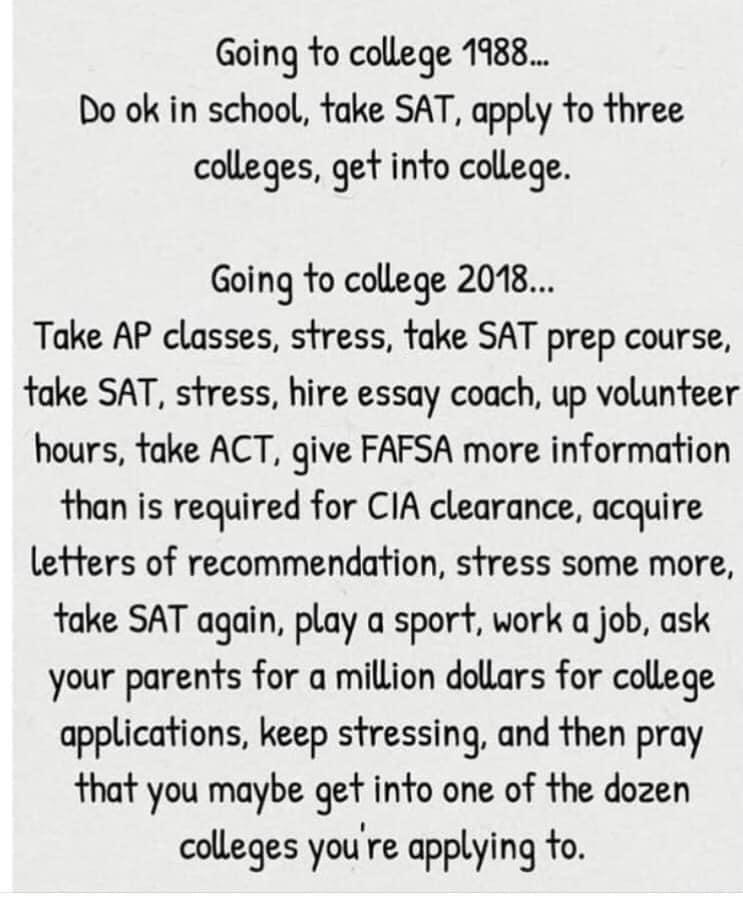

This week, across the US, high school seniors who applied to college early decision are anxiously awaiting their results. Other students are laboring away at the monumental task of completing their applications. Older readers many not realize just how insanely elaborate college applications have become. To wit, this meme:

The reality is in fact worse. Many students write not one but several essays for each application (elite college1 applications offer multiple additional essay questions that purport to be optional, but woe betide the student who skips them); they assemble a portfolio of artwork; and they produce videos that highlight achievements in sports, music, or theater. I don’t know of anyone who likes the way the admissions system works these days, apart from private college admissions counselors, who charge on average $200 per hour.

The Problem: Elite College Admissions Is Unfair and Rife with Perverse Incentives

Elite college admissions is not fair, and everyone know it. Legacy applicants are among the most privileged students in the country, and yet they receive a huge advantage in admissions. The largest admissions advantage goes to recruited athletes—as much as four times the admissions rate of similarly qualified non-athletes—even though recruited athletes tend to be richer than the average applicant (their families must pay for expensive sports like travel soccer, gymnastics, lacrosse, or crew, for example, and top athletes often need a stay-at-home mom or nanny to schlep them around).

Other lesser-known advantages available to affluent kids include

applying early decision (admissions decisions are binding even though applicants don’t know how much financial aid they will get, which is a big deterrent for low-income kids);

being the child of a faculty member;

having their parents buy them a spot with a hefty donation;

taking standardized tests multiple times but only reporting the highest scores (colleges are complicit in this: many elite colleges “superscore” applicants’ SATs and ACTs, which improves the colleges’ US News rankings but only helps kids who have the time and money to take the tests multiple times);

being a private school student and thus having access to better letters of recommendation;2

having a private coach to help with interviews and essays;

and having more time for extracurriculars because they don’t have to work at paying jobs or take care of younger siblings.

Even worse than the injustices, the current admissions system incentivizes psychologically unhealthy behaviors. In the hope that their child will become a recruited athlete, families sacrifice their weekends, summers, and holidays to the demands of travel sports. High school students frenetically join as many activities as possible, whether they’re interested or not, to build their college resumes. Paid consultants help kids craft a persona for admissions committees, encouraging kids to market themselves as a product. Students, conscious that a single mistake or low grade could keep them out of a top college, are reluctant to take academic and personal risks.

