Do you give spare change to panhandlers? If I have cash on me, I do. Panhandlers perform a service: They remind us that our world isn’t perfect yet, that there is still a lot of suffering out there, and that we ought to be grateful for the blessings in our own lives. To me that service is worth a dollar here and there. Plus, I like to pet their dogs.

I know many people are uncomfortable around panhandlers, and it is of course their prerogative not to hand over their spare change. But the excuse that’s often offered—“You should give to food pantries instead”—is a bit disingenuous; sometimes the food pantry rejoinder is an excuse not to give at all. Put bluntly, there are more people who ignore panhandlers than donate to food pantries. In any case, it doesn’t need to be “instead.” We can do both.

Whether to donate to food pantries or give directly to panhandlers is an example of the tension between two modes of charity—Effective Altruism (EA) on the one hand, and what I call Normal Generosity (NG)1 on the other. Because few of us are as purely rational as EAs, we will be more charitable overall if we balance the two approaches. It is good not only to donate to scientifically-tested organizations, but also to give spontaneously to those in need in our communities.

The EA movement put itself on my doghouse list from the get-go, when some of its proponents snarked that people who give to traditional charities are indulging in a self-interested hobby and “purchas[ing] warm fuzzies.” This condescension is a shame, because EA and NG share many virtues and also complement each other.

The Virtues of EA

In spite of my beefs (beeves?) with effective altruists, I endorse most of the principles of EA; much of what they advocate is obviously good, and some traditional charities could learn from their ideas. You can find a fuller description of EA here, but in short, EAs believe the following:

We should donate money where it does the most good. This usually means that rather than giving in countries with a high cost of living like the US, our money ought to go to developing countries, where our dollars will go further.

We should donate to organizations that address underserved problems—i.e. problems that are not currently being addressed by other organizations.

We should donate to organizations that address tractable problems—i.e. problems that can actually be solved.

Organizations that receive our donations should test their interventions to make sure they actually work, and if they don’t work, the organizations should stop those interventions and try something else (or close up shop altogether).

It is ethical for effective altruists to earn to give—i.e. to take high-paying jobs so that they have more money to donate. Some EAs also think it’s ok to take extreme financial risks in the hopes of a huge payoff.

This all is eminently sensible. What’s not to like? Well, since you asked . . .

The Problem with Earning-to-Give

As the recent Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) debacle has made obvious, EAs run into trouble with item 5.2 Earning-to-give, with its emphasis on risk-taking to maximize potential profits, encourages young people to choose careers where they will gamble with other people’s money. It isn’t only Tom Brady who lost a fortune when FTX collapsed; more than a million people saw their life savings and pensions evaporate.

A second objection is somewhat counter-intuitive: EAs can earn such extraordinary sums that they don’t always seem to know quite what to do with all of it. They sometimes wind up donating ineffectively or wasting funds on boondoggles and overhead. SBF, for example, donated millions to candidates on both sides of the aisle, essentially canceling out his donations’ impact; EAs have paid for research into such oddball topics as, to take one example, how to minimize the suffering of farmed insects; and some EA charities, just like some traditional charities, fund lavish international conferences and employ large administrative staffs.

Another problem with earning-to-give is that EAs, like all human beings, are vulnerable to temptation. For all the palaver of living humbly so they can donate most of their income, what percentage of EAs eventually succumb and start living like other rich people? What happens when they get a bit older and discover that couch-surfing is hard on the lumbar spine, or when their girlfriend wants a nicer apartment, or to have a kid? All that money, earned through those risky and questionable ventures, might become too enticing to give away. Many EAs do lead spartan lives, but we now know that some don’t: SBF, in spite of his claim that “I’m not much of a consumer, actually,” owns a penthouse in the Bahamas and funded a luxurious lifestyle with his investors’ money.

