Plot Twist

What We Learn When Stories Surprise Us

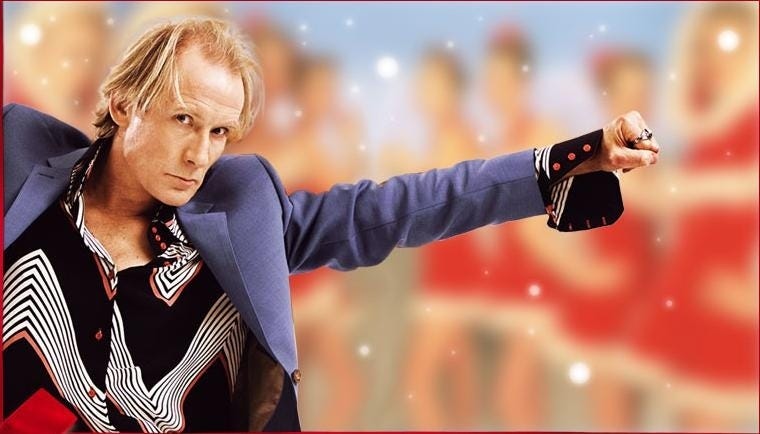

Warning: As befits an article about plot twists, there will be spoilers here. However, all but one of the stories discussed below has been out in the world for years if not decades, so hopefully readers are already fully aware of these plot twists. The sole exception, Living, came out last year. The Living spoilers are in the final section, below the photo of Bill Nighy, so readers who don’t want spoilers should skip this section.

Who doesn’t love a good plot twist? It’s fun to be shocked by something we didn’t expect and then to go back over the story, searching for hints of the surprise to come, or—if we know in advance that there will be a twist—to try to figure it out ahead of time. Probably the most famous plot twist in recent years comes at the end of The Sixth Sense (1999). A sharp-eyed friend of mine guessed the twist because Bruce Willis wore the same clothes through the whole film, but the movie fooled pretty much everyone else in the country.

I figured out another famous plot twist, in The Crying Game (1992), because Dil, the character played by Jaye Davidson, sings during the film. My experience as a classical singer and early-music enthusiast helped me to recognize that the actor was not an alto but a countertenor. But, judging by the reaction of the audience around me at the big reveal, I was the only one who had guessed the secret. Most plot twists are like this—fun on their own but without a special message. By contrast, in some rare but affecting cases, a story surprises us and helps us learn something valuable about ourselves and our society.

Lone Wolves, Alpha Wolves, and a Better Way to Be a Man

Cameron Crowe’s first film, Say Anything (1989), may be the reason that it is obligatory for straight white Gen X women to have once had a crush on John Cusack. Hey, I don’t make the rules. I mean:

To paraphrase the opening sentence of Emma, “Diane Court, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, had lived eighteen years with very little to distress or vex her.” And then her unlikely Mr. Knightley, Lloyd Dobler, an underachieving army brat who aspires to become, of all things, a professional kickboxer, invites her to their graduation party, and they fall in love. A couple of obstacles stand in the way of their happy ending: Diane’s doting father does NOT approve of Lloyd (more on this below), and Diane has won a prestigious scholarship and will be leaving for the UK at the end of the summer.

The solution to their dilemma might seem obvious now, but when the film first came out, it was simply unimaginable that a young man would give up his career plans—however inchoate and unrealistic—for his girlfriend. Popular romantic comedies of the past would culminate in the woman happily giving up her career for love, marriage, and kids—or sadly pining after the lone wolf as he strides off into the sunset and onto his next adventure. Or the more “progressive” films would end with the two lovers wistfully parting so that the man and the woman could continue independently in their own lives—for example, just off the top of my head, Roman Holiday (1953), The Way We Were (1973), Witness (1985), La La Land (2016), and A Star Is Born (1937, 1954, 1976, 2018).

It wasn’t just in the movies either. I was in my early twenties when Say Anything came out, and every couple I knew broke up after graduation because the two partners were headed to different cities for grad school or careers, and it was considered totally unacceptable to compromise career goals for love. The unprecedented plot twist in Say Anything is that it could be praiseworthy to sacrifice ambition for a relationship and, even more radically, that it could be the man instead of the woman who makes the sacrifice.

