Welcome back to the Happy Wanderer Summer Book Club! If you’re just joining us, you can find last week’s post, including a plot summary, brief bio of Melville, glossary, and our discussion, here. I’m looking forward to our continuing conversation this week! By the way, did you keep count of all the “I would prefer not to”s? See this footnote1 for my count.

Were you surprised to discover how funny the story is? (Before it becomes tragic, that is.) The Narrator’s office is totally dysfunctional, what with the drunken Turkey and the choleric Nippers and his eternal battle with his desk and his shady side-businesses. I also laughed at how the entire office starts unconsciously saying “prefer” after Bartleby arrives.2 Or think of how, near the end, the Narrator keeps suggesting wildly inappropriate jobs for Bartleby (a bartender! or a young man’s traveling companion! can even you imagine?). And of course Bartleby rejects each one—while insisting that he is “not particular.”3

The story also contains a mystery: How do we account for Bartleby’s behavior and the Narrator’s very strange “tame compliance” with it? What message or lesson might the story have for us readers, even if we (hopefully) don’t have a Bartleby perplexing us in our own lives?

Two Possible Solutions to the Mystery

One explanation is biographical: Melville’s masterpiece Moby-Dick came out in 1851—two years before Bartleby was published—and was ignored at best and repudiated at worst by critics and the general public. Some modern critics think that Melville expressed his grief and anger over the rejection of his great work through Bartleby’s depression and his refusal to do the routine, copycat writing that the business world demanded of him.