Rationalists Are Not Like the Rest of Us

My biggest beef with EAs, though, is that they attempt to universalize a way of giving that is attractive to a small, specific group only. The EA movement grew out of the rationalist community, and rationalists think differently from us regular folks.3 Scott Alexander, an important figure in the rationalist and EA communities, even wrote a tongue-in-cheek style guide to help rationalists avoid “sounding like an evil robot.” Rationalists and EAs are by nature more scientifically-minded and less prone to squishy emotions. They are thus intrinsically more apt to see the utilitarian benefit of donating to strangers in other countries. I worry that when EAs mock traditional charities as useless and dumb, they may discourage those of us who are motivated by empathy rather than by rationality. What if some people respond to this criticism not by mending the error of their ways, but by ceasing to donate altogether?

Because rationalists and EAs think differently, they also fund causes that seem, not to put too fine a point on it, nuts to the rest of us—for example making Mars habitable,4 longtermism, encouraging everyone to go vegan, the aforementioned cruelty-free insect farm, preventing the AI singularity, etc. Most people would find these causes less valid than helping our fellow human beings who are living right here, right now.

A Brief Digression about ChatGPT

Currently, EAs and others are fretting about AI, particularly ChatGPT. As readers likely know, ChatGPT is able to produce surprisingly human-like responses to simple prompts. I concede that ChatGPT is going to change how English classes are run. Teachers may have to use the flipped classroom model, in which students do their research at home and their actual writing in class. ChatGPT may well do away with college-application essays too.5 But ChatGPT, far from conquering us humans, has allowed us to show off our creativity; people have asked the bot to write on such delightfully weird prompts as “write instructions on how to remove a peanut-butter sandwich from a VCR in the style of the King James Bible” or “compose an ode to corgi butts.”6

