PE Stands for Public Education

Warning: Discusses the Presidential Physical Fitness Test and [shudder] Rope-Climbing

Ever since moving to Switzerland, I have been engaged in a quixotic project—to hike to the summits of as many mountains as I can. In order for a hike to count as a summit, the mountain must rise at least 300m/1000ft above the land that surrounds it (this meets the scientific definition of a mountain), and I, in turn, must also rise, under my own power, at least 300m/1000ft in altitude. A few weeks ago I hiked to the summit of a mountain for the twenty-first time.

In addition to hiking, throughout my life I have enjoyed biking, running—I have run three half-marathons—weight-training, yoga, and even trampoline-jumping (in a cardio class at my old gym). Exercise is a necessity for me, which is why you will be surprised to learn that as a child I feared, dreaded, nay loathed, PE.

What went wrong? How could a kid who loved being active and running around outside in nature also get an anxious stomach every day before PE? Well, our PE classes were neither useful nor enjoyable for me. About half the time we practiced sports skills most of us would never use. Instead of exercising, we stood around in line waiting to hit (or in my case miss) a softball or to toss the ball in the basket (or in my case to miss). Or we would be required to perform feats of strength in front of everyone. For instance, rope-climbing. Why was rope-climbing ever even a thing? What purpose was served by making us scramble up a rope (and yes, some of us were wearing dresses on those days and didn’t appreciate having to expose our underwear to the boys) all the way to the 20-foot ceiling, with only a thin mat to catch us if we fell? Did the Board of Education think we were going to be pirates one day?

A Brief Digression about the Most Dangerous Game

When we weren’t waiting around to demonstrate that we could (or couldn’t) hit, kick, and throw balls, we were unleashed to play unsupervised games. Pace the classic story by Richard Connell, the most dangerous game is not man but pinball, which haunted my PE classes and nightmares alike. Remember those hard rubber gym balls?

Pinball was dodgeball on steroids: In addition to the usual dodgeball rules, in pinball each team had three pins at its end of the gym, and once they were all knocked over, your team would lose. Many of the boys in my class were great at pinball and darted around the court with speed and grace as they threw and caught the balls, but most of the girls (for once not just me) weren’t good at the game at all, and so our job was to serve as human shields for the pins. We would huddle around the pins and prepare to be hit by those hard balls thrown at top speed. I am such a nerd that I once occupied myself while guarding a pin by trying to calculate the velocity of the ball as it was hurled at us by the strongest boy in our class. Suffice it to say that is easy to imagine personal-injury lawyers having a field day1 with this game nowadays.

My guess is that because you have willingly signed up to receive my long articles every week, you are on my end of the nerdy-to-sporty spectrum, so maybe you can relate to this post. The problems I experienced in PE—the useless tasks, my inability to learn, and the humiliating testing—are the same problems other kids face in their academic classes because of theories about education promulgated by politicians, academic theorists, and test-making companies.2 We need to return to the wisdom of classroom teachers, who know from their practical experience the best ways to make kids happy and successful lifelong learners.

Lessons from PE for Public Education

As is true in PE, so too in education in general, we need to be sure we’re teaching kids the skills they will need for the future. My PE classes put an inordinate focus on skills for particular sports that only a few people continue to play after graduation. How many adults still play volleyball on a regular basis, for instance?3 Wouldn’t it make more sense for PE to focus on activities that will help students to remain healthy throughout their lives, such as stretching, balance exercises, running, hiking, biking, and swimming? And yes, I acknowledge my bias—these all happen to be activities I enjoy. But I would bet that I’m not alone, and that more people go on weekend hikes and bike rides than play volleyball.

Similarly, we have begun to have conversations about what should be in the US math curriculum in order to best prepare students for the future. The US math curriculum currently builds toward calculus, and students feel strong pressure to take it in order to get into selective colleges. In addition, most high school students are expected to pass algebra 2 in order to graduate. This requirement is a mismatch with the workplace, because very few careers require calculus or even algebra 2. We know this from a survey conducted by Freakonomics, a podcast with a highly-educated audience in which people with quantitative skills are over-represented. The survey asked whether respondents used algebra 2 and calculus in their work or home lives. The result? Only 2 percent of respondents ever used calculus, and only 12 percent used algebra 2. A number of mathematicians are now arguing that while US high schools should retain algebra 2 and calculus as electives for students who have strong interest and ability in mathematics, the required curriculum should focus on subjects that students need to become educated, critical thinkers—for example, trigonometry (important for careers in the trades), statistics, and data science. My high school allowed students who were not interested in STEM careers to graduate having taken algebra 1 in ninth grade plus a semester course called Consumer Math, which taught about compound interest, debt, taxes, budgeting, and bookkeeping. I think all students should take Consumer Math!

