At my alma mater, first-year students begin their college career by reading Plato’s Apology, in which Socrates famously says,

Although I do not suppose that either of us knows anything really beautiful and good, I am better off than he is—for he knows nothing, and thinks he knows. I neither know nor think I know.

It was a perfect way to suggest to a bunch of know-it-all teens (in which category I definitely belonged) that in order to learn, we must admit that we have a lot to learn. I took this lesson to heart. Many years later, at a family dinner, my brother-in-law asked my opinion about an issue, and I responded, “Oh, I don’t know enough about that to have an opinion.” He started laughing and joked, “You’re supposed to say that the OTHER guy doesn’t know enough to have an opinion!”

We can be too eager to accuse others of ignorance, and too skeptical of experts. Like the gang from It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, we think, “science is a liar sometimes”:

But we can take this point further. Yes, sometimes we distrust experts because we’re too ignorant to understand what they do, but sometimes we distrust experts because the experts themselves don’t know everything,1 and unlike Socrates they don’t always know it. The most important trait for experts and regular people alike is not knowledge, but rather the Socratic ability to acknowledge that we still need to learn.

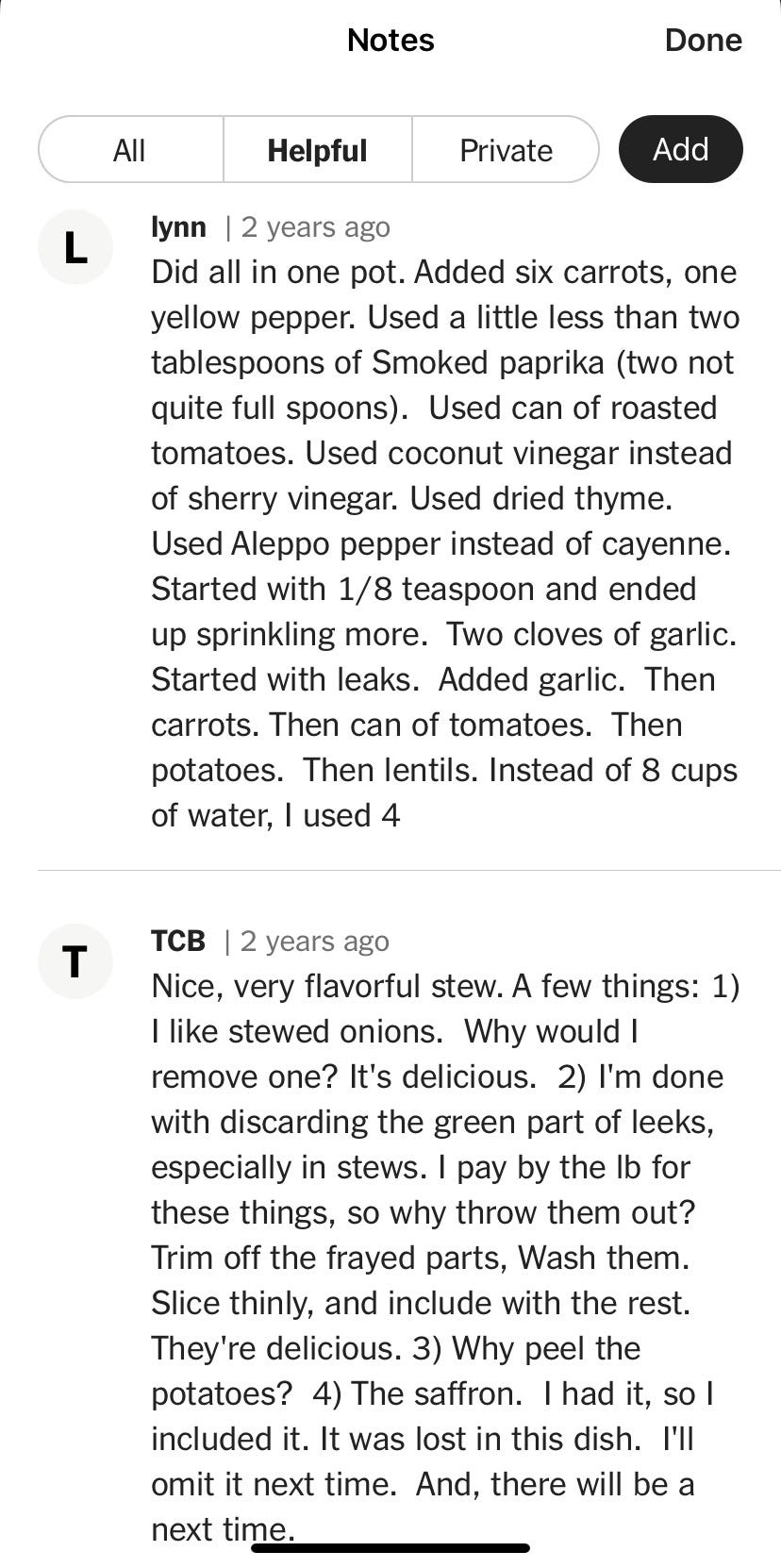

My compatriots on the left tend to think that distrust of experts is only a problem on the right, but this is not a left-right issue. We all do it. Here’s a whimsical example: While readers of the New York Times strongly favor trusting experts (especially during the pandemic), they can be skeptics too. How do I know? Because I subscribe to New York Times Cooking, whose readers are notorious for responding to any recipe—created, it bears mentioning, by culinary experts—by immediately questioning and changing everything about the recipe, often without even trying it as written first. Below is a screenshot from a typical comment thread to a recipe. There is no Times recipe so flawless, and no recipe-writer so expert, that hundreds of readers won’t pipe up with proposed improvements.