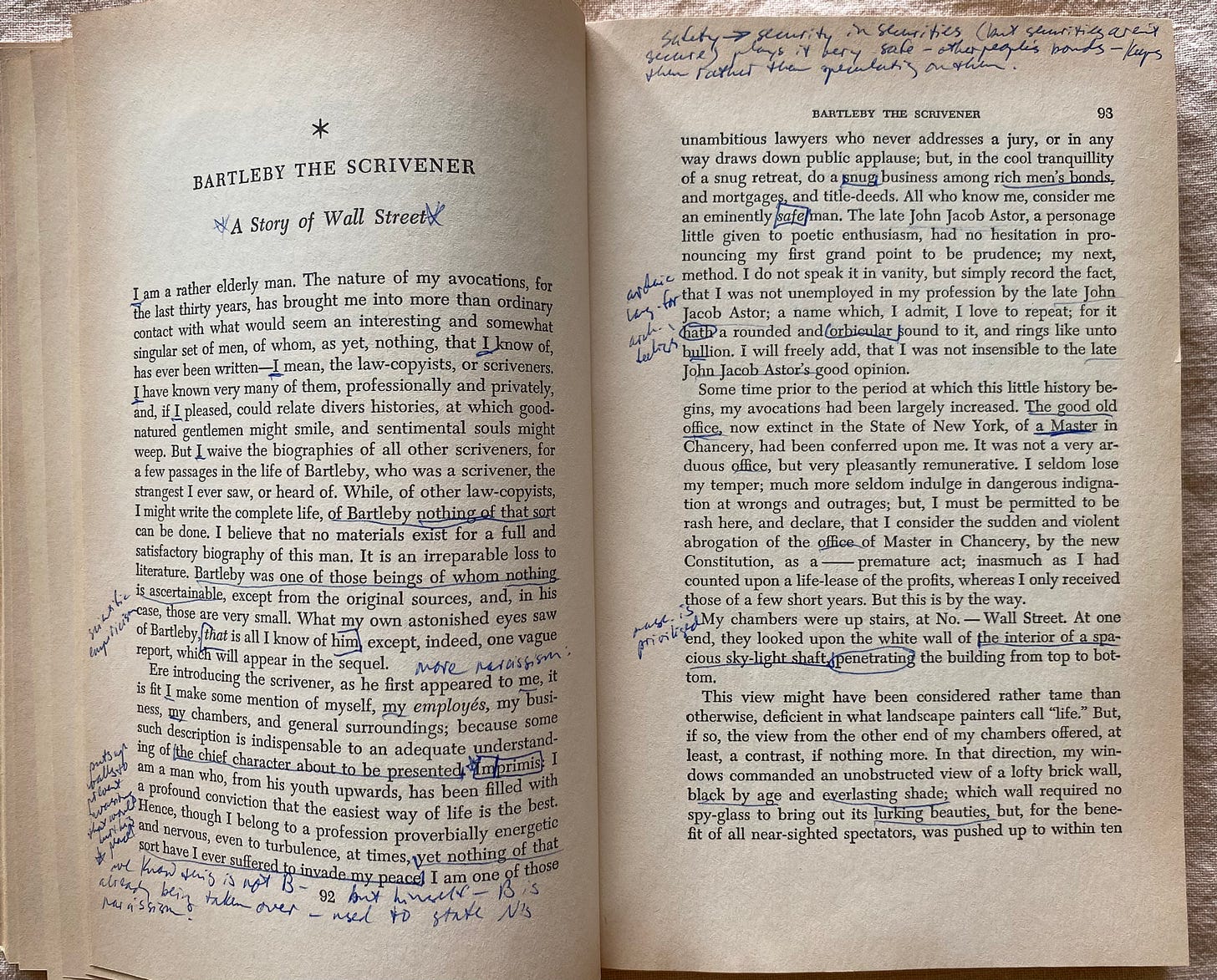

When I was in college, I had a wonderful professor, Bill Veeder, who offered a fascinating psychoanalytic close-reading of the story. Veeder cited textual evidence to argue that the Narrator responds so oddly to Bartleby because he is sexually attracted to him at first and eventually falls in love with him. The setting is full of phallic imagery: Skyscrapers “thrust” into the sky and airshafts “penetrate” them, and the Narrator refers to buildings as “erections.” When Bartleby resists the Narrator’s requests, the Narrator says he was “unmanned.” The Narrator chooses sexually coded words to describe Bartleby’s clothing—his “strangely tattered déshabillé”—when he discovers that Bartleby is living in the office. It is clear that the Narrator’s colleagues suspect that the Narrator is keeping a male prostitute; the Narrator is worried about a “whisper of wonder … running round, having reference to the strange creature I kept at my office.” (“Creature” was an insulting term for prostitutes and mistresses at that time.)

There are literary and biographical justifications for this reading. Many readers have noted the homoeroticism in Moby-Dick—how Ishmael and Queequeg share a marital bed, for example, or how after the sailors catch a sperm whale, they squeeze clumps of the sperm and rub it on each other. While Melville was writing Moby-Dick in 1850, he met Nathaniel Hawthorne, and a passionate friendship developed between the two men. They visited each other frequently, and the surviving letters from Melville to Hawthorne reveal his intense love for the other writer. For example, one letter from 1851, which you can read about here, declares that

Your heart beat in my ribs and mine in yours, and both in God’s … It is a strange feeling—no hopefulness is in it, no despair. Content—that is it; and irresponsibility; but without licentious inclination. I speak now of my profoundest sense of being, not of an incidental feeling.

Whence come you, Hawthorne? By what right do you drink from my flagon of life? And when I put it to my lips—lo, they are yours and not mine. I feel that the Godhead is broken up like the bread at the Supper, and that we are the pieces.

Hawthorne was apparently uncomfortable with this intensity, because shortly after receiving this letter he distanced himself from Melville. Melville lamented the loss of the friendship for the remainder of his life; one of Melville’s final poems is about his sadness at being “estranged” from Hawthorne after having “loved him.” This passion, and its cooling off, happened while Melville was writing “Bartleby.” It is easy to imagine that Melville was thinking of his own fruitless pursuit of Hawthorne when he wrote about the Narrator’s initial preoccupation with Bartleby, his desire to have Bartleby come live with him, and his distress when Bartleby rejects his offer.

