Every New Year I write about our—to me—baffling habit of making New Year’s resolutions about our health, to the exclusion of any other worthy goal. Why are we always adopting a new exercise regimen or eliminating “sinful” foods? Why not resolve instead to promote peace and harmony in our relationships, to show a bit of grace about our own and others’ flaws, to host more parties, or to seek less perfection and more joy? Accordingly, I had planned to write about this article, which claims that “people who eat broccoli at least once a week were 36 percent less likely to develop cancer than those who didn’t.” Really?! Say more! Can we simply offset the occasional beer with bites of broccoli and stop fretting about our health?1

But then I saw this image:

The horror in the 2024 picture is not the allegedly unhealthy beer the people are drinking. Far more dangerous than carbs and a bit of alcohol is the isolation, the disquieting hush, the hunched shoulders, and the grim expressions. Readers, now is the time to stand athwart our slide into dystopia, yelling “Stop!”

The Most Human Human

Nine days before my dad died, he had an appointment at the dermatologist. We walked into a deserted office and were greeted by a fake lady on an iPad:

After a few minutes, the AI receptionist called Dad’s name, and my parents went to the examining room. They were met with another iPad showing an AI nurse, which asked Dad how he was doing. “Well, not so great, actually,” Dad replied. “Terrific!” said the AI nurse.

In 2011, the journalist Brian Christian served as a control in a Turing-test competition between AI chatbots. Volunteers sat at computer terminals and chatted with someone (or something) on the other end. They didn’t know whether they were chatting with a bot or with a human being like Christian. The volunteers rated their chat partners on how human they seemed, and Christian was named “the most human human,” which became the title of his excellent book about the experience.

More than a dozen years later, Dad’s encounter with that AI nurse demonstrates the simple truth that bots are no substitute for connections between people. What better resolution for the new year than to strive to be “the most human humans” with one another?