It’s ok to doubt a recipe, even one written by an expert, and to make substitutions that better accord with our own circumstances and preferences. That’s what cooks do. And it’s also ok to doubt experts when their recommendations don’t make sense for us. Cognitive biases make it difficult for all of us—experts included—to recognize what we don’t know. But the scientific method, curiosity, and humility can help us admit our ignorance and even change our minds.

1. Loss Aversion, the Profit Motive, and the Scientific Method

One cognitive bias that prevents us from admitting we don’t know everything is loss aversion. When we’re confronted with evidence that our way is wrong, too often we dig in our heels rather than cutting our losses and trying something new.

Which reminds me of a joke my husband heard when he lived in Russia: A Russian man is walking down the street, when he sees a Chukchik2 sawing off a branch he’s sitting on. “Stop!” yells the Russian. “You’ll fall!” The Chukchik keeps sawing. “I mean it! You need to stop!” persists the Russian. “Go away and leave me alone!” yells the Chukchik. The Russian tries one more time: “Seriously, if you keep sawing, you’ll fall and hurt yourself.” But the Chukchik ignores him. “Ok, have it your way,” grumbles the Russian and leaves. A minute later the Chukchik saws through the branch, falls to the ground, and, rubbing his twisted ankle, mutters to himself, “A Russian sorcerer is an evil sorcerer.”

The joke is funny because it’s true. We have all acted like the Chukchik at one time or another, doggedly insisting on doing things our own way when all evidence shows this is a mistake.

Loss aversion is made worse by the profit motive. For example, we now know that arthroscopic surgery does no better than placebo to relieve knee pain, and yet orthopedists, whose incomes depend on these procedures, continue to perform them. More recently, a ten-year, double-blind study of colonoscopy screening has shown that colonoscopy provides only minimal benefit over the much less invasive fecal immunochemical test (FIT) in detecting cancer and preventing deaths;3 the study suggests that for people with no family history of colon cancer, the risks of colonoscopy outweigh the benefits. It will be interesting to see whether gastroenterologists respond to this study by recommending that most patients can skip this lucrative procedure—and whether patients will accept the new recommendations—or whether loss aversion, fear, and the profit motive will trump the evidence.

We can be hopeful, though, because of the scientific method: When a study shows an assumption is false, scientists and doctors revise their conclusions. A famous example is peptic ulcers. Until the 1980s, everyone believed that ulcers were caused by stress, and patients were urged to keep calm and avoid spicy food, caffeine, alcohol, and other treats that make life worth living. And then one day the heroic researcher Neil Noakes drank down a flask containing H. pylori in a successful effort to demonstrate that ulcers were caused not by stress but by bacteria. Doctors changed their minds in response to the evidence, and ulcers are now treated with antibiotics—and patients can enjoy their coffee, wine, and spice pain-free. Instead of trusting experts, we’re better off trusting the scientific method, which helps experts know better.

2. WEIRD and Weird

A second obstacle to experts’ knowing that they don’t know everything is that they are WEIRD, and sometimes also weird. The acronym WEIRD stands for “western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic” and is often used to refer to foreign aid workers who are unaware of their own biases. An example of the mismatch between WEIRD aid workers and the people they were trying to help (which you can read about in this fascinating article) occurred in the 1970s in Lesotho. The aid workers observed that Basotho men let their land lie fallow and didn’t try to monetize their cattle. Instead, they traveled to South Africa to work in the mines. This didn’t make sense to the aid workers, who were used to an agricultural model of development. The aid workers tried to make the Basotho stay home and become farmers, to disastrous effect. The aid workers didn’t realize that the Basotho had never farmed before, that they owned cattle as a way of storing wealth and not because they were interested in ranching, and that they chose to work in the mines because they could make much more money there.

Another telling example comes from the field of psychology. The writer Andrew Solomon, who suffers from depression, once underwent an exorcism in rural Senegal, which, to his surprise, healed him. Five years later he interviewed survivors of the Rwandan genocide, who told him they found the approach of western therapists to be decidedly unhelpful, especially when compared with their own methods:

Their practice did not involve being outside in the sun . . . . There was no music or drumming to get your blood flowing again. . . . There was no sense that the entire community had taken the day off to try to lift you up and bring you back to joy. . . . Instead, they would take people one at a time into these dingy little rooms to sit around and talk about bad things that had happened to them.