A second lesson PE teaches for public education is that many kids don’t pick up skills and topics intuitively but need to have the task broken down into steps, which they can then practice. When I was a kid, I would have LOVED it if a teacher had shown me, step-by-step, how to throw a softball. I didn’t enjoy looking so awkward in front of everyone! Or consider the method for learning to do pushups in this video. Hampton Liu shows how to do each component of a pushup safely and offers adaptations for those of us who can’t perform a full pushup, to help us build up muscle strength. And then he praises us for small successes along the way. Unless we have extraordinary talent, this is how we all learn.

We see the same issue in the debate over whether reading should be taught using the whole language or the phonics approach. The whole language approach to reading instruction, which was developed in schools of education and was popular until fairly recently, assumes that children have a natural aptitude for learning to read, and that if you give children vivid, interesting stories, they will learn to read on their own. This is in fact how I did learn to read, when I was three. But expecting all children to learn to read the way I did makes no more sense than expecting me to learn to throw by just putting a softball in my hand and saying “throw this.” Here is a recent article about an education guru who persuaded a generation of teachers to use “balanced literacy” (primarily whole language) and who is only now acknowledging the evidence that that approach doesn’t work for most kids. (A similar approach to reading instruction that is currently used nationwide, Reading Recovery, has recently been discredited too.) Phonics, by contrast, teaches children to connect the sounds they hear with letter combinations they see. Children learn to put the components of words together, so that they are able to sound out unfamiliar words. Most classroom teachers now teach phonics and use whole language only when appropriate for particular children. This mixed approach gives children access to interesting stories as well as the tools to decode them.

The same goes for learning arithmetic, incidentally. The Common Core math curriculum doesn’t teach young children the standard algorithm for addition (the way we all learned to add) until fourth grade. Instead, Common Core requires children to experiment with various alternate strategies for each problem, in an effort to get students to develop a “number sense.” However, very few young children are capable of such abstract thinking. Most elementary-school teachers will tell you that children need to learn to do arithmetic through algorithms first. Children will have an easier time learning more abstract concepts later, as their brains mature. And while the Common Core curriculum doesn’t set aside class time for memorizing multiplication tables, any classroom teacher will tell you that it is crucial that children memorize their times tables in order to master more challenging math later on.

Third, testing is not the same thing as teaching, and sometimes testing even impedes learning. A couple of generations of US kids underwent the Presidential Physical Fitness Test (PPFT)—which has been called “bizarre and sadistic”—before it was finally discontinued in 2012. President Eisenhower inaugurated the PPFT because he was ashamed of how out of shape American kids were when compared with Swiss children. Politicians worried that Americans were unfit for military service, so they developed a testing regimen that emphasized the kind of fitness that young men of that era would need in order to become soldiers—for example upper-body strength (pull-ups and sit-ups while holding a weight on your belly) and speed and agility (the shuttle run)—rather than exercises that encourage lifelong health and an active lifestyle (the hiking and climbing that the Swiss kids did). As a child I had weak muscles but also a strong feminist sensibility, and I thought it was unfair that the PPFT tested physical capacities more typical of boys than of girls, especially since more “female” physical aptitudes like endurance and flexibility are crucial for lifelong fitness and injury prevention. This podcast episode is an enormously fun takedown of the PPFT.4

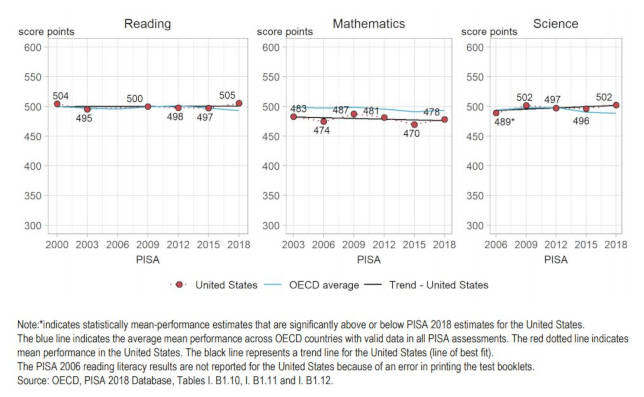

The mere act of testing students does not make them able to master a task. For sports and academics alike, students who aren’t already gifted need instruction, coaching, encouragement, and practice. I did not magically become able to do the bent-arm hang because I was forced to attempt it in front of the whole class every spring, any more than a child struggling with arithmetic suddenly becomes adept because s/he has been subjected to standardized testing. The PPFT failed in its effort to produce young adults who were fit enough for the military; the proportion of young Americans who are qualified for the army has dropped by almost 50 percent since 1950. Similarly, programs that attempt to improve students’ academic learning through high-stakes testing, such as Common Core, don’t work. The PISA scores of US students have stayed flat since the introduction of Common Core in 2010.

