This is the first of four posts on how we can make family life happier and more appealing for everyone. I believe that Gen-X parenting is not only easier for parents but also better for kids. A win-win! Look for the following posts in the next few weeks:

Sometimes You Just Have to Be Thirsty

I am torn about “fertility crisis” discourse. On the one hand, some natalists give off disquieting eugenics vibes, and many pro-fertility types evince a desire to put us women in our place—which is apparently the home and nowhere else.1 I believe that how people choose to live their lives is no one else’s business, and that childfree people have as good reasons for their choices as we parents have for ours.

On the other hand, the number of births per woman worldwide has dropped to an all-time low and is now below replacement (2.1 children per woman) in nearly every developed country. The current fertility rate in the US is 1.6. This is, if not a full-blown crisis, at least concerning, because we need young people to participate in the economy and to care for elders. If we stop having kids, the system collapses. But also, never mind these practical concerns. We need children because children are lovely! They’re imaginative, funny, and full of energy and wonder. They teach us to slow down and appreciate the world and one another. They give us hugs—and also hope for the future.

What the Weird Trick Is Not

Across the political spectrum, no one has found the perfect plan for persuading young people to start families. Prominent conservatives like J. D. Vance seem to believe that scolding and shaming childless people will do the trick—when in fact most people respond to ridicule by digging in their heels and giving as good as they get.

Right-wing organizations like the Heritage Foundation advocate for draconian methods—for example ending no-fault divorce, restricting access to contraception, and discouraging higher education for women—to push Americans to have more children. But the architects of Project 2025 haven’t turned The Handmaid’s Tale into a documentary (or they haven’t yet, she said darkly). A centrist approach, practiced in many countries, is to pay families cash bonuses for each child. We received an annual tax rebate from the Swiss government when our daughter was in high school, for example. These payments are a welcome help for families, but they don’t raise the fertility rate.

Policies supported by the left—such as universal healthcare, paid family leave, affordable childcare, free or cheap higher education, and a reasonable work-life balance—are crucial for families’ health and happiness, but the evidence shows they don’t increase fertility either. Even those countries with robust support for families have fertility rates well below replacement. A social safety net is necessary for encouraging young people to have kids, but it’s apparently not sufficient. What to do?

Men Don’t Make Passes at Girls Who Wear Glasses

Before we get to the weird trick, let’s take a brief detour to talk about eyeglasses. We’re all familiar with those scenes where the bookish Plain Jane takes off her glasses and suddenly becomes hot.

What about those of us who don’t turn into bombshells when we take off our glasses? What about our needs, hmmm? Anyway, as a bookish Plain Jane myself, I drew the obvious conclusion from these scenes that glasses would make me undesirable and were thus best avoided. And for medical reasons (“tight lids”), I couldn’t wear contacts. So I squinted at the blackboard2 and blundered around in a blur. When I was twenty, I finally got glasses, and my world changed. Suddenly buildings had sharp edges and trees had leaves and branches! My professors had wrinkles! I could recognize my friends by their faces, and not just by their voices and gaits! There was so much beauty in the world that I had been missing!

I actually have a point here. Before I got my glasses, I only knew about the bad bits—the expense, the hassle, the unattractiveness. I couldn’t even glimpse (literally) the delights that awaited me once I could see.

Similarly, if we don’t have personal experience with little kids, it’s much easier to focus on the negatives. Our culture is all too ready to tell us that having children is difficult—that pregnancy and childbirth are hard on our figures; that we must give up our youthful, devil-may-care spontaneity; that we will lose sleep off and on for the rest of our lives; that we will stop being the main character in our own story. And all of this is true. In addition, people who don’t have children in their lives might only notice kids when they’re careening around fancy restaurants, crying on planes, or tantruming in grocery stores.

It is good that we no longer pretend that family life is all sunshine and rainbows. But I think we have overcorrected and now only talk about the tough parts, which obscures the beauty that children bring to our lives. To continue the glasses metaphor, we need to give young people a new lens through which to see family life clearly, with its challenges, yes, but also with its deep meaning and joy.

The Weird Trick Is Babysitting

Gen Alphas, Zoomers, and younger Millennials are the first people in history who have not had any responsibility for, or even much contact with, little children. Most of our current young people have grown up with few (or no) siblings or cousins; very few of them have played freely in large, mixed-age groups of neighborhood kids; and almost none of them have been babysitters. The consequence is that it is rare for young adults to have had positive experiences of playing with and supervising young kids.

