Rationing Is Good, Actually

Thoughts on Healthcare, Part 2

Welcome to week 2 of the Happy Wanderer healthcare series!

Part 1 discussed the systems in Czechia and Switzerland.

Part 2, this week, argues that rationing is good, actually.

Part 3 will offer ideas to improve our system and will pose some questions for discussion in the comments.

How’s that for a provocative title? Am I seriously claiming that it’s good to ration healthcare? Why yes I am.

Incentives and Trust

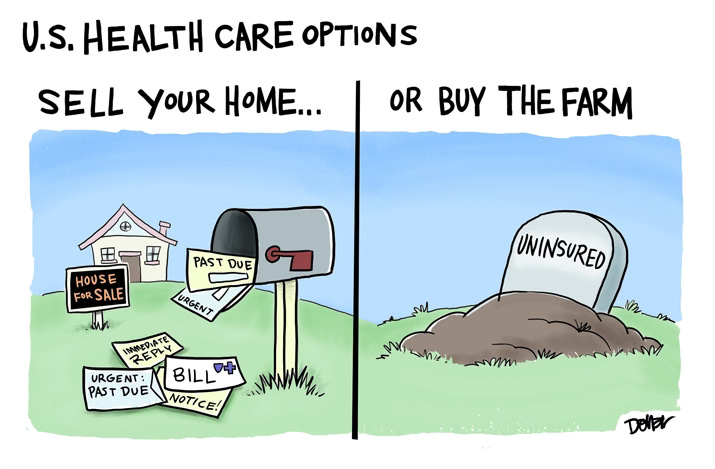

I am not talking about rationing in the US, where insurance companies deny necessary care to save money. As just one example, one in six people with diabetes in the US needs to ration their insulin because of the cost, and people have even died because they couldn’t afford their insulin. It is shameful that in one of the richest countries in the world, more than a quarter of the population forgoes medical care because they can’t afford it, and millions go bankrupt because of medical debt.

In the US healthcare system, most insurance companies are for-profit corporations, and an increasing number of medical practices and hospital systems are owned by private equity. In a for-profit system, it is reasonable for us to suspect that treatments are being denied not for our own good, but rather for the good of shareholders’ bottom line.

So we come by our suspicion of rationing honestly. But no country has infinite money, and so rationing is inevitable. The challenge is to ration based not on cost alone, but rather on whether treatments are proven to be effective and appropriate for the patient. Our current system has both too much and not enough rationing. True, people who can’t pay are denied healthcare they need. But people who can pay often receive healthcare they don’t need, enduring treatments that are not only expensive but also stressful, painful, and harmful.

Miracle Drug or Poison Pill?

When I was in my early twenties, I developed acne for the first time in my life. An acquaintance, who had a glowing complexion, mentioned that her doctor had put her on Accutane. I hied myself to my doctor and asked if I could get Accutane too. She told me that Accutane was expensive, and that the drug’s side-effects—which include a high risk of damage to one’s eyes and liver—were so serious that doctors only prescribed it for patients with disfiguring acne. Well ok then! No Accutane for me!

I trusted my doctor. I also knew that because she was a salaried employee of our university hospital, she didn’t have a personal financial stake in which drugs her patients took or didn’t take. While the cost of the drug may have been one factor in her recommendation, her main concern was my health, and so she was reluctant to overtreat my few pimples with a toxic drug. I’m grateful for her restraint, because my eyes and liver were protected, and the acne went away on its own.

The Curious Case of the Benevolent Insurance Companies

At least once in recent memory, insurance companies were a force for good (source). Since the 1950s, high-dose chemotherapy with bone-marrow transplant has been used as a treatment for leukemia. In the 1980s, women with advanced breast cancer began to demand that this therapy be available for breast cancer patients too. Insurance companies initially refused to fund the treatment, arguing that it was an experimental, unproven therapy. This decision caused enormous outrage; I remember op-eds characterizing the insurance companies as greedy and evil. Dozens of lawsuits forced the companies to pay for the treatment for thousands of women.

But it turned out that the insurance companies were correct: Research ultimately showed that this treatment was ineffective for advanced breast cancer. Worse, high-dose chemotherapy with bone-marrow transplant is an unimaginably debilitating and brutal process that caused crippling and even lethal side-effects in the women, including sepsis, kidney failure, and leukemia and lymphoma. More treatment, and more healthcare expenditures, are not always better.

Don’t Just Do Something—Stand There!

Well-insured people in the US are encouraged1 to undergo multiple medical tests at their regular checkups. Sometimes these tests identify abnormalities that don’t actually pose a danger to the patient. When this happens, patients may succumb to fear and opt for surgeries and medications that do more harm than good. Abnormalities—which we all have—don’t necessarily constitute a crisis requiring medical intervention.

But doesn’t early detection save lives? Well, yes and no. As Stanford oncologist Vinay Prasad observes, cancer screenings detect three kinds of tumors:

The first grow slowly and are unlikely to shed cells elsewhere. These are not going to kill you in your natural life.

The second are those that spread microscopic cells very early on. Even if you find them when small, they have seeded other organs. There is almost nothing you can do to avoid dying by this cancer.

The third type of tumor is the tumor that starts in the target organ, and was going to spread, and going to kill you, but because you find it and cut it out, you live much longer than you otherwise would. This is what we want to find!

Now consider that all three are indistinguishable under the microscope. All get the same treatment—surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

The problem is that finding tumors #1 and #2 is not good for you. You are subject to surgery, radiation and chemotherapy that you don’t need.