It shouldn’t surprise us that testing has made students neither more physically fit nor more academically successful, because high-stakes testing can impede learning. The tests take up valuable class time and cost school districts $1.7 billion per year, money that could be better spent on instruction. They also incentivize schools to focus on math and reading to the exclusion of other subjects that students enjoy, such as science, history, art, and music. High-stakes tests are stressful and unpleasant for students and teachers alike. And while some people enjoy competition and are inspired to work harder so they can win a game, beat a standard, or achieve a high score, many people (like me) prefer noncompetitive activities and working toward goals we set for ourselves (like my summits challenge). Some of us do better with praise and encouragement along the way than with the potential reward of victory after a competition; some of us thrive when we collaborate with each other or work independently toward our own goals. The PPFT and high-stakes standardized tests are good motivators for competitive types, but they put off students who would do better with noncompetitive challenges.

In Praise of a Great PE Teacher

A humiliating and useless regimen of testing and failure is not inevitable, and, taught properly, PE can inspire and engage students regardless of their innate gifts. I would like to end with a tribute to Mr. M, the wonderful PE teacher at my kids’ elementary school. My daughter is disabled; she is able to walk with a cane, but not for long distances, and she can’t run, bike, or climb stairs. Remembering my own experiences as a child, I was worried about what PE would be like for her, but Mr. M created a special program for her—he exempted her from many activities and adapted the rest in every class for five years. Even better, he gave her top marks on her report card (“making exceptional progress”) because, as he told me when I stopped by to thank him, “she works as hard as anyone in the class.”

The PE year culminated in field day, which thanks to Mr. M was a festival of silliness. Although field day did have a couple of competitive activities like tug-of-war, kids also enjoyed the rubber-chicken relay race—where you run with a rubber chicken between your knees—a water-balloon toss, and several other activities whose goal was not winning but having fun. Mr. M wanted to show kids that fitness is a lifelong pleasure, so he invited parents to help out and even participate. He also recruited the high school baseball and softball teams to supervise and be role models for the younger kids at each station. I think we should have the same goal for public education as Mr. M had for PE: To teach children to do their best, to honor their different abilities, and to foster lifelong learning.

What do you think, readers? Did you love or hate PE? And why? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Speaking of pirates, here is one of my all-time favorite New Yorker cartoons:

Or here is a fun joke you can try on the kids in your life:

First, you ask, “What is a pirate’s favorite letter?”

Then the kid will say, “Arrrrrrh!” [R]

Then you say, “You would think that, but in fact [say this in a pirate voice] he loves the sea [C] best of all!”

Tee hee! Or how about this idea?

You see what I did there?

Another issue, which is beyond the scope of this article and will get a post of its own in the future, is tracking.

I admit to having a grudge against volleyball. I was a dedicated pianist in high school and didn’t appreciate it when volleyball-incurred finger injuries interfered with my practicing. My son, who shares my opinion, refers to volleyball as “corporal punishment ball.”

In the interest of fairness, I would like to share one nice story from the PPFT. When I was in high school, a boy in our class, Shawn, could walk on his hands and even go up and down stairs. One of the tested skills on the PPFT that year was handstands, and so after the rest of us ungainly types flopped around unsuccessfully, we eagerly awaited Shawn’s turn. We watched in amazement and cheered him on as he stayed upside-down for the last several minutes of class. He was still going strong at the end of class, so the teachers let him stay behind, just to see how long he could hold the handstand. He stayed in a handstand for more than half an hour!

I don’t know that I hated P.E., but I was never very good at it. I’m not sure if I even passed all of those Presidential Fitness tests! And I LOVE the video teaching us how to learn and succeed at pushups! I’m going to do that! Thank you. 🙏🏽

I hate the presidential fitness tests!! My high school used the scores for actual grades which went on my report card, bringing down my GPA. I’ve never done a pull up successfully in my life, and I used to get negative numbers on the sit and reach because of how my spine is curved. I am still so bitter!