Grudges

And What to Do about Them

A couple of weeks ago I wrote about forgiving Mel Gibson and made the case that we are usually better off if we are able to forgive people who have injured us. However, I don’t want to mislead readers into thinking I am some saintly person, because I can definitely hold a grudge. To wit, the following story:

One year when I was in college, I lived in a large apartment with roommates, whom I’ll call Amy, Belinda, and Diana. While Diana remains one of my best friends to this day, trouble with Belinda reared its head early on, when she sprang two stray cats on us (one was feral and mean; the other was admittedly cute) and then decamped for long weekends to visit her boyfriend in another state, leaving us to handle the litter box (which she left in the kitchen—yes, yuck). Worse, Amy and Belinda let their friend Claude, a stranger to me and Diana, move in without asking us first. (Claude turned out to be a mensch, though; see below.) But the final straw happened that spring, when Amy and Belinda

Planned a party without consulting me and Diana;

Made it clear that we weren’t invited (we had to vacate the apartment and sleep at Diana’s parents’ house);

Advertised the party, including our address, in the social calendar of the student newspaper, which is why hundreds of people (not an exaggeration) came to the party;

Mentioned in the invitation that “The square roommate won’t be home, so we can have fun!” and

Left a disgusting mess—the plumbing had been overwhelmed by the hundreds of people using our toilets, and black, slimy sewage backed up into the the tub and shower and all over the bathroom floors—for Claude, Diana, and me to deal with.1

Neither Amy nor Belinda ever apologized. I rarely think about this incident, but when I do, I get angry all over again, even though this was a minor blip in a long happy life, and even though the very public blot on my escutcheon from being labeled “the square roommate” in the paper faded eventually. I held onto that grudge for quite a while!2 Yes, we should strive to forgive others, for their sakes and ours, but grudges are only human.

A Brief Defense of Grudges

Grudges are an immune response; they protect us from injury by reminding us that certain ways of treating us are unacceptable. I recommend this episode of the Judge John Hodgman podcast, “Grudge Match,” in which people share their grudges over such petty offenses as the theft of a barrette or being tricked into eating bananas. As the Judge puts it,

This is an evolutionary issue. When you touch something hot and it burns, you remember. When you chop down a tree with an ax, the ax doesn’t remember; the tree remembers. Pain sticks with us. Sticks in our craw. Maybe that’s what the craw is for.

When a person injures us and doesn’t apologize, there is a danger that we will blame ourselves or believe that we somehow deserve such treatment. I have found it helpful in these cases to—as I call it—pull an Elizabeth Bennet. Mr. Darcy insults Elizabeth at a ball (“She is tolerable, but not handsome enough to tempt me; I am in no humor at present to give consequence to young ladies who are slighted by other men”), and Elizabeth runs to her friends, who reassure her that she is the injured party, and that Mr. Darcy is not behaving like a gentleman. After Amy and Belinda mocked me in the university paper, a couple of friends called to tell me they thought that my roommates were out of line, and that my grudge was justified. Which helped! Grudges, and their endorsement by our loved ones, teach us to expect better from other people.

Forgive and Forget

That being said, we are often better off when we choose to forgive (or at least forget). As the saying goes, “We don’t forgive for them; we forgive for us,” and sometimes holding on to a grudge is costing us more than letting it go. A recent article in the New York Times offers tips to help us let go of our grudges, and, if we need an incentive, points to a study showing that forgiveness “reduce[s] symptoms of anxiety and depression.” As one of the study’s authors notes, forgiveness “free[s] the victim from the offender … and is a better alternative to rumination or suppression.”

Let me share another story, in which I was the one who was forgiven. Many years ago, I was driving through town somewhat distracted by my kids, then a toddler and a preschooler. I glided up to a stop sign, took a cursory look, and rolled into the intersection, where I hit another car, which had right-of-way. Even worse, I recognized the other driver, Carol, a worker at our local Trader Joe’s. Needless to say, Carol did not need this aggravation and expense in her life; when she got out of her car she was crying. I felt terrible, and even though we’re not supposed to admit fault after a car crash, I apologized right away. Whether it was because of my quick apology or Carol’s kind nature, she wasn’t angry with me and was more worried about my kids (who were thankfully fine) than about her car.

