"Nothing So Aggravates an Earnest Person as a Passive Resistance"

"Bartleby, the Scrivener" Book Club, Part 1

Welcome to the second annual Happy Wanderer summer book club! (If you are interested in last year’s book club, on Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, you can find our discussions here and here.) If you haven’t read this year’s choice, “Bartleby, the Scrivener” (1853), by Herman Melville, you still have time to read it for next week. You can find a free version of the story here. But even if you haven’t read the story, I encourage you to join our discussion!

This week, I will provide some background to the story—a plot summary, biographical sketch of Melville, and explanations of some potentially unfamiliar terms and historical context1—and leave the discussion up to you. Next week, I’ll offer some ideas of my own. Thank you in advance for participating, and I’m looking forward to hearing your thoughts!

“Ah, Bartleby! Ah, Humanity!”: A Plot Summary

The story’s unnamed Narrator is a lawyer who is “filled with a profound conviction that the easiest way of life is the best.”2 Accordingly, instead of trying cases in court, he “does a snug business among rich men’s bonds, and mortgages, and title-deeds.” When the story opens, the Narrator has three employees who copy legal documents and assist with other office duties: Turkey, who is a good worker in the mornings but then gets drunk at lunch and is useless in the afternoon; Nippers, who is dyspeptic and grouchy in the morning but productive after lunch (Nippers also runs a side business out of the office, arranging bail for some shady characters); and Ginger Nut, a twelve-year-old boy, who is in theory an apprentice but in practice spends most of his time obtaining ginger-nut cakes for Turkey and Nippers.