The current system is a perverse incentive for the colleges too: in order to raise their US News and World Report ranking, colleges make their rejection rates as high as possible by soliciting applications from kids who have no realistic chance at all. They must hire more admissions officials first to recruit and then to process more applicants. The colleges then pass along the costs of these additional administrators to their students in the form of yet higher tuition. It’s a vicious circle.

A Couple of Caveats

In spite of the injustices listed above, we should note that elite college admissions is a relatively minor problem: we’re only talking about a hundred elite colleges and the half million3 or so kids who apply to them each year (plus their stressed-out families, of course). Most colleges admit more than half their applicants, and families can save time, stress, and money through the simple expedient of choosing an excellent public university or community college.

And yes, I know that this lottery idea could never happen—or at least it’s highly unlikely. That’s why this is a Modest Proposal. But as with Swift’s brilliantly scathing essay, sometimes when you propose something that sounds extreme, you provoke readers to confront problems and think about solutions more creatively. I’m not the only one who advocates lottery admissions: the philosopher Michael Sandel, in his recent book, The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good, proposes that Harvard admit one freshman class by lottery and then compare the lottery-admitted class to traditional classes.

In spite of these caveats, I think it’s worth talking about the problem and proposing solutions. Maybe “only” half a million kids plus their parents are directly affected every year, but the climate of competition and stress in our high schools affects millions more young people. Perhaps high-school seniors who hear about this lottery idea will think to themselves, “You know what, that’s exactly right! Admissions is arbitrary, and I don’t have to feel bad about myself if I don’t get into my top choice.” Others might think, “This current system is not working for me, and I don’t want to waste my time and money on it.”

Lest you all think I sound like John Cleese pretending to be a famous paleontologist with a theory about the Brontosaurus and then hemming and hawing and throat-clearing for an inordinate amount of time, I will finally turn to how my idea would work.

My Solution: An Admissions Lottery

Our country benefits when academically talented kids of every race and class, not just the privileged, have access to excellent college educations. However, we should remember that we need more than academic talent for our country to prosper. Personal traits such as cooperation, persistence, taking responsibility in the family and at work, and caring for other people are crucial too. So our system should reward both academic ability and good character.

And wouldn’t it be great for kids to just be kids a bit longer, instead of having to start preparing for applications in their early teens? Wouldn’t it be wonderful if high school kids could explore subjects and activities that truly interested them instead of building a resume? Don’t we want kids to try things out and sometimes fail? Or, heck, even just have a few lazy days with no activities every now and then? My modest proposal avoids perverse incentives and instead encourages the traits we actually want for our kids and for our future.