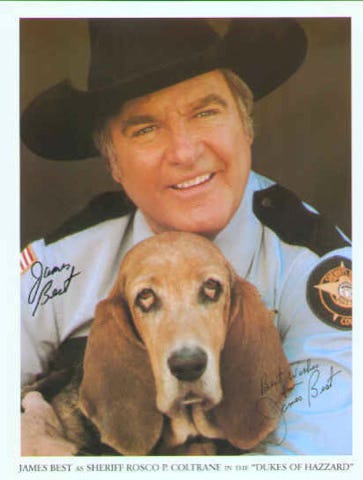

When I was a middle-schooler in the late seventies, it was normal for girls (and some guys) to babysit. I babysat kids ranging from babies to ten-year-olds beginning when I was twelve and continuing through high school. A very tall family hired me because I am tall3 and could be a positive role model for their daughter, Kelly. We played “model”: Kelly would pose and strut, her little brother was the photographer, and I was the hairstylist. Another family used to hire me to take their kids biking in a nearby nature reserve, where we once spotted a magnificent buck. I learned that belting out pop songs is a great way to transfix a wriggly baby so he doesn’t squirm off the changing table. My charges and I played games, raced around the park, read books, made art, told stories, baked cookies, ate treats, snuggled at bedtime, and, if the kids were especially good, watched The Dukes of Hazzard.

Babysitting taught me that it is tremendous fun, and richly rewarding, to hang out with children. It’s one reason I wanted kids of my own.

Blame Harvard

If babysitting is so great, why don’t more teenagers babysit these days? One reason is competition for college admissions. Teenagers are responding to incentives when they choose not to babysit. When our kids were little in the early oughts, date nights were impossible because all the high schoolers—and probably also the middle schoolers and maybe even the elementary schoolers—were too busy building their resumés to have time for something as unimpressive to college admissions officers as babysitting. Parents nowadays often resort to electronic babysitters—iPads and iPhones—because if any babysitters are to be found they cost an arm and a leg.4 I don’t blame parents, who are making the best of a bad situation. I blame Harvard, and other elite colleges, for incentivizing a meritocratic rat race, instead of authentic connections between people.

Action Plan

What can we do? We can implement this one weird trick in our own lives. Why not get together with a group of friends or relatives, including kids of all ages? We can let the older kids take charge of the younger ones while we enjoy adult beverages and conversation. I promise the big kids will be eager to babysit, because we will pay them. (We don’t work for free; why should teens?) Confiscate the phones, turn the kids loose, and let the wild rumpus start. We can also talk with other parents in our neighborhoods about the importance of babysitting. If our kids are in middle or high school, we can encourage them to babysit, and if they’re little, we can stop worrying and learn to love the teenage babysitter.

But what about the (perhaps apocryphal) college admissions officers who would reject applicants because they spent their spare time babysitting, and who only care about Wunderkinder with stellar resumés filled with lead roles, athletic achievements, and expensive service junkets to developing countries? Well, those admissions officers can take a long walk off a short pier. We older and wiser folks know that babysitting is the most valuable extracurricular activity of all, because there is no more important work than caring for one another.

How about you, readers? Did you do any babysitting as a kid? What are your favorite memories? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

As promised in my previous post, below is the most romantic scene in film history, from How to Marry a Millionaire. David Wayne tells Marilyn Monroe that even without her glasses she is “quite a strudel,” but that her she looks even better in her glasses, because they give her face “a certain mystery . . . and a certain kind of distinction.” Swoon!

Fertility-crisis discourse is currently right-coded, but it shouldn’t be. For a glimpse of how bleak a childless world would be—and an argument that conservative family policies and extreme meritocracy lower the fertility rate because they make childrearing so difficult—I highly recommend Gideon Lewis-Kraus’s article about the situation in Korea, “The End of Children,” in this week’s New Yorker.

Except in math, where my friend Eric helped me out. His glasses were broken, so he would pop out one lens and hand it to me, and I would hold it in front of my face and peer at the board through it. For some reason I thought this was more appealing than just wearing glasses.

My height is also the reason I was hired by a very short family to babysit their son. They lived in a Victorian house with high ceilings, and they couldn’t reach the top shelves in their kitchen, even with a stepladder. So every time I came over, there would be items on the counter for me to put back on the shelves as well as a list of items for me to retrieve.

