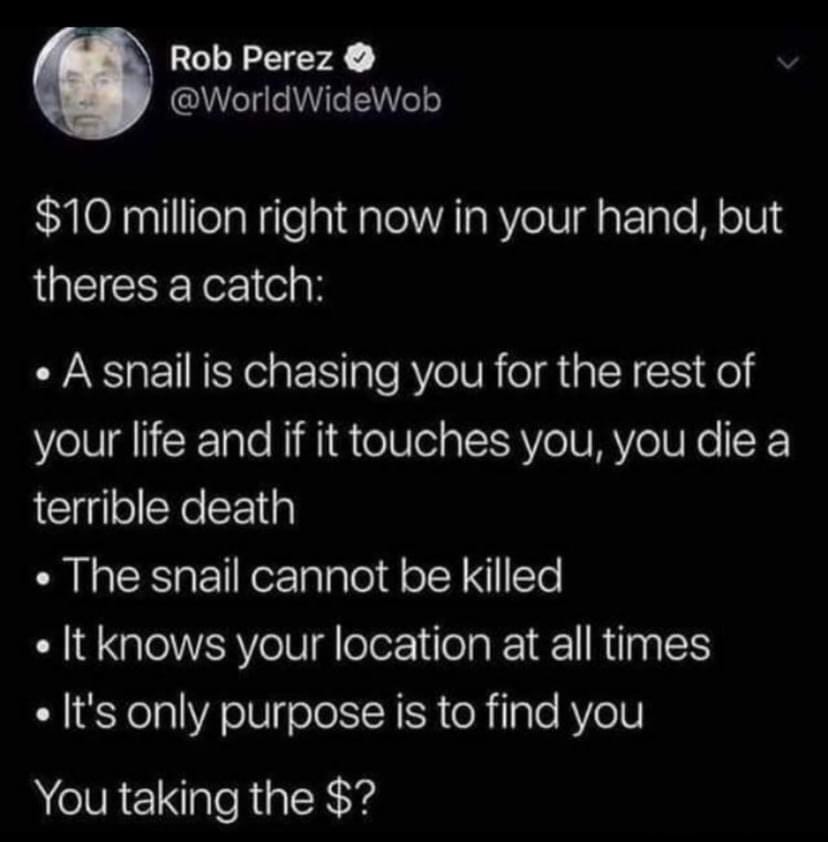

Let’s start with something silly. Readers, have you seen this dilemma? What would you do? Would you take the money?

This meme is trying to force us into zero-sum thinking: It wants us to believe that if we take the money, we and the snail are in a battle to the death, and only one of us can prevail.

But is this actually true? Read the meme again. The snail will kill us if it touches us, but its purpose is just to find us; the meme doesn’t say that the snail actually wants to kill us. It’s entirely possible to find a compromise here. We could say, “Hey snail, did you know that you will kill me if you touch me? So could you just not?” And the snail would say, “Oh wow! I had no idea! Of course! Now that I’ve found you, I’ll make sure not to touch you.” Even if the snail is vicious, we could appeal to its self-interest: “Hey snail, I don’t know what you have against me, but how about I set you up with a steady supply of food? If you kill me, the deal is off and you will have to work for your food again, so it’s in your best interest not to touch me.” Wouldn’t the snail say, “Sure! Works for me!”?

Zero-Sum Thinking Throws Some of Us Under the Bus

A pervasive metaphor in our culture is that our resources are like a pie, and so we need to defend our piece against all the other people out there who would take it from us, as though our country were a Thanksgiving dinner beset by hordes of hungry cousins.

Our family used to have our own recurring zero-sum conflict over pie (well, pizza pie). Every Sunday, we would go out for pizza, and every single time, my kids (Casey and Noah) and I would each order our own pie, and my husband would say he wasn’t hungry and would just order soup. The pizzas would arrive, and they would look and smell delectable, which would whet my husband’s appetite. And so he would ask for a piece from each of our pizzas. (He prefers variety to getting a single kind of pizza anyway.) Casey and I would fork over a slice, but Noah, a growing teenager who has also inherited my ginormous appetite, would want his entire pizza. So every week there would be an argument over whether Noah should give up one of his slices.1

Zero-sum thinking is reinforced by those movies, TV shows, and books—for example thrillers and superhero movies—in which the hero must kill the villain, lest he be killed instead. Many of our political conflicts are caused by our belief that for someone to win, someone else has to lose. Zero-sum thinking prevents us from adequately funding a social safety net, from providing a good education for all our kids, from implementing universal healthcare, from taking action to fight climate change, from building affordable housing, and from developing sensible policies on immigration. It’s one reason we can’t have nice things.