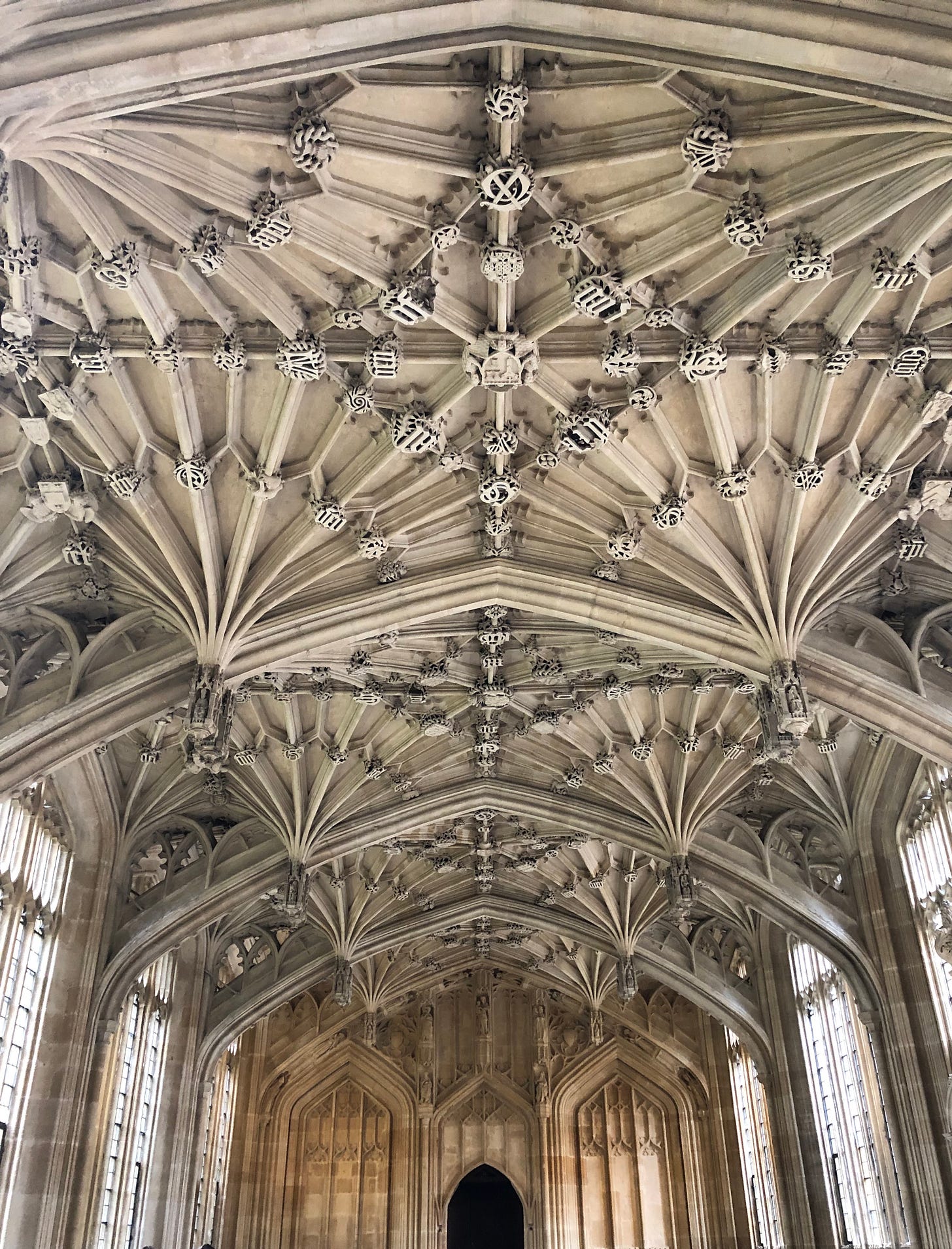

First, and I stole this idea from the UK, we should cap the number of selective colleges kids apply to. (There would be no limit on applications to non-selective colleges, or “safety schools.”) In the UK, the maximum is five colleges. This limit gives kids options but also encourages them to focus on what they really want in a college rather than just desperately applying everywhere. A cap also means that there will be fewer applicants to compete with at each college. Finally, a cap discourages colleges from soliciting applicants purely to boost their statistics.

Next, in Europe, college-bound students take exams at the end of their senior year, and European colleges publish the minimum exam score that students need in order to apply. The result is that students don’t waste their time applying somewhere they will have no shot. I’m reminded of Dave Barry’s amusing and astute observation that in the US no one will tell you what the real speed limit is. (The real speed limit is the speed at which you will get a ticket, which may or may not have anything to do with the posted limit.) Similarly, in the US, no one will tell you what grades and test scores you actually need to have good odds of getting in to a given college. So in my ideal system, the most selective colleges would state publicly the minimum GPA and SAT or ACT scores4 students would need in order to apply.

I can imagine additional requirements for some specific programs: top STEM programs may want to replace the SAT or ACT with their own exam (every department at Oxford and Cambridge administers its own specialized exam to all applicants, for example); conservatories such as Julliard or Peabody would likely still want applicants to audition; and art programs such as those at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago or Cal Arts would likely still require a portfolio. But students who haven’t yet decided on a major, or who don’t plan to major in STEM or the fine arts, would not have to supply these additional items just to be admitted to college.

Then, all applicants who meet the grade and exam criteria would get a lottery ticket at each of their five chosen colleges. Because we want to encourage not only raw academic talent but also the personal skills I discussed above, students could obtain additional lottery tickets for the following items. For each of these proposed additional tickets, a school counselor could confirm eligibility, or the student could provide the evidence.

Taking the most challenging program their high school offers. Kids would be rewarded for challenging themselves but not punished if their schools have limited5 course offerings.

Overcoming obstacles and adding new perspectives. This category would include race, sexual orientation, religion, social class, disability, neurodiversity, serious illness, and similar differences and challenges. We would have to be careful that these are legitimate obstacles, though—I’m reminded of the freshman at Princeton who argued in an op-ed that he was oppressed because his grandparents were Holocaust survivors. You only get credit for overcoming your own obstacles!

Doing extracurricular activities. This would include not only sports, music, drama, school government, and other clubs, but also holding down a job or caring for younger siblings or older family members. Note that athletes would get just one ticket, and no special advantages beyond that. Sports teaches teamwork, leadership, and persistence, to be sure, but I don’t see why sports should be considered more worthwhile than any other activity.

Making a true, long-lasting commitment to community service. To receive this ticket, students would need to demonstrate that they had made a significant, enduring commitment to service work and not just volunteered a few hours here and there.

Achieving something truly extraordinary, for example placing at or near the top at the Intel Science Fair, performing in the arts at the professional level, being a chess grand master, medaling at the Junior Olympics, or inventing something that makes the world a better place (check out these kids’ inventions, including a fast-charging battery, a method to clean up the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, and a simple mine detector).