I am reliably informed by a friend of our son’s that the going rate for a babysitter in DC is $40 per hour.

This is a fascinating one. Speaking as a childless woman, never married, who is 39.5 (and yes, as a childless woman in my late thirties, I'm very aware of the .5, and I tend to view life in 9-month increments), I find that most articles about the fertility crisis miss the basic problem. It's not that we don't want children or aren't used to them (I babysat other people's children, which I hated, but I loved spending time with my half-siblings who were born when I was in high school - from them, I learned about the joy of watching a child's personality develop and helping them discover their sense of humor and understanding of the world). It's also not that we, highly intelligent adults, can't handle delaying gratification or putting off our own pleasure (like many of my female friends, I spent 6 years getting a PhD, then many years underpaid in academia - much less joy and reward than a child, and a similar effect on one's social life).

Almost all of my female friends and many female cousins my age, all of whom are very smart and well educated, have wanted children at some point. (The one exception is a wonderful, loving, nurturing friend whose mother is clinically psychotic.) Among those women, the ones who found stable partnerships in their 20s or 30s and have not had fertility problems have all had children - the majority of them two, three, or four children - even the women who are family breadwinners in low-paying jobs.

Among my friends, those of us who haven't had children haven't had them either because of infertility problems (one friend went through menopause at 32, while trying to persuade her male partner to have a baby; now she sees him on dating apps, seeking women to have children with) or, as in my case, because we have not found partners with whom to have them. I have been trying from the age of 25, quite energetically and despite endless disappointment, to find a loving relationship - with a partner of either sex - in which to have a child. It hasn't happened. I've had the option with a few boyfriends, but they were relationships that were clearly not going to last, and as the child of a baby boomer marriage that ended painfully when I was 5, I have always felt that I would never, ever put a child through a parental divorce.

So the real question, for most childless women I know and have met, is whether to give up on finding a partner and try alone. The cost-benefit calculation here is agonizing. There's the option of egg freezing (which is notoriously ineffective) or embryo freezing (which works better but forecloses the possibility that a future male partner could be the biological father). The narrative is usually one of freedom and choice, but a close female friend of mine who is a doctor decided against egg harvesting because of the associated cancer risk. My aunt died of ovarian cancer, and this is not a risk I feel comfortable taking.

One close American friend's sister recently had a baby on her own at 41. She's an executive at a major international firm, lives in Europe (hence maternity leave and benefits), makes a vast amount of money, continues to travel constantly for pleasure with the baby, can afford any help she needs, and had embryo freezing and all other fertility treatment paid for by her employers. Another close British female friend recently had a baby on her own at nearly 41, after five years of trying - miscarriage in a failing relationship that she only kept going in order to become pregnant, followed by many solo IVF rounds. She spent GBP 40,000 on her baby, on an academic salary. She has retired parents with whom she is close; they all sold their houses and moved to a larger one in the country where they now live together so her parents can help with child care. She was able to arrange 2 years of leave from her academic job (in exchange for a lot of admin work before the birth, and including maternity and research leave) and will be able to work 2 days a week in person when she goes back.

I'm very happy for both these solo mothers - but how many women have these options? Further, these are both women for whom having a child has always been more important than finding a relationship with a partner. I've always wanted a loving adult relationship as much as, or more than, I want a child, and choosing to have a child on my own feels like limiting the possibility of finding such a relationship.

These are the considerations that educated adult women, in my experience, actually have to deal with. Babysitting, unfortunately, is not going to help.

I grew up in the 70’s and regularly babysat for local parents, the benefits were great…unlimited snacks and after the kids went to bed I could listen to their LP’s, a much better selection than my parents had! I recall one dad would pick me up in his Porsche! Later when I had my own kids I belonged to a group of moms (and dads) who babysat for each other for credit hours! No money exchanged hands and it was rare you couldn’t find someone who could help. Now I hope to be able to help out with future grandchildren, all being well! Just one thing, pertaining to your group get togethers. When my kids were about 14 months old they still hadn’t started walking, we went to a large group camp and the preteens loved taking my twins by the hand and walking all over the campsite with them (we loved it too as we could do our own thing with our friends). By the end of the week they were walking all on their own! Everyone benefited!