See One, Do One, Teach One

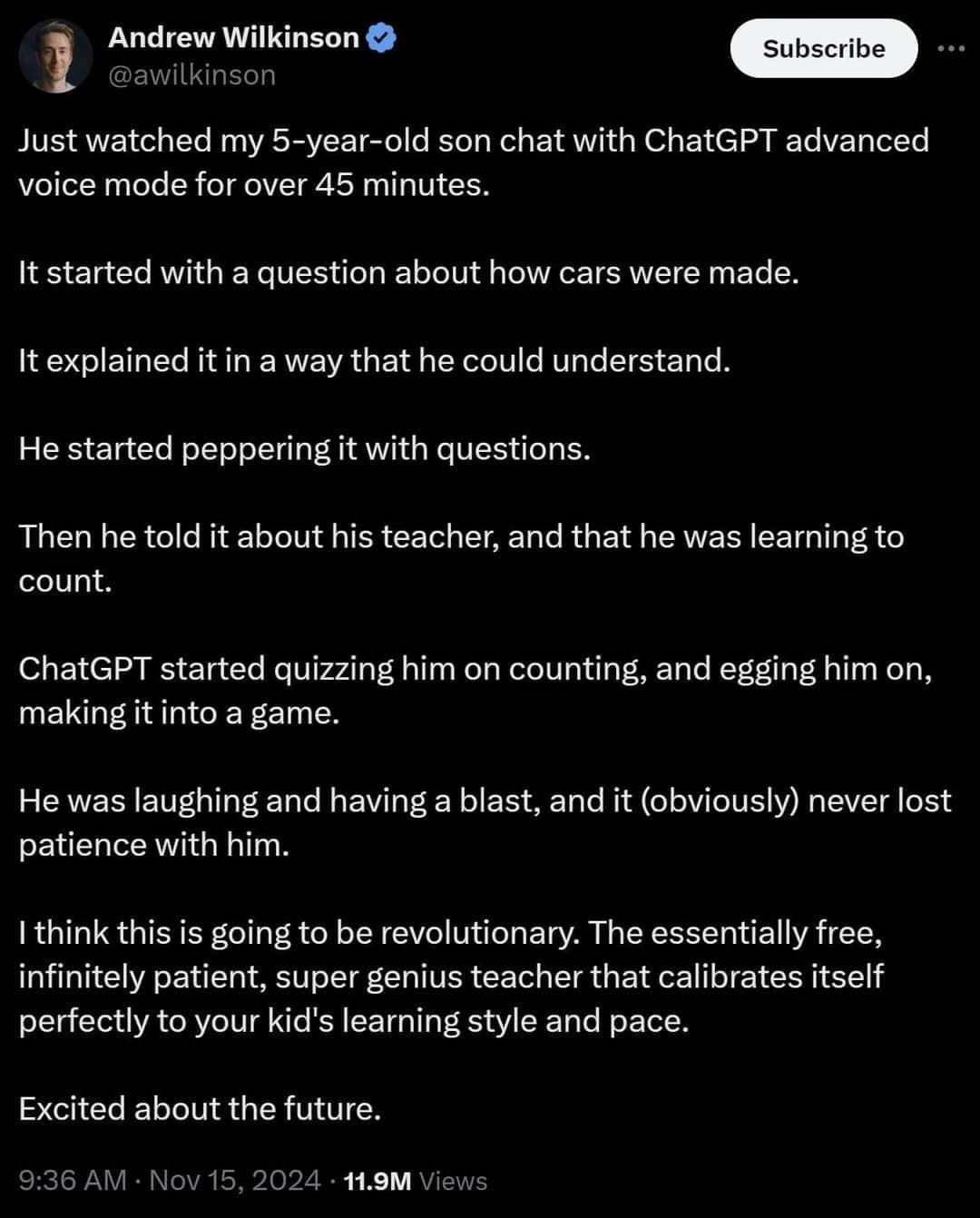

Tech bros are quite excited about AI in education and have founded companies with names ranging from the fanciful (MagicSchool) to the anodyne (SchoolAI) with the aim of replacing human teachers with chatbots. A venture capitalist rhapsodizes about the potential of AI in education:

This sounds innocuous enough, until we think back to our favorite childhood memories—of, say, building forts, playing house, hurling snowballs, chanting jump-rope rhymes, dressing up the dog, fishing with Grandpa—and we realize that none of these treasured moments involved staring at a screen. Which makes sense, because for all of human history children have learned by playing with other children, imitating older siblings and cousins, observing their parents as they go about their lives, and sharing their newly-acquired skills with younger kids. Why should now be any different?

Whether it’s for aspiring doctors or anyone else, the medical-school principle of “see one, do one, teach one” works because most of us are active learners: We need to practice inserting an IV—or that Beethoven sonata, our backhand, the Fair Isle technique, the Hamlet soliloquy. We need to test out scientific hypotheses and work through mathematical proofs. We need to bounce our ideas off our friends to see if they make sense. We need to make our own mistakes, try again, fail again, and fail better. Our schools would make a poor bargain, should they choose to feed kids facts from a bot at the cost of more enjoyable and effective interactions with teachers and friends.

Even the “infinitely patient” aspect of AI is not the boon it is purported to be. True, all children crave knowledge; when our son was little, he would have been enthralled by an AI tutor too. He used to ask me questions at an average rate of one hundred per hour (this is not an exaggeration; I counted them once), and I did my best, but eventually I would hit the wall. Which is a good thing: It is important for kids to learn that it is possible to try people’s patience! A bot will never say, “Honey, that’s enough for now. I need to drink my coffee. Go see if Frankie wants to play in the sandbox.” As anyone who has spent time with children knows, they are better off outside with friends getting their hands (literally) dirty than inside with an infinitely patient AI—or with their comparatively impatient mom.

Through a Glass, Darkly

For an ominous glimpse into the wasteland of disconnection our tech overlords have in store for us, consider the commercial, below, for the Apple Vision Pro. The worst moment comes at the two-minute mark: Two little girls are laughing as they blow bubbles, and their dad stands off to the side, face entirely concealed by the device, recording his daughters as they play. The ad boasts that the goggles let us “Relive a memory as if you are right back in the exact moment.”

Or we could just be in the moment, blowing bubbles with our daughters, and then later we could relive the memory in our very own brains. We could strive to be like a man who has learned

to see the great, eternal, and infinite in everything, and therefore . . . threw away the telescope through which he had till now gazed over men’s heads, and gladly regarded the ever-changing, eternally great, unfathomable and infinite life around him. And the closer he looked the more tranquil and happy he became.

The good news is that we are indeed “throwing away the telescope” and rejecting these barriers to authentic experiences with our fellow human beings. Google Glass was an abject failure; Meta’s VR division has lost the company billions; and, as this article in Forbes puts it, “Apple’s Vision Pro Is Amazing But Nobody Wants One.” How could it be that these outstanding products, designed by tech geniuses, are so unappealing to us normies?2 To paraphrase the wisdom of 1 Corinthians 13:12, we are coming to understand that it’s time to stop seeing one another through a glass, darkly, and to return to seeing one another face to face.

Paperclip Maximizers or Plagiarism?

“Paperclip maximizer” is shorthand for the Silicon Valley fear that AI could become sentient and, simply by following its programming, obliterate all human life. This apocalyptic scenario reminds me of South Park’s Underpants Gnomes:

The AI-doomers are missing one heck of a phase two. Before AIs can attain God-like intelligence with which to destroy the world, oughtn’t they be able to at least answer a simple question without hallucinating?