But another reason Carol forgave me is that I didn’t just offer empty words. I made amends. Our insurance paid for her car repairs, provided a replacement car while hers was in the shop, and reimbursed her for lost wages. (She later said to me in amazement, “You have really good insurance!”) We wound up becoming friendly, and after that, whenever I ran into her at the Trader Joe’s, we would have a nice chat, and she was always eager to hear updates on my kids. It is so obvious to me that forgiveness was the happier, healthier route for both of us. Readers, if you have the opportunity to forgive someone who has apologized and made amends, but you are still angry or are feeling reluctant, believe me, I get it—but I also hope you will think of this story, and about what a blessing forgiveness can be for both parties.

Or Never Forget

On the other hand, some offenses are so egregious, and some victimizers are so callous, remorseless, and manipulative, that the demand for forgiveness compounds the moral wrong. In these cases, a grudge protects the victim from further abuse and sends a message to the world that some crimes are intolerable and unforgivable. Take the case of Women Talking, which I discussed a couple of weeks ago. In both the real incident and its retelling in the book and movie, the men of the colony plan to force the women and girls to forgive the men who drugged and raped them. We know that the rapists are impenitent; if they felt guilty, they would have agreed to remain in jail. The other men of the colony apparently don’t take the crimes seriously either, because they drain the colony’s assets—even taking away the women’s beloved horses—to pay the bail. In this situation, the forgiveness the men are demanding would be tantamount to permission for the abuse to continue.

Similarly, Simon Wiesenthal, in his book The Sunflower, describes a situation in which forgiveness could be seen as immoral. Wiesenthal, who was enslaved in a labor camp during the Holocaust, recounts the true story of being summoned to the bedside of a dying Nazi officer. The Nazi requests that “a Jew” be brought to him to hear his confession and absolve him of the crime of murdering more than three hundred Jews, including little children, by burning them alive. As the Nazi speaks, Wiesenthal shoos a fly away from the Nazi’s face. He responds instinctively to relieve suffering, even though the sufferer is a mass murderer. And yet after the confession Wiesenthal walks out of the hospital room in silence, neither condemning nor forgiving the Nazi. Wiesenthal asks fifty-three religious leaders and philosophers what they would have done in this situation, and their responses make up the last half of the book. Most of their essays advocate for forgiveness, but I find the unequivocal response of the novelist Cynthia Ozick more appropriate: “Let him die unshriven. Let him go to hell. Sooner the fly to God than he.”

Or Forget and Understand

On the other other hand, most of us are lucky never to have suffered from such unrepentant evil. For lesser offenses, even if we don’t forgive, we can at least let go of our anger, at least most of the time. It has been decades since I indulged myself in nursing the grudge against my roommates, or indeed thought about the party at all. I only remembered it when I was casting my mind back for a good story to start off this post. In fact, I have let go of this grudge to the extent that my daughter’s middle name is Belinda’s real name.3 If we stop feeding our grievances, they wither away, and that is a good thing.

And when we forget our anger, we become open to understanding and to compassion for the struggles of other people. When I was in grad school, I had another challenging roommate, who could make life in our apartment rather unpleasant. When she thought the apartment was getting too messy, she would stomp around yelling “I sense grossness! I sense grossness!” She complained that my footsteps were “too loud” and requested that I walk on tiptoe so I wouldn’t annoy her.4 I moved into my own place shortly afterwards and didn’t give her another thought, until one day I had an epiphany: “Oh! She must be on the spectrum!” And then I wished that I had realized this earlier; were it not for my irritation at her, I would have, and maybe things between us would have been easier.