“Business Hurried Me”

“Bartleby” also readily lends itself to a Marxist, pro-labor interpretation. The story is set on Wall Street, which Melville depicts not as bustling and productive, but as an oppressive prison:

My windows commanded an unobstructed view of a lofty brick wall, black by age and everlasting shade; which wall required no spy-glass to bring out its lurking beauties, but, for the benefit of all near-sighted spectators, was pushed up to within ten feet of my window panes. … The interval between this wall and mine not a little resembled a huge square cistern.

Melville alludes to formerly grand empires that have fallen into decay and desolation—Petra, Carthage, and the ruined realms of the “kings and counselors” in the verse from Job that the Narrator quotes at the end—suggesting that Wall Street is vulnerable too. He also mentions two injustices in the world of finance: the Narrator’s sinecure obtained through patronage and the losses on the stock market after Monroe Edwards’s fraud. And, pace claims that pure capitalism is the most rational and efficient way to run the world, no one would take the Narrator’s office as a model for how to run anything.

In fact the workers in the Narrator’s office suffer from and struggle against alienation: Their work is tedious, repetitive, and meaningless, and they toil not for their own profit, or even that of the Narrator, but instead for “rich men” and their “bonds.” Turkey is a barely functioning alcoholic, and Nippers runs his side business out of the office in order to make money and stick it to the man. Even Ginger Nut, who, as an apprentice, is in theory supposed to be receiving training in the law so that he can advance in society, actually spends his time as an underpaid “errand-boy, cleaner and sweeper.”

Bartleby is the most alienated of all, but he rebels too, at least at first. He refuses to pretend that he enjoys his job, to the Narrator’s chagrin: “I should have been quite delighted with his application, had he been cheerfully industrious. But he wrote on silently, palely, mechanically.” Bartleby also refuses to do any work that is not explicitly part of his job; he is a “scrivener,” and scrivening, narrowly defined, means copying documents only, and not comparing and proofreading them, running errands, or any of the other tasks the Narrator and other lawyers ask him to do. Bartleby’s “work-to-rule” strike aggravates the Narrator, who understands it as a “rebellion.”4

Bartleby’s despair, and his strike, eventually become total, and he refuses to work altogether. When Bartleby falls into his “dead-wall reveries,” the Narrator asks what troubles him. “Do you not see the reason for yourself?” Bartleby replies, indicating the black wall outside his window. The Narrator, at this point still in thrall to the dehumanizing world of business, rationalizes to himself that Bartleby suffers not from alienation and depression but rather from poor eyesight. Bartleby is a dead letter, and the Narrator can’t yet read his message.

From “An Eminently Safe Man” to “Ah, Bartleby! Ah, Humanity!”

Although these biographical, psychoanalytic, and Marxist readings are interesting, I believe that the most meaningful and useful way to understand the story is as a spiritual and moral lesson that Melville intended for his readers. It might seem odd to claim that there is an edifying message in this story: If we consider Bartleby’s fate to be the point of the story, all we are left with is mental illness, despair, and death. There was never any hope for Bartleby—not without putting him in a time machine and sending him to Michael Pollan to microdose psychedelics, that is. However, in spite of the story’s title, this is not the tragedy of Bartleby, but rather a hopeful story of the Narrator’s growth and change because of Bartleby. Or, as Brandon put it last week, “the central dilemma that struck me in the story is, ‘how far do we extend decency and compassion to those who fall outside the norms of society?’”

At the beginning of the story, the Narrator is a laughable character—a weak, passive, social climber who puts the “safe” and “easiest way” ahead of authentic interactions with other people. Melville makes the Narrator’s narcissism clear from the first two paragraphs, ostensibly about Bartleby, in which the Narrator repeats “I,” “me,” and “my” thirty-three times, and “Bartleby” only four times. The Narrator at first quite explicitly refuses to look at Bartleby, placing him behind a screen “which might entirely isolate Bartleby from my sight” and demanding that Bartleby take a document without even doing him the courtesy of looking him in the eye:

I abruptly called to Bartleby. In my haste and natural expectancy of instant compliance, I sat with my head bent over the original on my desk, and my right hand sideways, and somewhat nervously extended with the copy, so that, immediately upon emerging from his retreat, Bartleby might snatch it and proceed to business without the least delay.