And finally, the application would contain nothing else. No letters of recommendation, no essay, no portfolio, no videos, no interviews, no multi-million-dollar payoffs, and no secret calls between counselors and college Deans of Admissions.

Of course, lotteries aren’t perfect, and some kids might not get their ticket drawn at any college during the first round. So after the lottery, colleges could follow the UK system and release available places to qualified kids who didn’t get offers anywhere else. Or the kids could attend a less-selective (and less-expensive) public university—and do very well there.

The Benefits

A lottery makes explicit the secret of college admissions: much of the decisions come down to luck. Why not just admit it? If we were to acknowledge the role of luck in admissions, we would not only help kids feel better about themselves, but we would also decrease the incentive to apply to colleges for reasons of social status. A second benefit is that a lottery system would lead to true diversity. Right now elite colleges, commendably, have diversity of race, religion, national origin, and sexual orientation, but very little economic diversity, to say nothing of diversity of age, physical or mental disability, etc. Third, admissions by lottery would give kids (and their families) their lives back, and would also free kids to, in Beckett’s words: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” Finally, my lottery system is frugal: it would save kids time, save parents money—both during the application process and in the form of tuition—save everyone a lot of stress, and return colleges’ focus from marketing to education. It’s a win-win!

Readers, what do you think? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

To continue the Monty Python allusions, “And now for something completely different!” Judge John Hodgman has ruled on the pressing question, “Which are fancier, ducks or geese?” The whole podcast is a lot of fun, but this particular discussion begins at 28:20. Or, if you don’t have time to listen, decide for yourself:

Ducks are obviously fancier than geese, right?

For simplicity’s sake, throughout this piece I will use “college” to refer both to colleges (which enroll only undergraduates) and to universities (which include graduate programs and professional schools).

When I was an English teacher at an elite private high school, part of my job was to craft entertaining, heartfelt, and convincing letters of recommendation to help my students get into college. I spent an average of four hours on each letter and was happy to do it—I loved my students. But needless to say, kids who go to public school, and whose English teachers have hundreds of students, don’t get this kind of attention.

According to this Wikipedia page, the top 100 most selective schools have a total freshman enrollment of 200,000 and an average admit rate of 35 percent so, working backwards and taking into account that some kids get multiple offers, while others choose not to attend an elite college, we can estimate that about a half million students apply to these colleges each year. This is not a perfect estimate, but it’s probably the right order of magnitude.

I recognize that there is a lot of controversy about the SAT. While it’s beyond the scope of this post, and while I think the ACT is a better exam, the SAT does help to correct for problems of standardization across different grading systems and offsets grade inflation. Colleges could make standardized tests fairer by requiring all applicants to submit only the scores from the first time they take the test.

I have a dog in this fight, because my high school didn’t offer calculus (a school board member refused to allow it, saying that if students studied calculus, they would get “too big for their britches”). So I took pre-calc, the highest math course my high school offered. My limited high school course offerings had no bearing on my success as a college student: I tested into the top of four levels of calculus in college—the one usually only taken by a handful of math majors. I took the second-highest level (I was an English major, after all, and also a bit lazy), and got better grades than students who had had a full year of calculus in high school.

Mom, don't you know a modest proposal is supposed to be something we SHOULDN'T do?

I had a similar thought for the UC system in California. When the second-tier UCs have acceptance rates at about 20% (and the top tier less than 10%—but these are public schools, not Ivies!) there’s clearly a problem.

There are simply way more qualified kids than there are spots, so there’s a lot of pressure to take MORE AP classes, do MORE clubs, MORE volunteering, MORE sports. It’s become ridiculous, and there’s no balance for these kids.

Instead of everyone trying to get an edge and game the system (joining more clubs than the next kid; proclaiming the ethnic identity of one’s great-grandmother; etc.), California could just decide what the admissions criteria are for these rare coveted spots, and then hold a state lottery. Simple.

Benefits:

1) Kids who don’t get in would no longer feel they “failed” or should have done more to stand out.

2) If it’s not your kids’ “failure” to take the 20th AP test or join the 10th club or start a “nonprofit” that’s to blame, it becomes more obvious that a lack of space is the problem. Let’s discuss that.

3) It takes pressure off UCs to create a “diverse” class — a lottery of everyone who qualifies would tend to be diverse.

4) It takes pressure off the kids to do more than is reasonable to get into their public universities. They can have more balance in life.

It’ll never happen, for reason #2. It’s much easier for the state to blame it on the kids themselves than on a ridiculous shortage of space.