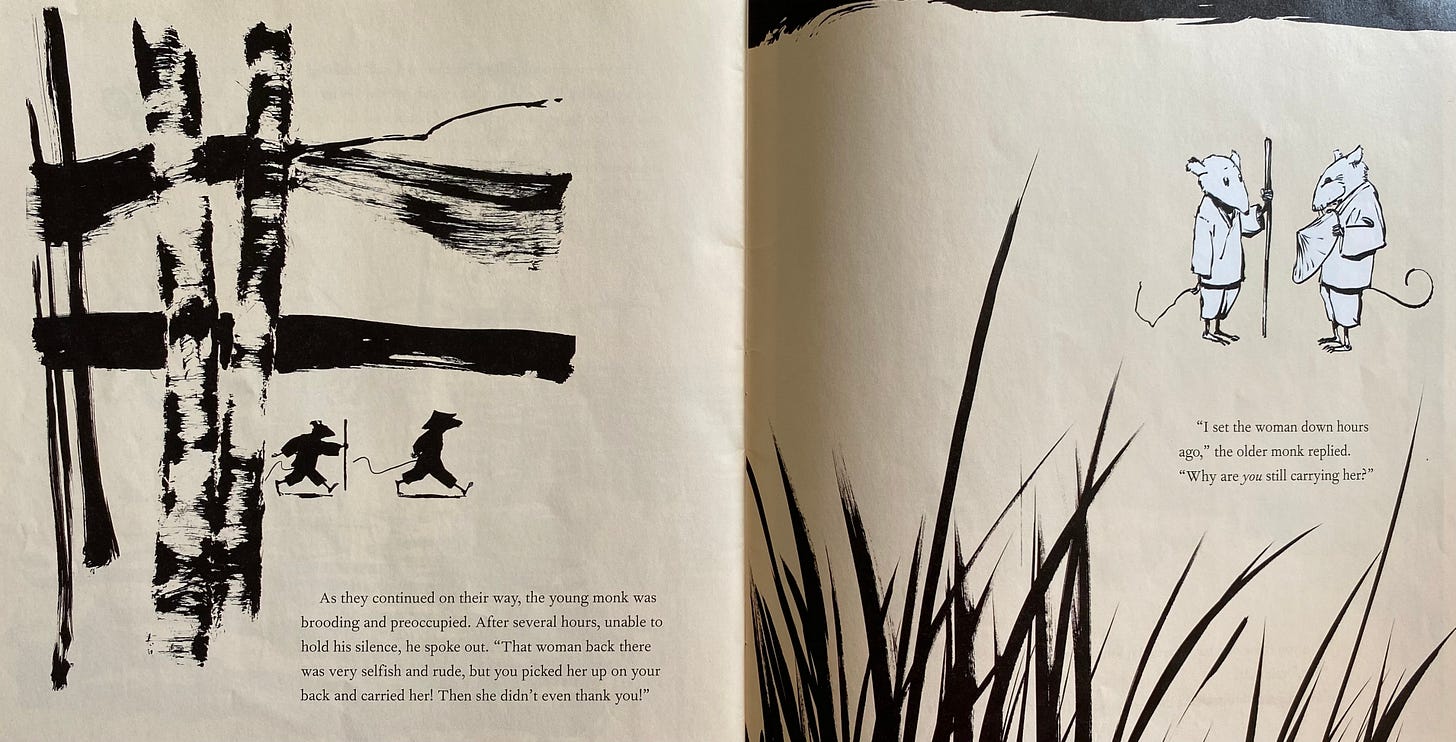

Speaking of tiptoeing, let me tiptoe briefly into the culture wars. When we hear about someone doing or saying something awful—for example Mel Gibson’s aforementioned antisemitic tirade or Amy Cooper’s calling the police on an innocent Black man—it is only natural to get angry. However, we err when we escalate that anger into calls for punishment, with no possibility for mercy or forgiveness. “Our collective intoxication with public shaming” is not good for us or our country. We don’t need to have an opinion about everything we read about; still less do we need to dragoon every incident into one side or other of the culture wars. Instead of ratcheting up outrage at malefactors and demanding they be cast into utter darkness, what if we tried empathy? It is a sad truth that afflictions such as mental illness, stress, poverty, addiction (Gibson), or PTSD (Amy Cooper, who had been sexually assaulted) can cause people to behave badly. When this happens and the person apologizes, why not choose forgiveness? Or, put another way, and to paraphrase the Buddhist story about the two monks and the old woman, Christian Cooper set Amy Cooper down ages ago. Why are we still carrying her?

Beef Is an Allegory for America

I’ve been watching5 the Netflix black comedy Beef, a powerful allegory for the divisions in our country. Our inability to extend understanding and forgiveness to people on the other side of conflicts can lead to disaster. As readers likely know, the show dramatizes the escalating consequences of a road rage incident between Danny, a working-class striver, and Amy, who, while rich and privileged, is unhappily supporting her deadbeat cheater of a husband and his querulous mother. Both Amy and Danny are under terrible economic and family stress, and both are by nature grudge-holders, and so neither can let the incident go, and a cycle of revenge and counter-revenge ensues. At any stage, had one character (or both) let go of the grudge, they could have become friends like Carol and I did, or at least avoided needless suffering.