In Kantian terms, the business world and the Narrator use people as a means to an end, rather than as ends in themselves. The Narrator’s dehumanizing “expectancy of instant compliance” is what Bartleby refuses when he says, for the first time in the story, “I would prefer not to.”

But through Bartleby, the Narrator learns compassion. After even a single “I would prefer not to,” we might expect the Narrator to become angry and to fire Bartleby on the spot. (Rick had a creative idea last week for how the Narrator could have handled the situation: “Wouldn’t a lawyer be able to think of some clever trick to force Bartleby into some decision? ‘Bartleby, it would be most helpful for us if you would stand there all day while we hang our jackets on you.’”)5 Instead the Narrator accommodates, accepts, and even begins to pity Bartleby: “Immediately then the thought came sweeping across me, what miserable friendlessness and loneliness are here revealed! His poverty is great; but his solitude, how horrible!”

While the Narrator’s compassion is initially motivated by self-interest—“Here I can cheaply purchase a delicious self-approval. To befriend Bartleby; to humor him in his strange willfulness, will cost me little or nothing, while I lay up in my soul what will eventually prove a sweet morsel for my conscience”—by the end of the story he cares deeply about Bartleby and is willing to spend money and to sacrifice his own reputation to save him. No longer “an eminently safe man,” he takes a risk and makes the extraordinary offer to have Bartleby come live with him, an idea that “had not been wholly unindulged before.” And even though he is hurt by Bartleby’s rejection, he nonetheless visits Bartleby in the Tombs (which he had always made a point of avoiding in the past) and attempts to pay for Bartleby’s care.

The Narrator fails to rescue Bartleby; he tries his best, but his best is inadequate to the task. And yet, imperfect as the Narrator is, he has learned to see Bartleby as a fellow human worthy of love and care. “Bartleby, the Scrivener” challenges us in turn to do our best—to be compassionate and charitable, to see our common humanity, to understand that we are all “sons of Adam.” Our efforts to help the suffering people we encounter may be as hopeless as those of the Narrator. They may come too late. All we can do is try, and if enough of us do that, we can begin to repair the world. We may not be able to save the Bartlebys in our lives, but when we extend kindness, understanding, and generosity to our fellow humans, we will save our own souls.

How about you, readers? What do you think of these various interpretations? What is your own explanation of the story? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

In the video below, the philosopher Slavoj Žižek discusses the “everyday ideology” of “I would prefer not to.” He and the interviewer both mention a number of jokes that take the same form, in which nothing happens, but a friendly connection between strangers is made nonetheless. Or, in Žižek’s words, “Although the result was zero, the link was established—the link of kindness. The signal was ‘we are polite to each other, we like each other.’”

A woman goes into a coffee shop and asks for coffee without cream. The barista says, “We don’t have cream, so is it ok if I give you coffee without milk?”

Here’s a version of the joke from Žižek’s childhood in communist Slovenia:

A man walks into a shop and asks, “Is this the store that is out of butter?” The clerk replies, “No, this is the shop that is out of oil. The shop that is out of butter is across the street.”

Or there’s this classic version:

A man walks a woman home after their date, and she invites him up for coffee. “Oh, I don’t drink coffee,” says the man. “That’s ok, I don’t either,” says the woman.

I counted twenty-four. What did you get, readers? Interestingly, Bartleby’s penultimate “I would prefer not to” is directed at the Narrator’s invitation to Bartleby to come live with him, and the final example is Bartleby’s refusal of food in the Tombs.

This phenomenon reminds me of an experiment my friend Rick (the same Rick who is quoted later in this post) tried when he worked in a restaurant in college. He would seed (infest?) the restaurant with an earworm every day: He’d arrive in the morning humming a catchy tune, and then for the remainder of the day he’d listen to the tune traveling among the staff. By the end of the day, everyone would be unconsciously humming the tune.