Let’s look at some examples of overtreatment of the first and second kinds of tumors. It is only natural that when confronted with a mammogram showing ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), many women are frightened and just want the thing out of their bodies. But “most DCIS lesions remain indolent” (i.e. will not develop into cancer; only about one tenth of one percent of DCIS tumors metastasize), and surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation likely carry higher risks than the DCIS itself. Similarly, men who undergo treatment for indolent prostate tumors find their lives blighted but not lengthened; they endure impotence and incontinence to treat slow-growing, non-lethal cancer. On the other side, terminal patients are sometimes pushed toward aggressive treatments2 that cause terrible suffering but that don’t appreciably extend their lives.

Routine surveillance testing may not be worth it for more mundane reasons too. These tests are unpleasant and time-consuming, and they expose patients to nosocomial infections. The burden of frequent doctors’ appointments is especially acute for seniors, who often have mobility issues and may not be able to safely drive to appointments. At some point the risk of a crash or a fall while getting to the doctor outweighs the benefit of the tests. A recent article argues that “medical care can become a wearying treadmill for older patients,” and that “Decreasing [low-value care] would save patients time and energy, prevent treatment cascades and reduce spending, including out-of-pocket charges.”3 In other words, rationing done right.

Rationing Done Right

I’ll close with a final example of healthcare rationing in Switzerland to demonstrate that healthcare systems can save money without compromising patient health. Switzerland offers free mammograms every other year to women aged 50–69 (age 74 in some cantons) who have no risk factors. By comparison, in the US the standard is annual mammograms beginning at age 40, with no upper age limit.

Even though women in Switzerland receive many fewer mammograms than in the US, Switzerland’s age-adjusted breast cancer mortality rate is lower than ours (12.4 per 100,000 women in Switzerland compared with 19.4 per 100,000 women in the US). How can this be? It is possible that annual mammograms from age 40 through old age are picking up not potentially fatal cancers (Dr. Prasad’s third type) but rather DCIS in younger women and indolent tumors in older women. The US mammogram standard could be subjecting women to harmful overtreatment without saving additional lives.

Similarly, colonoscopy is not standard in Switzerland. Instead, asymptomatic, low-risk people age 50 and older take the FIT test. The healthcare system is spared the cost of colonoscopies, and people are spared the extremely unpleasant prep, risk from anesthesia, and day of recovery. As with breast cancer, the age-adjusted colorectal cancer mortality rate in Switzerland, at 7.7 per 100,000 is lower than that of the US, where it’s 12.5 per 100,000.4

It can be difficult for Americans, accustomed as we are to insurance companies’ denials of necessary care, to accept that fewer tests and interventions could be a win-win—cheaper and healthier too. And yet Switzerland’s record shows that it is possible to ration healthcare in a way that benefits us all.

How about you, readers? Have you ever experienced healthcare rationing, either because of costs or because the treatment was inappropriate? What happened? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

To continue our theme from last week of Bee Gees’ covers, here is a wonderful version of “How Deep Is Your Love.” Infinity Song, like the Bee Gees, is a group of golden-voiced siblings singing in close harmony. Enjoy!

Many forces contribute to excessive testing and overtreatment. The “worried well” seek to quell their anxieties through frequent doctor appointments. People with a terminal diagnosis hope for a miracle. Doctors lack the time to persuasively convey the risks of overtreatment and the benefits of watchful waiting or palliative care. They also rightly fear malpractice suits. And for-profit healthcare systems have a financial incentive to perform tests and procedures for which they can bill patients.

Cancer patients purchase chemotherapy drugs directly from their oncologists, and not from independent pharmacies, and so it is legitimate to ask whether the profit motive is influencing oncologists’ recommendations to terminal patients.

Several comments to the article testified to the suffering and frustration caused by the healthcare treadmill. One woman described the pain and terror her 78-year-old mother, who has dementia, experienced during a mammogram. Other commenters pointed out that it is difficult and painful for frail people to get in and out of the car and to sit in uncomfortable waiting rooms for hours on end. One commenter, a “healthy 76 year old,” was told by her doctor that all her test results were terrific. And then he added, “I don’t see you very often. People your age should be coming in every 3–4 months.”

Two caveats: First, the statistics I found for age-adjusted mortality rates for breast and colorectal cancers in the US and Switzerland come from slightly different years. For breast cancer, the US figure is from 2019 and the Swiss is from 2022. For colorectal cancer, the US figure is from 2020 and the Swiss is from 2022. However, these years are close enough, and the differences in mortality rates are significant enough, that it is doubtful that one or two years on either side would make an appreciable difference.

The second caveat is that Switzerland is a richer country than the US and has much less obesity than we do. So we would expect a lower rate of cancer deaths in Switzerland for these reasons alone. Then again, smoking is also linked to breast and colorectal cancers, and the smoking rate in Switzerland is twice that of the US (24 percent of people in Switzerland smoke, compared with 11.6 percent in the US). So perhaps it’s a horse apiece.

I agree that in the U.S. there is a rapid escalation of over medicalization. Older people seem to expect they will have joint replacements, for example. At my annuals I am given prescriptions for all the tests. I usually skip them. I agree 100% with Barbara Ehrenreich's last book,

Natural Causes: An Epidemic of Wellness, the Certainty of Dying, and Killing Ourselves to Live Longer. (2018)

If you will be so kind, let me proselytize against statins for general use to lower cholesterol. Evidence is clear a statin will lower cholesterol; the part about statin-lowered cholesterol number preventing strokes and heart attacks is way less proven. And for anyone having joint and muscle pain issues, don't necessarily listen to physicians who guess neuropathy or arthritis as the cause (with more drugs prescribed). First, stop the statins for a few weeks. Then if the pain decreases or disappears, decide on your own which is preferable for your life: real pain and motion limitation from statins or the off-chance a lower cholesterol number prevents a stroke.