However, most of the time, with a bit of creative thinking, we can find a solution to such conflicts so that everyone is better off. We just need to be willing to reject zero-sum thinking.

As discussed above, we can have a rational discussion with that deadly snail—and potential foes in the real world. We can choose a restaurant that offers not only whole pies, but also pizza by the slice. We can admit to ourselves that an educated, healthy, housed population might cost us a bit up front in higher taxes for the one percent but will pay off in the long run because we won’t have to spend as much on law enforcement, prisons, emergency-room visits, and climate-change catastrophes. Even better, we will benefit from the talents and skills of all the people who are able to contribute because we gave them a good start.

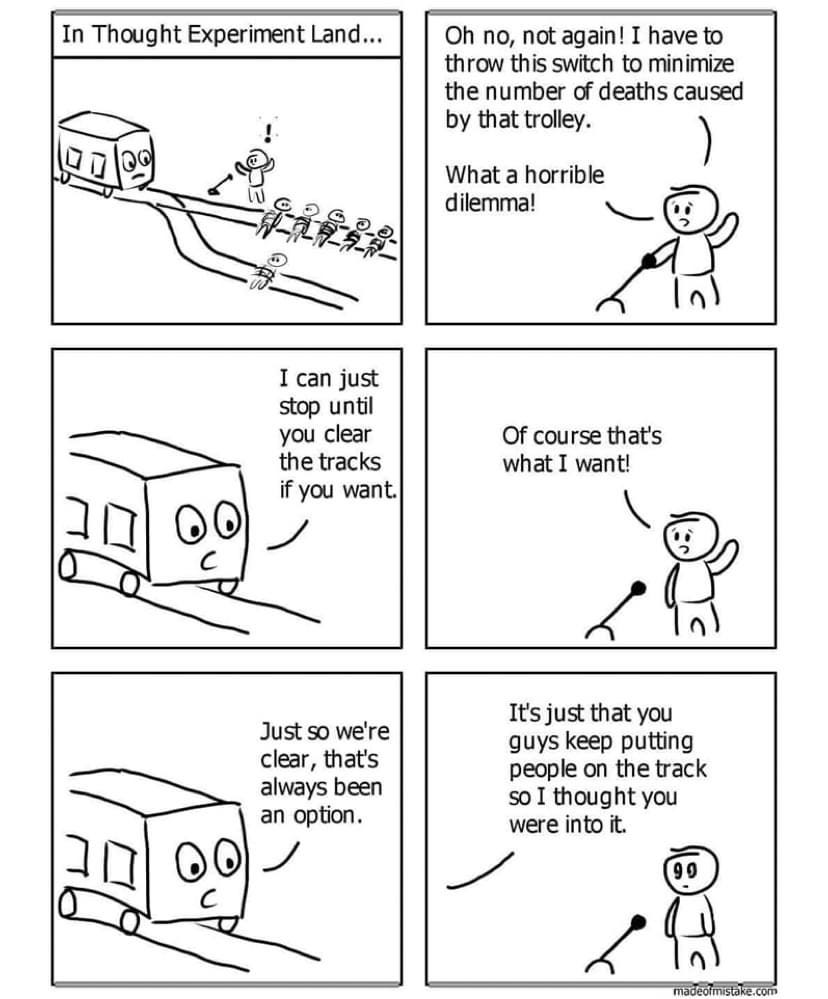

I reject that manipulative trolley problem, which constructs a situation where no matter what we do, someone will die. We can refuse to throw some people under the bus (or trolley) to save others. I prefer the attitude in this cartoon:

So while it is tempting to think that life is like a pie, and that other people are trying to grab our share, leaving less for us, in fact almost all situations are actually like a potluck dinner: We all have something to bring to the table (literally and figuratively), and the more we contribute, the more everyone receives in return. I’ll close this section with two recommendations:

In this podcast episode, negotiator Misha Glouberman shows us how to have meaningful conversations with people in which everyone comes away feeling like a winner. Glouberman even manages to reach a satisfactory arrangement with a local bar whose noisy outdoor beer garden has been tormenting the neighborhood. What is this wizardry? Listen and find out!

In this Experimental History post, the psychologist Adam Mastroianni shares tips from a course on negotiation that he teaches at Columbia Business School. You’ll learn how to get a good price—and a satisfied customer—the next time you need to sell a couch. Plus, Mastroianni’s witty and self-deprecating asides will make you laugh.

Difference Does Not Imply Hierarchy

When I was in my early twenties, I had a friend who was a cat person, whereas I—as attentive readers have no doubt sussed out—am a dog person. My friend and I fought like, well, like cats and dogs, about whether cats or dogs were better, and I am embarrassed to admit that most of those arguments were started by me.