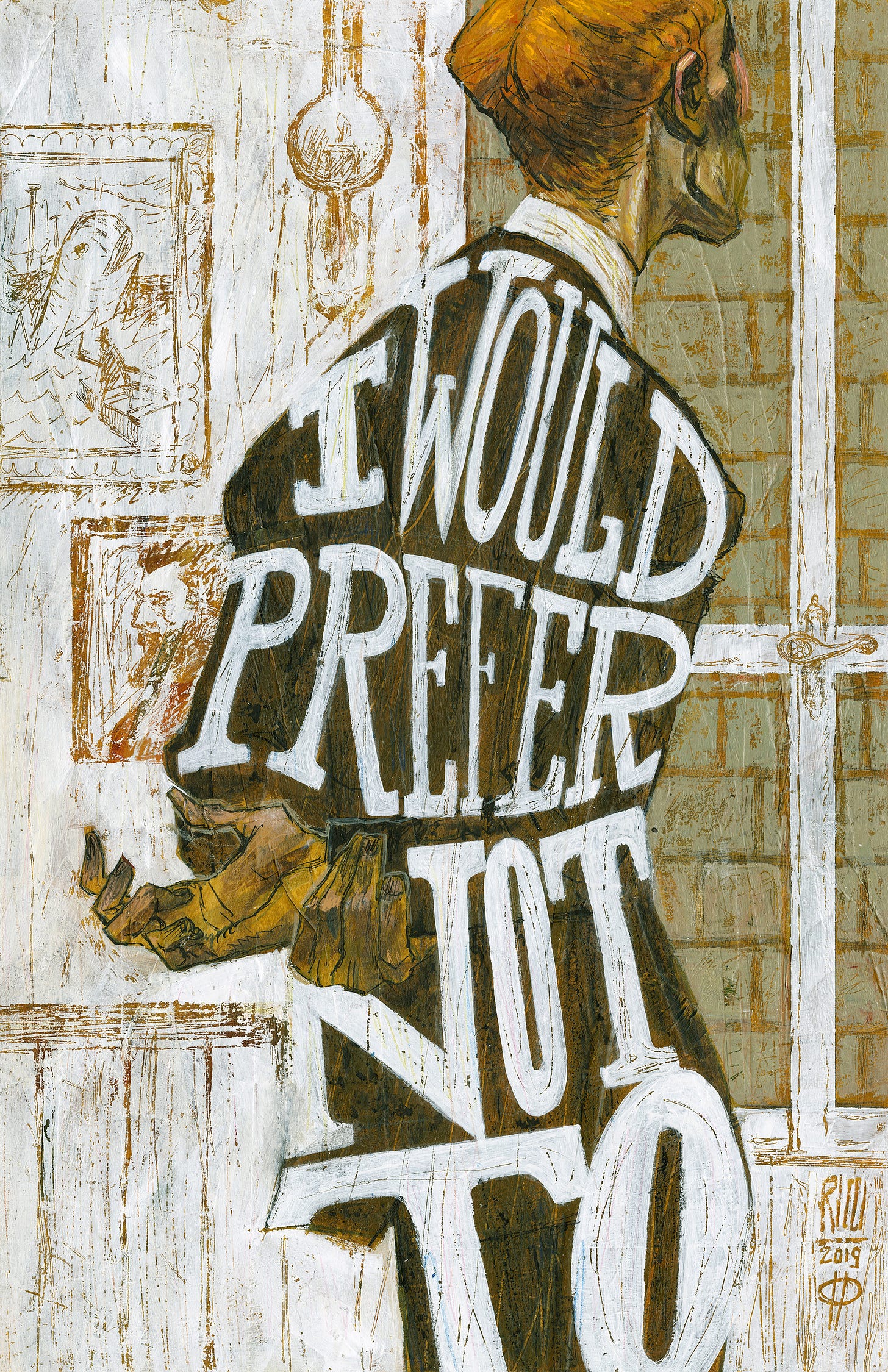

After the Narrator receives a lucrative sinecure, he needs additional help with copying documents, and so he hires Bartleby, “a motionless young man . . . pallidly neat, pitiably respectable, incurably forlorn!” For the first several days Bartleby is an astonishingly speedy and diligent worker, but one day the Narrator asks him to help compare documents, and Bartleby responds, “I would prefer not to.”

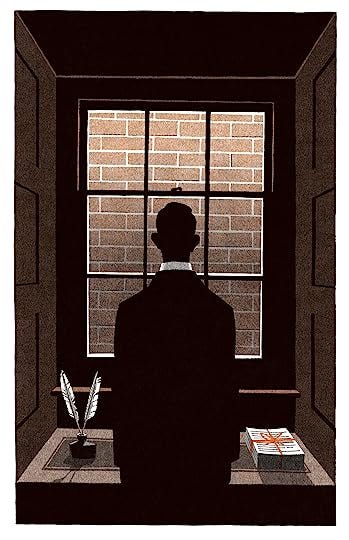

To the Narrator’s chagrin, Bartleby would prefer not to perform any task that requires him to interact with other people. The Narrator feels powerless in the face of Bartleby’s passive resistance. Bartleby eventually stops scrivening altogether and spends his days in “dead-wall reveries,” staring at the brick wall directly outside his window.

One Sunday, the Narrator stops by his office and comes upon Bartleby there, “in a strangely tattered déshabillé”; in fact Bartleby is living in the office. The Narrator attempts to pay Bartleby off so that he will leave, but Bartleby remains. Finally, the Narrator, worried about “a whisper of wonder [that] was running around, having reference to the strange creature I kept at my office,” moves his office to a new building, leaving Bartleby behind.

The Narrator makes one final attempt to help Bartleby, asking him, “will you go home with me now—not to my office, but my dwelling—and remain there till we can conclude upon some convenient arrangement for you at our leisure? Come, let us start now, right away.” But Bartleby replies that “at present I would prefer not to make any change at all.” The Narrator later learns that the building’s owner has had Bartleby arrested for vagrancy. He visits Bartleby in the Tombs, where he “found him there, standing all alone in the quietest of the yards, his face towards a high wall, while all around, from the narrow slits of the jail windows, I thought I saw peering out upon him the eyes of murderers and thieves.” The Narrator pays the jail’s cook to supply Bartleby with good meals, but Bartleby refuses to eat.

The Narrator returns to the Tombs a few days later to find Bartleby’s dead body in a high-walled courtyard, “strangely huddled at the base of the wall, his knees drawn up, and lying on his side, his head touching the cold stones.” A brief coda, which the Narrator offers as a possible explanation of what ailed Bartleby, reveals that before Bartleby came to the Narrator’s chambers, he had worked in a dead-letter office:

Conceive a man by nature and misfortune prone to a pallid hopelessness, can any business seem more fitted to heighten it than that of continually handling these dead letters, and assorting them for the flames? . . . pardon for those who died despairing; hope for those who died unhoping; good tidings for those who died stifled by unrelieved calamities. On errands of life, these letters speed to death.