The film has a plot twist connected to social class as well. Diane’s father, Jim, thinks that Lloyd is a lowlife who will destroy his daughter’s prospects. The irony is that in spite of his respectable upper-middle-class position, it is Jim who is the lowlife, and a criminal too: He steals from the seniors who live in the retirement homes he owns, ostensibly to build up a nest egg for Diane. But Diane, understandably, doesn’t want his dirty money. After Jim goes to prison, Lloyd’s sister,1 herself a victim of a lone wolf ex-husband who has abandoned her and her kids, persuades Lloyd to “be a man.” Lloyd visits Jim in prison to tell him that he loves Diane and is staying with her. In contrast to the idea of manhood that is too prevalent in our culture, of the alpha wolf who, like Jim, dominates and exploits others in order to succeed, Lloyd shows us that a better way to be a man is to be honest, to act honorably, and to put other people first sometimes.

Even When It’s Difficult, We Should Try to Forgive

A friend posted a video on Facebook in 2014, and it has stayed with me ever since. The video begins with Robert Downey Jr. giving a speech at an awards ceremony in Los Angeles. He talks honestly about his struggles with addiction, how he hit rock bottom and went to prison but made a successful recovery with the help of friends, and how grateful he is for the forgiveness that people have granted him. He has the audience eating out of his hand and showering him in applause and good will. And then comes the plot twist, which we can see in the video below. Downey isn’t asking the audience to forgive him. It’s easy to forgive extremely successful, charismatic people who have turned their lives around and whom we already liked anyway. Downey is talking about something much more difficult: Forgiving Mel Gibson.

Make no mistake: Mel Gibson has done some terrible things. He was convicted of drunk driving and pleaded no contest2 to charges of domestic abuse against his second wife. He has said truly awful things about Jews, Black people, and homosexuality. His 2004 film, The Passion of the Christ, trades in antisemitic tropes. When the police stopped him for drunk driving in 2006, he launched into an antisemitic tirade that provoked Hollywood to blacklist him for several years.

Downey gave his speech to persuade Hollywood to bring Gibson back into the fold. He invoked Jesus’s immortal words “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone” and alluded to the Jewish High Holidays (which had taken place in the two weeks before the speech) to remind his audience that the Judeo-Christian tradition requires that we forgive those who sincerely repent. It is interesting to watch the audience’s reaction to this speech. People are hesitant at first, but Downey wins them over.

Am I saying that we should always forgive? Not at all. I recently read Women Talking, by Miriam Toews. The novel and the 2022 film by Sarah Polley are based on a series of crimes that took place in the early 2000s in a small Mennonite colony in Bolivia. Over a period of several years, eight men drugged and raped more than a hundred women and girls ranging from ages three to sixty. The book and film begin at the moment when the men have gone into town to bail the rapists out of jail. The women know that when the men return, they will be forced to “forgive” their abusers. For the remainder of the story, the women debate what to do.3 I hope that most of us agree that this situation desecrates the idea of true forgiveness.

So was Hollywood right to forgive Mel Gibson? When we’re faced with the dilemma of whether to forgive someone, we ought to consider the severity of the offense as well as the sincerity of the repentance. I believe that Gibson passes both tests, and we are all better off now that he is again making films.4 While he continues to hold political views many of us might find reprehensible, in the years since Downey’s speech and since going into treatment for alcoholism, Gibson has not had any ugly outbursts or trouble with the police and has returned to filmmaking. His 2016 film, Hacksaw Ridge, tells the inspirational story of the first conscientious objector to receive the Medal of Honor, for saving the lives of seventy-five soldiers during his service as a medic at the Battle of Okinawa. At both the Golden Globes and the Academy Awards, the film was nominated for Best Picture, Gibson was nominated for Best Director, and Andrew Garfield was nominated for Best Actor.

We Should Make Our Time Here on Earth Count

I have loved Bill Nighy ever since he was (in my opinion; yours may differ) the one good thing about Love, Actually.

Living (2022) was written by Kazuo Ishiguro and is based on the 1952 Kurosawa film Ikiru. Rodney Williams, played by Nighy, is a buttoned-up bureaucrat who presides over an office of cowed workers. As an employee of the London city council, he ought in theory to support projects that help the community, but he and his workers obstruct progress by filing every citizen petition and complaint in enormous stacks of papers, never to be seen again. We soon discover that Williams is so subdued and repressed because he is still grieving for his wife, who died many years before the film opens. His relationship with his son is distantly cordial at best, while his daughter-in-law is barely civil to him. And then he learns that he has terminal cancer and has only a few months to live.