As I’ve been arguing here, the danger of AI is not that it will lead to a sci-fi catastrophe. The danger is all too quotidian. It’s the elimination of jobs that offer a comfortable middle-class life. It’s the temptation to isolate ourselves and to become addicted to an artificial online world. It’s the substitution of accumulated facts for the wisdom of experience. It’s the loss of the opportunity to challenge ourselves intellectually and to express ourselves through our own creations. As a former English teacher, I feel that loss keenly.

English classes are not just about reading and writing but about developing critical thinking skills. AI tools, such as chatbots or writing assistants, can provide quick answers or even generate essays, but they bypass the cognitive processes students need to engage with. Writing an essay or analyzing a text involves organizing thoughts, making connections, and crafting arguments, all of which are essential skills. Relying on AI for these tasks can stunt intellectual development, as students may stop engaging in deep thinking and problem-solving.

I get that it’s unjust to lay all the blame for plagiarism on AI. After all, I have written about plagiarism before, citing examples from the early 1990s, long before Chat GPT was a gleam in Sam Altman’s eye.

Yes, students are using chatbots to do their work for them, and this is pretty depressing. But the real threat of AI, VR, and the online world is not that we will plagiarize it, but rather that it will plagiarize us. Already AI is hoovering up our words and works and outputting hollow, soulless copies of our unique human creations for our ease and diversion. But we can just say no to this dystopia. We “most human humans” can refuse to allow machines to think for us, invade our relationships and creative pursuits, and take over the most meaningful, beautiful, and joyous ways to be human.

And now I have a Turing test for you! There is one paragraph in this essay that I didn’t write; I asked Chat GPT to write it for me. Can you find it? The answer is in this footnote.3

How about you, readers? What will you and your families do to live in the real world and away from bots and screens this year? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

There has been something of a backlash to the poem below, by Joseph Fasano; people find the teacher to be “too judgmental.” To which I reply, “It’s part of his job to be judgmental! Sometimes students ought to be judged!” Harumph. I think the poem is lovely. See if you agree:

For a Student Who Used AI to Write a Paper

Now I let it fall back

in the grasses.

I hear you. I know

this life is hard now.

I know your days are precious

on this earth.

But what are you trying

to be free of?

The living? The miraculous

task of it?

Love is for the ones who love the work.

I am being facetious. In my opinion, a lot of health advice in the mainstream media wildly exaggerates the risks of “bad” foods and the benefits of “good” foods to get clicks.

A clue can be found in this hilarious essay by Alex Dobrenko: “i refuse to talk to you w those stupid ass ski goggles on your face.”

It’s the block quotation about the man who has learned “to see the great, eternal, and infinite in everything. . . .”

Kidding! That quotation is from Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace, trans. Aylmer and Louise Maude, revised by Amy Mandelker (Oxford, 2010).

The Chat GPT passage is the penultimate paragraph in the Paperclip Maximizer section, beginning “English classes are not just about reading and writing. . . .”

While I am well aware that I am vastly inferior to Tolstoy, I hope that my writing is sufficiently quirky and diverting—and the AI writing sufficiently bland and generic—that it was easy for readers to identify the AI paragraph.

For another Turing test, check out this article in the New York Times, in which the novelist Curtis Sittenfeld and Chat GPT each write the opening to a novel. I predict that you will have no trouble telling which is which.

"now is the time to stand athwart our slide into dystopia, yelling “Stop!" Who would have guessed that the reality of modern life has so mugged our belovedly progressive Mari that she has adopted the stance of 1955 William F Buckley. Turn, turn, turn indeed. Welcome to my world of old curmudgeons who remember a better time . . . and long for it again.

I find myself of mixed opinions about that poem. On one hand, yes, you do want people to show up. On the other hand, all having to write essays in school did was give me a HATRED of writing and a STEMlord's conviction that English is for pretentious wankers. I would have happily told AI "give me 500 words on Biblical symbolism in Hugo" and gotten some sleep, probably gotten out ahead.

I'm right in the target demographics for early AI adopters, yet I feel myself hesitant. On one hand, I'm a hikkikomori with few friends (and none IRL), and as far as I can tell, most of the interactions people have with each other are fake, anyway. Yeah, LLMs are the definition of "confidently wrong," but people are full of shit too. Yeah, you'll never make a genuine connection with a machine...wait, I've never made a genuine connection with a human being. The only reason I'm not climbing down that rabbit hole is because there isn't a single client I'd trust to remain open source, transparent, and NOT for profit.