“Misery Hides Aloof, So We Deem That Misery There Is None”: A Biographical Sketch of Herman Melville

Herman Melville (1819–91) was born into an aristocratic family; his two grandfathers were heroes of the American Revolution. He enjoyed a luxurious childhood, but his father died young after making a series of bad investments, leaving the family deep in debt, and demoting young Melville to the status of a pitied poor relation. Starting at age twelve (like Ginger Nut!), Melville took on a series of odd jobs to make money, and at age twenty-one he embarked for the South Seas on a whaling ship.

In the summer of 1842, Melville and a friend jumped ship in the Marquesas Islands and lived with an isolated tribe. He then joined an Australian whaling crew, took part in a mutiny, went to jail in Tahiti, explored Tahiti and later Hawaii, and finally sailed for home in the fall of 1844. Melville’s tremendously popular first two novels, Typee and Omoo, which recounted these South Seas adventures, brought him fame and fortune. Feeling optimistic about his future, Melville married Elizabeth Shaw in 1847.

At this point, Melville’s fortunes took a turn for the worse. He wanted to write great literature for the “eagle-eyed,” not adventure stories for “the mob.” The public, expecting more adventure stories, felt betrayed and rejected his next few novels, including Moby-Dick (1851). By the time Moby-Dick came out, Melville had to support his mother, sister, wife, and young son on no income, and the family fell deeply into debt. Even worse, Melville’s next novel, Pierre (1852), was so bizarre3 that people, including even his family, began to suspect that he was going insane. (His family went so far as to arrange a consultation with the eminent Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes.) It is at this point that Melville wrote a series of short stories, including “Bartleby, the Scrivener,” which he published anonymously in literary magazines. To supplement the small income these stories brought in, Melville obtained a job as a customs inspector.

Melville’s later life was marked by personal tragedies, including the suicide of his oldest son and an estrangement from his second son. But in his final years, he began to enjoy a revival of his reputation. While he didn’t live to see himself lauded as one of the greatest writers in America—and indeed in the world—he did at least experience glimmerings of the posthumous fame he would enjoy.

A Brief Explainer of Terms, Context, and Allusions

John Jacob Astor: John Jacob Astor (1762–1848) was the founder of one of the richest dynasties in America and was America’s first multimillionaire. He made his fortune through fur-trading, opium-smuggling, and real estate. While the Narrator claims he was “not unemployed in my profession by” Astor, it is highly unlikely that Astor would use the services of such a small-timer as the Narrator.

Master in Chancery: A coveted patronage position that came with a guaranteed income. The Narrator is understandably upset that New York changed its constitution to eliminate such sinecures—and the money that came with them.

The Tombs: A nickname for New York City’s notoriously terrible jail.

Passive resistance: Melville may be referring to “Resistance to Civil Government,” by Henry David Thoreau, which came out four years before “Bartleby” was published.

Red tape: I recently learned that we refer to bureaucratic hurdles as red tape because offices used to bind up sheafs of documents with actual red tape, as the Narrator does in the story.

Trinity Church: A beautiful Gothic-revival cathedral near Wall Street. In Melville’s time, the church was associated with the upper classes, and John Jacob Astor was one of its most celebrated patrons.

Petra: An ancient city, carved into stone cliffs, on the Silk Road. Petra was once a center for trade but has been deserted for centuries.

Marius at the ruins of Carthage: Caius Marius was a Roman general who was exiled for his excessive ambition. Carthage is a North African city that was destroyed by the Romans. As this site notes, “The fate of Marius has been compared with that of the painter’s patron, Aaron Burr, whose fortunes changed dramatically after he killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel and was tried for treason.”

Adams and Colt: The Narrator is referring to a notorious murder that occurred while Melville was at sea. The Narrator has his own reasons for sympathizing with Colt, but in fact Colt was guilty: Adams came to Colt’s office in an attempt to collect a debt, and Colt (the brother of the inventor of the revolver) shot him dead. Colt was arrested, convicted, and sentenced to death, but he killed himself before the sentence could be carried out.

