin’s house concert was closer to the way music has been performed and enjoyed for nearly all of human history than is the overly formal, worshipful, and uncomfortable regime of sitzfleisch in our concert halls. Music engages us, moves us, and delights us all on its own. There is no need for us to be required to sit perfectly still and quiet for hours, drifting in and out of boredom in our most constricting clothes. Music ought to be a part of the bounty of regular life—which includes applauding children; sipping, lounging, flirting, and dancing partygoers; and, yes, capering and howling dogs.

How about you, readers? What was the most memorable concert you’ve ever attended or performed in? And what are your ideas for how to attract more people to classical concerts? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Speaking of Leontyne Price, below is her flawless rendition of “Vissi d’Arte.” Price’s voice reminds me of Joseph Brodsky’s response when he was on trial for “social parasitism,” and the judge asked him where his poetry came from. He replied, “I think it is . . . from God.” Even if you think you don’t like classical music in general or opera in particular, the ravishing beauty and sensitive intelligence of Price’s performance will make a convert of you.

One time I was on the other side of this embarrassing scenario. My choir in Chicago performed a concert of Rachmaninoff’s Vespers, which is a series of meditative, a cappella choral pieces. There was no grand finale or crescendo à la Beethoven to tell the audience we were nearing the end. Even worse, we were in the choir loft, so no one could see us. When we finished, there was this terrible silence for like five minutes, and finally our director hung over the rail of the choir loft and waved at the audience. Ugh. So awkward!

I don’t have perfect pitch, but my ear is good enough that I find the Baroque pitching quite noticeable. Interestingly, A is often set higher than 440 for opera performances. If any readers know why this is, I would love it if you shared the answer in the comments!

Fellow Succession fans: Isn’t it nice to see Matthew Macfadyen playing someone who isn’t a craven bounder? Doesn’t he smolder?

Apart from a few fussy fashionistas, that is. The Times article is fun reading, because it shows that people can get quite het up about something quite trivial.

Hey Mari--Wasn't it me who saw Leontyne Price with you? I will never forget her encore, where she sang "Summertime." She changed how I hear that song and somehow captured the feeling of summer in her performance.

Onto your real question, though. I agree with you about wishing classical concerts were less stuffy. We recently attended a chamber music concert where a friend was performing. The music was lovely. But as usual, I chafed against what I find to be the strange formality of the stage etiquette: the performers all leave stage almost as soon as they are done, and come and go if the applause continues. Then they come out again to play the next piece. Why all so uptight? Even if the music stands have to be rearranged because there's a new configuration of players, as happened at that concert, surely it can be made to feel less ponderous, more energetic. It's as if we all have to be staid and inert and only the music can have spirit, as if our appreciation can only be intellectual. Bring on the dogs, sweaters, and informality. Classical music can be fun, and personal, as you say.

Maybe I’ve told this story before, but I saw Yo Yo Ma perform with the Chicago Symphony once, debuting a new concerto by a composer who was also conducting. I remember being completely enraptured by the music, along with the rest of the audience - the applause between movements was immediate and lasted minutes. What I remember most, though, is that during the final standing ovation Ma put down his cello, leaped up, and ran to embrace the composer. They stood there holding each other tightly while the audience hollered.