Obviously this was a dumb thing to argue about, but it is also typical of a false belief that contributes to zero-sum thinking: That if people (or pets) are different, then there must be a hierarchy, with one group being superior to the other. It then logically follows from this imposed hierarchy that there must be winners and losers. But this way of thinking actually makes us all losers, because it causes us to undervalue and waste people’s talents, talents that may well turn out to be quite useful if we let go of the idea that they are lesser.

To illustrate this point, let’s look at a spurious hierarchy that makes everyone worse off:2 our assumptions about men, women, and STEM. Many people who hold power in our society, most notoriously the former president of Harvard and Secretary of the Treasury Lawrence Summers, have argued that men are by nature better than women at math and science, and that this is the main reason that more men than women work in STEM fields.3 People who think this way put men and women into a hierarchy of talent, where men are the winners (of well-paying, high-status jobs) and women are the losers, and there is nothing we can do about it.4 Summers wasn’t entirely wrong: Men are vastly more likely than women to be chess grandmasters, professors of pure mathematics at top universities, and Lego Master Builders, and this predominance really does seem to be caused by the extraordinary abilities in abstract and spatial reasoning possessed by a handful of men at the extreme end of the bell curve.

These rarefied fields aside though, most STEM jobs require not only talent for math and science (talent, it ought to go without saying, that is not exclusive to men), but also such personal qualities as being cooperative and conscientious. Our image of a lone, eccentric, scientific genius scribbling away in a garret is ahistoric; these days nearly all work in STEM is done by teams of workers. Yes, STEM needs tech geniuses,5 but to be successful, companies and universities need workers who combine technical ability with curiosity, a willingness to learn from others, a meticulous eye for errors, and an ability to be an effective member of a team—qualities that men and women share.

We Are Pieces of the Puzzle

In fact, sometimes when we are weak in one area, we become particularly strong in another. To see what I mean, take a look at the picture below. Can you tell what it is supposed to be?

Are you stumped? Here6 is the answer. Because I am horribly nearsighted (an undeniable weakness), I could identify the picture at a mere glance (a strength; stereograms are also very easy for me). My inability to see at a distance causes me to see more clearly in other ways. Yes, this is a metaphor too, for all those cases where our deficits are hidden strengths. A few examples:

Temple Grandin’s visual thinking made traditional school difficult for her but now enables her to design humane slaughterhouses;

People with ADHD may have trouble with executive function but are able to hyperfocus on tasks that neurotypical people would find challenging;

People who have struggled with disabilities and illness often have more empathy for the struggles of others and can thus be more effective and compassionate teachers, therapists, and medical professionals;

People who don’t care what others think of them might not be so attuned to formal etiquette, but we have an easier time learning languages because we don’t get embarrassed when we make mistakes in front of other people (as someone who makes a lot of mistakes when speaking German, I endorse this theory!).

My favorite example of a weakness that is also a strength are those people who have no filter and just blurt out what they’re thinking. This can lead to social awkwardness, true, but in many cases the more hesitant types will appreciate their outspokenness. As my husband used to tell his math students on the first day of class,

This is the point at which most of your professors would say that there is no such thing as a stupid question. But you know, and I know, that that’s not true. The problem is, if you don’t ask your stupid question, you—and probably others—will only get more confused, and you’ll just have to ask a stupider question later.

In public as well as private life, we need those intrepid souls who will ask the tough (even stupid) questions, and who will give voice to what we were all thinking anyway.

Instead of seeing our differences as a hierarchy, we ought to think about them as complementary. To invoke yet another metaphor, most of life isn’t a contest with winners and losers but rather a puzzle we build together, each of us offering our individual pieces to complete the picture. Or, as Rick put it in our discussion of “Bartleby, the Scrivener” a couple of weeks ago,

Most people are not perfect at their jobs and have some deficiency that we wish they could fix. But if you have enough people working together, you can usually overlap their strengths and deficiencies to get overall good results. As a manager I would embrace this idea, and work to make the best of the people I had.

If we understand our differences as strengths, we will profit from everyone’s interests, talents, and perspectives. We can all be winners.

A Brief Word about Sports

At this point I can hear readers protesting, “This talk of win-win is all well and good, but what about sports? A game can have only one winner!” And I agree; with the exception of soccer and amateur hockey, there have to be winners and losers in sports. And yet I maintain that competition in sports is also a win-win. Playing and watching sports is fun precisely because of the challenge and the suspense over which side will win. Besides, even when we lose, playing against a stronger opponent can help us learn from our mistakes and improve.