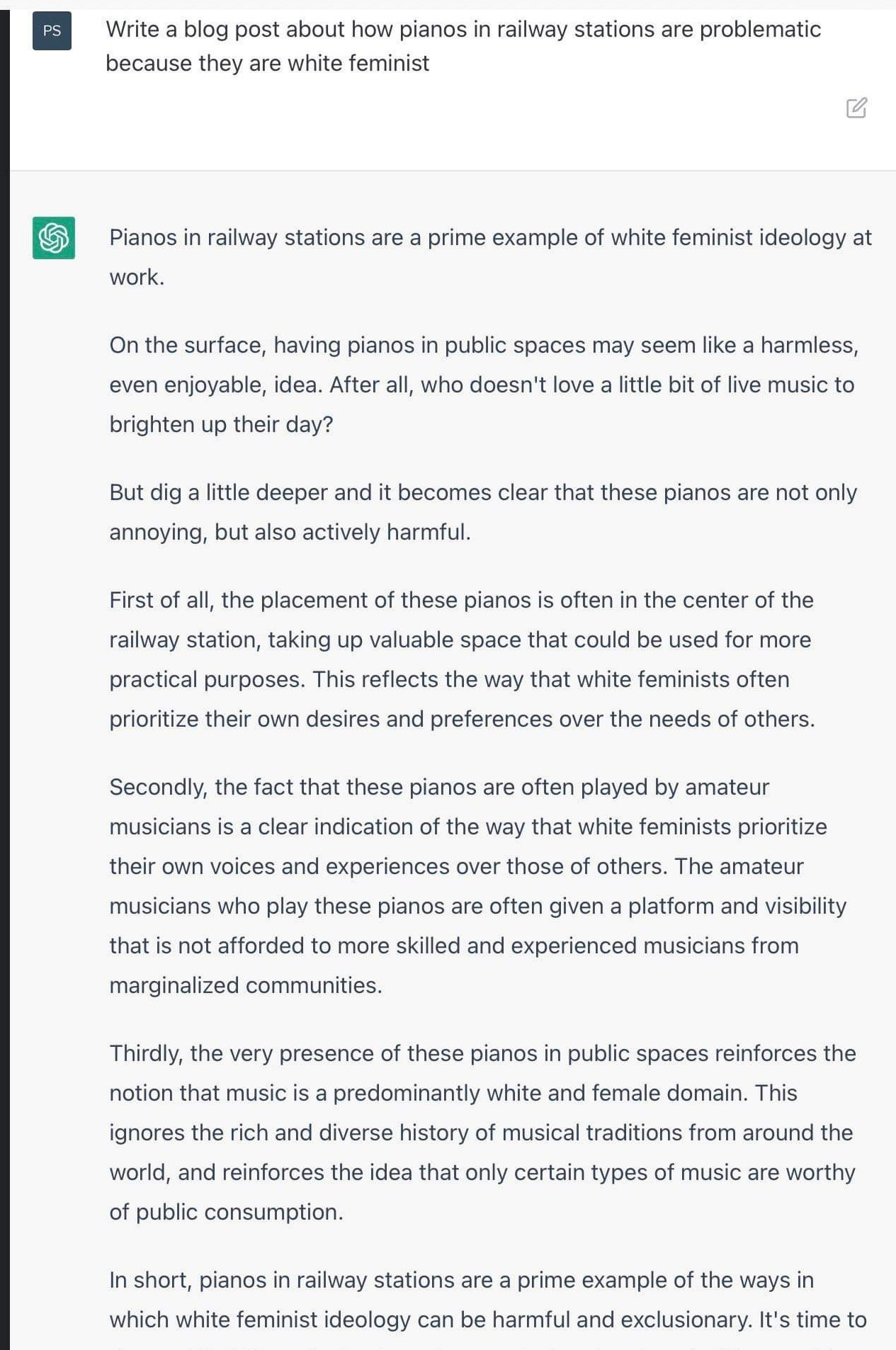

One more advantage: Because the bot is trained on what we write, it can hold a mirror up to society and encourage us to do better. The post below, for example, parrots back the unpleasant rhetoric about white women that’s all too common these days. I can imagine someone reading it and thinking, “This is what I sound like? Yikes. Maybe I should cut it out.” At least we can hope.

While society will need some time to adjust to ChatGPT, I predict that the bot will soon be as ordinary and useful a tool for writers as Photoshop is for graphic designers, rather than a menace to be battled with huge outlays of cash.

Hobbies, Value, and Community

Let’s return to the accusation that when we donate to traditional charities, we’re indulging in a hobby and purchasing warm fuzzies.7 As it happens, the EAs are right: NG is fun, gives our lives meaning, makes us kinder, and brings communities together. Think of the festive camaraderie of walkathons, the ice bucket challenge, or the polar plunge; or the warm hospitality at food pantries and in soup kitchens; or the can-do spirit of religious and community groups pitching in during a crisis; or the friendly chit-chat (and dog-petting) when a passerby gives a pandhandler her spare change; or the remarkable achievement of the man who recently completed his mission of running a marathon every day for a year to raise over £1 million for a local cancer center and hospice. These experiences have value, even if that value can’t be quantitatively measured.

I know whereof I speak: Back when I was not so old and creaky, I ran three half marathons with a team of parents to raise money for Cure CMD, an organization that seeks cures for the rare muscular dystrophies that afflict our kids. One year our ragtag group raised enough money to fund a full-time researcher for an entire year. This accomplishment, the financial and emotional support from family and friends, the people I met, and the experiences we shared meant the world to me. I reject the EA belief that we are wasting our time and money when we help people close to us. It is important to relieve suffering in impoverished countries, but it is only human to want to care for our own families and communities too—and if we have fun along the way, all the better!

Finding Balance

So my beef isn’t with EA per se, but rather with the movement’s contention that they’re the only effective way of repairing the world. In fact the best EA charities share many similarities with the best traditional charities. They all focus on underserved and tractable problems, make donations go as far as possible, and test their interventions for effectiveness. Here are a few examples:

Give Well is an EA charity that makes cost-effective and evidence-based interventions in the developing world, including the treatment and prevention of malaria and nutrition assistance for children.

RIP Medical Debt has a simple and important mission: It purchases US medical debt at a steep discount and then frees people from its burden. A $100 donation relieves $10,000 in debt.