All quotations are taken from the edition I used in college, Herman Melville: Selected Tales and Poems, ed. Richard Chase (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1950). It is a sign of how much I love “Bartleby” that I have managed to hang on to this book through the decades—and through two cross-country and two international moves.

This article makes the case that Bartleby’s tactics are quite common in today’s work world.

I suspect that Bartleby would have been content to just stand there with everyone’s jackets hanging off him, though. A win-win!

These are wonderful analyses, Mari — thanks so much for putting all this together. It was a delight to read.

I do think it’s ultimately a philosophical story — a story about how to live — albeit perhaps one without a clear resolution. The narrator says on the first page that he has always believed that the easiest way of life is the best. Melville being as careful as any Save-the-Cat screenwriter in his planting of story clues, I think that philosophical position is the one that Bartleby‘a presence challenges.

The narrator has an easy life. He isn’t idle, but he has maneuvered himself into a position where he is comfortable and secure. He is not greedy or stingy — a comfortable life is enough for him, and unlike, say, Scrooge, he uses his means to make others comfortable, too, although they are not especially deserving. The narrator is routinely generous and forbearing with his clerks (his offer of a coat to Turkey is partly self-interested, but partly kind, too), and the scene where he tries (and fails) to convince Turkey to go to half-days really prefigures his later struggles with Bartleby.

The narrator, then, is a rationalist. He attempts to get the most ease and comfort for himself and those around him for the least amount of work. As long as they all obey the rules (there are multiple references to the narrator’s expectation of obedience and deference from the clerks— and he himself is comically deferential to and admiring of his betters, like John Jacob Astor), they can all have plenty. (This is why he is so angry about the amendment to the New York Constitution that eliminates the Master of Chancery position — society has changed the rules on him midstream, which strikes him as unfair and not in keeping with the rule of easygoing patronage that he strives to live by.)

Bartleby, on the other hand, is completely unsatisfied with this life. There is nothing in it for him. The dead letter office, full of the evidence of pointless life-effort that accomplished nothing and reached no one, perhaps reflects his view of the narrator’s easy life.

At first Bartleby rebels in a small way, by trying to do even LESS than the rather small amount that is demanded of him. As he goes further along, his actions become a terrible parody of the narrator’s own search for an easy life. How much can he take, for how little effort? Can he refuse to do the work the other clerks do? Can he essentially steal a man’s office? At each stage, he takes something from someone else — until finally he becomes the responsibility of the state, which is to say, his entire living becomes dependent on other people and he does no labor at all. But he doesn’t frame it that way for himself; for him, each decision is simply an expression of a negative preference. He perceives himself as simply doing less and less, while in reality he is taking more and more. But in the end, having studiously taken from everyone possible through his nihilistic inaction, there is no one left to take from except himself. And so his final theft by inaction, his final and ultimate act of ease-seeking, is to take his own life from himself.

Bartleby, to me, tests the narrator’s rational point of view by pushing it to an absurd extreme. Yes, the narrator too gets his living from the taxes of the public, but he provides at least SOME service in return. There are references to him appearing in court and hearing cases, so he does SOMETHING, even if it is an easy sinecure. But Bartleby pushes the logic of the easy life to its absolute end — and discovers, there, the end of life itself. The narrator wisely doesn’t follow him there. But he is disturbed by Bartleby nonetheless, because he sees in him a profound, almost Nietzschean challenge to his own life of more moderate leisure-seeking. The narrator believes there is a way for us all to live easily through an orderly social system of patronage and charitable indulgence. Bartleby calls into question whether that is how a human being can really live.

Matt Taibbi & Walter Kirn have a weekly short story discussion at Racket News on their podcast, "America This Week."

Thanks to Mari I'll look super smart. Tomorrow's story (episode 49) is “Bartleby the Scrivener.”

https://www.racket.news/s/america-this-week