What will Williams do with his remaining time on earth? Conditioned as I was by Nighy’s role as Billy Mack, the rakish, ribald rock star who performs in the nude at the end of Love, Actually, I expected his role in Living to follow a similar chaotic and lusty trajectory. I expected the story would be like a typically optimistic American film and show him awakening into new life, indulging himself in worldly pleasures, fulfilling his bucket list, reconciling with family, and then bidding the world a heartfelt farewell, surrounded by loved ones.

In the days after his diagnosis, it does look like the story will go that way. Williams carouses in a bar at a seaside resort and befriends Miss Harris, a lovely, kindhearted young woman who used to work in his office. “Oh great,” I thought. “An old man brought back to life through a relationship with a young woman. Harumph.” But no, there is a plot twist: Miss Harris tells Williams that his attentions make her feel a bit uncomfortable, and Williams realizes that he has been relying on her to help him work through his fear and regret. He decides that instead of leaning on Miss Harris, he will help other people. He makes his last months of life count by taking on a small project, turning an abandoned courtyard filled with hazardous junk into a playground for the neighborhood’s children. This is is a Sisyphean undertaking. He must rebel against an oppressive system of obstructive bureaucracy. But because Williams was once a functionary in the system, he is just the man to defeat it.

And defeat it he does. At the end of the film we see Williams at night, alone in the playground he brought into being, gently rocking on a swing. His is a modest, quiet accomplishment, but it will mean the world to the children and the parents in the neighborhood. It is not self-indulgence or worldly success but rather good deeds and caring for others that make our lives worth living. As Ishiguro says,

I found this story about this man, who with a supreme effort, within the confines of the very restrictive world that he has to live in, and the confines of who he has become over the years, finds it within himself to turn it around. . . .

He just does things a little bit better, and that makes the crucial difference between his life being empty, a shallow life, and one that that is actually fulfilled and magnificent.

We are all capable of doing “things a little bit better” too.

How about you, readers? What is your favorite plot twist, in books, movies, or life? What did you learn from it? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

So, countertenors. I am not normally a fan of countertenors—their tone can be thin and muted or reedy and piercing rather than full and rich. Besides, as a mezzo-soprano, I resent that they take roles that could be sung by mezzos or altos. That being said, Bejun Mehta is extraordinary. I had the opportunity to see him perform in a recital in Prague, and his energy, joy, and virtuosity are thrilling to watch. Listen to his performance of “Sento la Gioia” (“I feel joy”), and I predict that you will agree!

Charmingly, Lloyd’s sister is played by Joan Cusack. John and Joan Cusack have appeared in several films together and often play siblings.

The charges were not substantiated, and Gibson says he took the plea, “which allowed [him] to end the case and still maintain [his] innocence,” to spare his children a lengthy, public trial. You can find this quote from Gibson in the Wikipedia article cited above.

This is not a spoiler, so please don’t be deterred from reading the book, which I recommend. (I haven’t seen the film but have heard good things about it.)

A brief digression: Gibson has said that when he made those horrible antisemitic remarks in 2006, he was trying to commit suicide by cop. Whether or not this is true, he was engaging in an act of self-destruction. In liberal circles, the surest way to cast oneself out of society utterly and irredeemably is to say bigoted things. It speaks well of the people in Hollywood that, thanks to Downey’s intervention, they took Gibson off the blacklist.

I'm glad you watched Living. It's excellent. Its emotions and its message of doing something materially good for others (even if it's something small like getting a playground built) have really stuck with me.

I wonder sometimes, how much good would people do in the world if they weren't so preoccupied with the appearance of Being Good on social media instead?

I also love a good plot twist. However, your column made me think of a different response to the idea of the man riding off into the sunset to follow his dreams while the woman remains, wistful and forlorn, on the farm (or wherever). Do you remember the Sylvia cartoons by Nicole Hollander? There's one were Sylvia is watching television and the dialogue bubble says, "Honey, I love you, but I've gotta be movin' on." Sylvia's comment: "Break his kneecaps." I've always loved that as a response to the "a man's gotta do what a man's gotta do" movie ending. And that would be quite a plot twist!