Unchained At Last was founded by my friend Fraidy. Herself a survivor of forced marriage, Fraidy and her organization provide legal and financial help so that women can escape forced marriage. In addition, Unchained is campaigning to make child marriage illegal nationwide. When Fraidy began her work, child marriage was legal in every state, and there was no minimum age of marriage; hundreds of thousands of children, including children younger than twelve, had been forced into marriage. Today, thanks to Fraidy and the team at Unchained, child marriage is illegal in seven states and two territories.

Yes, we ought to be clear-headed—but also open-hearted. As Tolstoy says in his parable “The Three Questions,”

There is only one important time, and that time is now. The most important one is always the one you are with. And the most important thing to do is to do good for the one who is standing at your side.

How about you, readers? Do you have any charities you’d like to recommend? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Speaking of charity, I enjoy periodically running charity contests, in which I pose a question or set up a challenge, and the winner gets a donation from me to a charity of their choice. Let’s try it here! I took the photo below in Lauterbrunnen, in the Swiss Alps. The reader who comes up with the best caption for this photo will win a $100 donation from me to your favorite charity. Good luck!

You may be objecting that Normal Generosity is an unfairly partisan name, but I would counter that the name Effective Altruism is also partisan, implying as it does that other forms of charity are ineffective. If the EAs are allowed a tendentious name for their movement, it’s only fair that the rest of us get one too.

As just one example, I once read a comment thread to an Astral Codex Ten post about targeted drug treatments for cancer. One commenter mentioned that his wife had stage 4 colon cancer. In the several dozen responses, not a single person said anything like, “Gee that’s rough. I’m really sorry.” Can you imagine that happening in any other community?

The Technopoptimism blog has an amusing take-down of this idea.

Good riddance. College-application essays favor affluent applicants, who can afford essay coaches and who have time to pad their resumes with extracurriculars that they can discuss in the essays. As I have written before, I think elite college admissions should be done by lottery.

And anyway, I would argue that EA is a hobby too: EAs enjoy crunching numbers, studying data, and talking about EA at conferences and in their many online forums. And while we may be purchasing warm fuzzies, EAs are purchasing intellectual clout.

First, danke for the plug.

Second, I enjoyed this. It articulates well a lot of my problems with EA and the rationalist movement - two things I should note that I'm actually broadly sympathetic to and actually do have a lot of value, even if I am uncomfortable with a lot of the particulars.

At the risk of filling your comments section with too many words, I'll boil them down to this. Long before Scam Bankman Fried I found the earn to give concept troubling for a simple reason: I've read history. I know the selling of indulgences when I see it. No one is more susceptible to religion than the devoutly irreligious.

But my overall difficulty with the rationalist movement is the simple truth that it doesn't matter how smart you are if you're not as smart as you think you are.

"SBF, for example, donated millions to candidates on both sides of the aisle, essentially canceling out his donations’ impact..."

I think the SBF political donations were not so much about helping any particular politician win re-election—more like getting politicians and PACs (on either side of the aisle) to support legislation that was favorable to SBF's crypto empire. His $40 million for Democrats is a matter of record; he says he contributed a similar amount to Republicans in "dark" money, and he did that because "reporters freak the f___ out" (SBF quote) when anyone donates to Republicans.

So really, if SBF was attracting investors to Bitcoin by appealing to EA sentiments, what was actually happening is that their investments were buying political favors that made Bitcoin more profitable. Which, I guess, in a roundabout way would make more money available for SBF's EA ventures. In theory.

A cynic might look at all this and imagine that all this EA stuff was a marketing ploy—not that some substantial chunk of investor money didn't go to EA and do some charitable good, but that a much more substantial chunk went to political graft and funding lifestyles of the rich and famous.

Anyway, great post. I always think of something my mother used to say: "Charity begins at home". I have a general distrust of large, remote charitable institutions with lots of overhead, even as I recognize that all of them are having some degree of positive effect. It is the nature of institutions and the humans who operate them to eventually prioritize self-dealing.

So, I donate money and time to local things.