Moreover, sports give us a low-stakes outlet for our natural tribalism and for our tendency to put groups into hierarchies. When we insist—in the face of all evidence sometimes—that our team is the best, and definitely superior to that hated other team (cough cough Dallas Cowboys), we bond with fellow fans without hurting anyone else. Even when our teams lose, we spectators are still winners. Or, at least, as a lifelong Vikings fan, I can attest that there is a paradoxical comfort in commiserating with friends over our team’s getting knocked out of the playoffs every. single. year. We always hope that they will turn things around one day. (It can happen! After 108 years, Cubs fans were finally vindicated in 2016.) Sports is the one arena where zero-sum thinking is a win-win for everyone.

How about you, readers? Have you been in situations that looked zero-sum at first but turned into a win-win? Or where people whose different talents made the whole group stronger? Do you have a weakness that is actually an advantage? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Potluck or pie? How about both? A win-win! Below is a recipe for a pie that you can take to a potluck—or a Thanksgiving dinner with hordes of hungry cousins. The pie is great on its own, or you can top it with lightly-sweetened whipped cream: Whip 1c heavy cream with 1T sugar and 1tsp vanilla until soft peaks form.

Maple Pecan Pie

For the crust:

Ingredients

1c flour

1/2c (112gms) unsalted butter, chilled and cut into 1cm cubes

1T sugar

1/4tsp salt

3T vodka from the freezer (you already had a bottle of vodka in your freezer, right?)

Method

Put all the ingredients except the vodka into the food processor. Then, with the processor running, slowly drizzle in the vodka. Continue processing until the dough comes together in a ball (this takes about thirty seconds).

Remove the dough, flatten it a bit into a thick disk, and chill for about half an hour.

Roll the dough out and place into a buttered pie pan, patching the cracks if necessary. Poke the crust with a fork a few times to allow steam to escape.

Weigh down the crust with pie weights (I just use three pyrex ramekins) and bake at 400F/200C for twenty minutes. Remove pie weights and bake another ten minutes or so, until the crust is slightly browned.

Remove crust and set on a rack to cool.

For the filling:

Ingredients

4 eggs at room temperature

1c brown sugar

1/2c pure maple syrup (don’t use the kind that is just corn syrup with maple flavoring)

1/2tsp salt

1/4c (56gms) unsalted butter, melted

1tsp vanilla

2c pecans, toasted and coarsely chopped

Method

Beat eggs and then add in all the rest of the ingredients except the pecans. Beat until the mixture is smooth.

Sprinkle the pecans into the prepared crust and then pour the egg mixture over.

Bake at 400F/200C for ten minutes and then reduce oven to 325F/160C and bake another thirty minutes or so, until the filling sets. WARNING: Depending on the size of your pie pan, the filling might expand and drip all over your oven. I recommend putting foil below the pie pan to catch the drips.

Cool to room temperature before serving. Top with whipped cream if desired.

One time Noah tried bargaining: “What will you give me for a slice?” My husband, who had paid for the pizza after all, replied, “The rest of the pizza.”

I chose this particular example because I find it especially misguided and frustrating, but readers no doubt have their own examples.

Summers later clarified that he believes other factors—such as the eighty-hour work weeks that are typical of many STEM jobs—also contribute to the paucity of women in these fields. I would argue, though, that eighty-hour work weeks are inhumane for men and women alike. Rather than shrugging and saying, “Oh well, women just can’t handle such long hours, so I guess they can’t work in STEM,” we ought to mandate sensible, manageable work weeks, which would benefit all workers.

It is fascinating to me that people who tout men’s superior mathematical ability never mention the overwhelming gender imbalance in the opposite direction in jobs that require linguistic ability. Women outnumber men two-to-one as translators and interpreters, and the genre of literature that is almost exclusively written by women (romance) is more than twice as profitable as all other genres of fiction. And yet wouldn’t it sound ridiculous to say that books by women make so much more money than books by men because women are intrinsically better than men at language?

I contend that Google was correct to fire James Damore, though. Tech genius or no, Damore demonstrated that he was unable to work collaboratively when he dismissed his female coworkers’ abilities and claimed that they were “prone to neuroticism.” You would be prone to neuroticism too if some whippersnapper publicly suggested that because you are a woman you aren’t good enough at coding to work at Google.

It’s Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring.

My personal favourite for something that should not be pie: grades at school. I don't like places where by decree, only something like the top 5% of students are allowed to get a grade of 1 or whatever the highest one is. If one year more children/students do great work than usual, they should all get recognition for it!

Lovely column, Mari. On the topic of the man-as-genuis trope, one could argue that Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos have done more damage to the U.S. with their solipsism and out-of-control financial aggressiveness than many another ordinary person, whether male or female, and yet their genius still gets referred to and credited. They may be geniuses, but they're also jerks of the highest order. That should matter, too.

An aside, Arthur grew up without pets, now loves dogs since we have had two dogs, but insists that cats are evil. He has taken the hierarchy to a whole new level!