“Edwards on the Will” and “Priestley on Necessity”: These tracts by the Puritan minister Jonathan Edwards and the scientist Joseph Priestly both argue that there is no such thing as free will.

Monroe Edwards: Edwards was a financier who was convicted of forgery and embezzlement. His crimes were so extreme that they temporarily undermined trust in the stock market.

Asleep “with kings and counselors”: The full quote, in which Job laments his misfortune, reads “For now I would be lying down in peace; I would be asleep and at rest with kings and rulers of the earth, who built for themselves places now lying in ruins” (Job 3:13–14).

Questions for Discussion

How does this story make you feel? Why does it make you feel that way?

The Narrator comments that “Nothing so aggravates an earnest person as a passive resistance.” How might you explain Bartleby’s behavior? The Narrator’s response?

Have you ever worked in an environment like the Narrator’s office? What insights does Melville’s work world have for our own?

What would you do if Bartleby were your employee, or even just someone you knew?

The story is full of symbols—walls, bonds, the dead letter. What point is Melville making through these symbols? What other symbols did you notice?

What did you like best about the story? What are some quotes you especially loved?

Did you keep count of how many times Bartleby said some version of “I would prefer not to”?

How about you, readers? What are your questions and insights about the story? What did you find particularly interesting or moving? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

There are far more Moby-Dick cartoons out there than Bartleby ones. This article includes several droll examples; my favorite is this one:

But I did manage to find one good Bartleby cartoon for you all:

Unless otherwise indicated, the source for the biographical and historical information in this post is The Norton Anthology of American Literature, Shorter Fourth Edition, ed. Nina Baym, Wayne Franklin, Ronald Gottesman, Laurence B. Holland, David Kalstone, Arnold Krupa, Francis Murphy, Hershel Parker, William H. Pritchard, and Patricia B. Wallace. (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1995). I have to chuckle: This “shorter” edition weighs in at more than 2700 pages!

This and all quotations are taken from the edition I used in college, Herman Melville: Selected Tales and Poems, ed. Richard Chase (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1950). Incidentally, I am old, but not so old that I went to college in 1950! I don’t know why my professor chose this edition instead of a more recent one.

I read it for a class in graduate school. Pierre is indeed a very strange book, about brother-sister incest, violence, and other unsavory topics.

I really enjoyed reading this short story. I love Melville's style. I got a good laugh when the narrator had the idea of just "assuming" Bartleby wasn't there, walking up to his office and running into him "as if he were air", and then somehow Bartleby would finally leave after this because, "it was hardly possible that Bartleby could withstand such an application of the doctrine of assumptions." That is pure gold.

More seriously though, I think the central dilemma that struck me in the story is, "how far do we extend decency and compassion to those who fall outside the norms of society or harm us?" The narrator deals with this question in a number of ways. He talks about whether the troubles brought on him by Bartleby were "predestined from eternity" and "for some mysterious purpose by an all-wise providence." He assumes a "wise and blessed frame of mind" that takes for granted that he is serving a higher purpose of charity by sheltering Bartleby from the world. He makes the observation that I have found to be true in my life: "Aside from higher considerations, charity often operates as a vastly wise and prudent principle—a great safeguard to its possessor."

As the narrator grapples with how much his common humanity entitles him to help Bartleby from the moral standpoint, he is slowly dragged back to more self-interested actions by the gossip of his professional peers and the suffering of his reputation. This I think is Melville's way of pointing out how the opinion of the masses corrupts us, and how we often are more wise and better people when we think for ourselves. Truly, Bartleby places demands on the narrator that are far beyond what anyone should be expected to bear. And yet there is something admirable about how far he goes to help his common man, and a definite sense of loss when he finally abandons Bartleby.

Overall it was short, thought-provoking, and entertaining. Great book club pick!

Love the Bartleby cartoon! I remember watching a PBS version of "Bartleby" in high school and they made the story very funny. His death at the end is absurd and ironic, not tragic. Many years later I read the story and found it very sad. Still, though, the phrase "I would prefer not to," makes me laugh, even though it's not funny in the context of the written story. Nice summary and notes--thanks, Mari.