The irony is that Amy and Danny have a lot in common and could have been allies against their true oppressors (a self-satisfied and exploitive billionaire in Amy’s case and a sociopathic cousin in Danny’s). In the second episode, Danny drops by Amy’s house and, thinking the road-rager was her husband, bonds with her over the stress of being an overachieving child of immigrants. Later in the show, as the two characters are having a parley, another driver honks at them, and they both turn on the other driver and, in unison, unleash a hilarious torrent of abuse at him. These two scenes point to another possible ending for their conflict, had they only been able to look past their differences to see all that unites them, and then to extend a bit of understanding to each other.

We Americans have the opportunity to choose this happy ending for ourselves, if we approach political conflicts with a bit of understanding and grace—and a bit less readiness to hold a grudge. As Benjamin Franklin said, “We must, indeed, all hang together, or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately.”

So what do we do about our grudges? As you may have noticed, this essay has vacillated between advocating for forgiveness and defending grudges. Forgiveness can be a wonderful thing, but it is rarely as simple or attainable as spiritual leaders and psychologists make it out to be. Sometimes we feel lightness and relief when we are able to forgive—but sometimes we need to revel in the righteous indignation of a grudge.

How about you, readers? Do you have any grudges? If you share them in the comments, I promise that we will all say, “Oh, that is AWFUL! No wonder you’re mad!” Alternately, have you ever forgiven someone—or been forgiven? How did it feel? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Judge John Hodgman is undoubtedly correct that grudges are an evolutionary issue, because animals hold grudges too, as anyone who has ever bathed a dog knows.

The most famous grudge-holders in the animal kingdom are crows. Crows are such grudge-holders that they teach the grudge to other members of their group and even to subsequent generations. This entertaining article tells of a disabled woman who was avenged by a murder of crows. Her neighbors started a feud with her because she parked in the handicapped spot, which they had been (illegally) using to store their trucks. The woman befriended some crows and fed them vegetable scraps. So the crows took revenge for her: They picked up rocks, flew high above the neighbors’ trucks, and dropped the rocks on the trucks, denting them and cracking the windshields. You go, crows!

While Diana and I mopped and scrubbed, Claude handled the siphoning and plunging. He even sucked on the hose to get the siphon to the backyard started. (Claude is a pseudonym, by the way. I would love to give my former roommate credit for his plumbing prowess and intestinal fortitude, but we fell out of touch, and I didn’t want to use his name without permission.)

Wouldn’t you?

Allow me to recommend the approach to conflict resolution my husband used in this situation. He has always loved Belinda’s real name, but when he suggested it for our daughter’s middle name, I balked because of bad associations with my former roommate. My husband noted, quite reasonably, that my daughter would rapidly eclipse the roommate in my thoughts and feelings, but we remained at an impasse until it was time to leave the hospital. Before we could go, I had to give the nurse a middle name for the birth certificate. Instead of arguing, my husband said, “I’ll go get the car. You do what you think is best.” Total ninja move, right? It worked!

Readers may sense a theme here. Yes, I have had some dubious roommates (and I concede that I may myself have been a dubious roommate on occasion, what with all that objectionable walking and whatnot)—which is why I quit living with roommates. I’m all for learning to get along with others, but some people can be a bit too challenging, and some quarters can be a bit too close.

I should mention that I have seen the first seven episodes but am not sure I will continue. The series is excellent—brilliantly written, powerfully acted, and bitingly funny—but it gets dark, and so while I do highly recommend it, readers who prefer lighter fare may want to give it a miss.

If I remember right the Christian Cooper situation was much more complicated than originally reported (surprise!). He’d made threatening comments to several other women in the park before and his actions towards Amy were more ominous than first described.

Belinda sounds horrible. I would have moved out right then (though easier said than done)! And the sewage! Actual sewage is where I draw the line. Malign me in the school paper but I can’t handle sewage.

I wonder if it’s easier for people to cultivate forgiveness as a trait if they have experienced something truly unforgivable. Every other “garden-variety horrible thing” seems not so bad in comparison. Maybe?

It’s a bit like pain. If you’ve experienced the pain of childbirth, nothing other than that can be really said to “hurt” -- not seriously.