Experts and would-be reformers can be weird in the colloquial sense too; they don’t always realize that not everyone shares their experiences and assumptions. Last month, the New York Times published an article with suggestions from the American Psychological Association for how to persuade men to go to therapy. The first suggestion was to tell men that therapy is “an opportunity to become strong.” While this approach will work with APA members and other people who are already convinced of the importance of therapy, it doesn’t seem all that compelling for anyone else. Wouldn’t a better approach be to make therapy more accessible and affordable? Or to have more male therapists? Or, I don’t know, to hold sessions on the golf course or during a fishing trip instead of in offices? Perhaps if the APA had thought to ask men what would work for them, they might have learned something.

It is particularly destructive when education experts don’t realize that they don’t understand the people they want to help. As Emily Hanford reports in her excellent and important podcast Sold a Story, for decades education experts have trained elementary school teachers in ineffective programs like Whole Language and Reading Recovery—and jettisoned phonics, the approach that actually works for most kids—in part because the experts love reading and find it easy; phonics seems boring and unnecessary to them. The experts observed that the best readers teach themselves to read spontaneously, and they decided that all children should learn to read that way. Unfortunately, the ability to learn to read by recognizing whole words and making guesses from context clues is extremely rare.4 The experts, and a fortiori a couple of generations of children, would have been better off if the experts had conducted their research instead on children who don’t have a special talent for reading, and had asked teachers and parents what strategies worked best for them.

As I have argued before, education experts are not typical: They come from the professional managerial class and are academically talented. Advocates of Common Core belong to that small, unusual group of people who would thrive under a regimen of frequent and rigorous testing. Their children would likely do fine in math lessons on an abstract “number sense,” language arts lessons on expository writing, and other developmentally inappropriate requirements of the Common Core curriculum for young children. These experts could afford to pay for private lessons, making it harder for them to see the downside in eliminating art, music, and PE, which many schools had to do to make room for testing in their schedules and budgets. Had Common Core advocates sought input from teachers and parents, it would have been obvious to them that their approach wouldn’t work (US PISA scores have not improved since its introduction) and that the loss of art, music, and PE would be devastating to children’s love of school.5

Readers may have noticed that I have repeated the words “ask” and “learn” throughout this section. This is because no matter how expert we may be, and how much we know, we never have complete information. If we want to know better, we need to be like Socrates, always aware that we have more to learn, always willing to ask, and humbly prepared to adapt.

How about you, readers? Which experts do you respect, and which do you suspect, and why? Was there a time you learned something important because you realized you didn’t know everything? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Check out the tweet below. See? Scientists need us regular people to keep them on their toes!

And here’s a special bonus tidbit: This recipe, for Thai red curry tofu, is by Yewande Komolafe, creator of some of my favorite recipes in New York Times Cooking. The curry is so easy and delicious that I make it without changing a thing.

(Well, ok, as you can tell from the photo above, I add bok choy, and meat eaters might want to substitute chicken for the tofu, but otherwise the recipe is fantastic exactly as written.) Enjoy!

Of course, another reason for this distrust is that we all remember multiple public-health panics fomented by experts and the media, panics that didn’t pan out: Alar poisons our kids! Cell phones cause brain tumors! Eggs give us heart attacks! Monkeypox is a threat to everyone, including children and monogamous heterosexuals! And, currently, Gas stoves will give our kids asthma!

Chukchiks are a typical butt of Russian jokes; Chukchick jokes are analogous to blonde jokes, except that Chukchick jokes are not pc. I still enjoy this joke, though, for how it mocks the stubborn illogic we are all guilty of sometimes.

The study, one of the largest randomized trials ever conducted, had 95,000 participants from four European countries. Throughout Europe it is standard practice to give patients the FIT and only offer a colonoscopy as a follow-up if the FIT detects genetic traces of colon cancer. For this study, researchers divided subjects randomly into two groups: The control, which was offered the FIT as usual, and the treatment group, which was offered colonoscopy. After ten years, 1.2 percent of the control group had contracted colon cancer, as compared with .98 percent of the treatment group.

One caveat is that among the treatment group, only 42 percent of the subjects underwent colonoscopies (we don’t know what percent of the control group chose to do the FIT). This sub-group did have a 50 percent reduction in colon cancer deaths as compared with the control group. However, it’s important to note that the risk of colon cancer death even in the control group was tiny—0.15 percent of people in the treatment group died of colon cancer, versus 0.30 percent in the control group. For comparison, all-cause mortality during the study period was 11.03 percent for the treatment group and 11.04 percent for the control group.

This is actually how I learned to read, at age three. But it makes no more sense to demand that all children learn to read the way I did than to teach, say, tap-dancing by plunking kids on a stage with Savion Glover and telling them, “Just watch him and do what he does.”

I highly recommend this interview with Temple Grandin, who advocates for reintroducing practical, hands-on classes like shop, cooking, art, machine repair, and sewing in schools. As she knows from her own experience, not all people learn verbally and mathematically, and neglecting visual and hands-on learners wastes the potential of too many people.

I think part of the problem is that people don't know what they're an expert in.

Imagine a CEO of a car company. Does know a lot about manufacturing cars? Maybe. But maybe he's just an expert in politicking is way to the top of an organization.

Or your example about education professors. Maybe they know a lot about education (sign point to "no"). But maybe they're an expert in saying the right things to get their papers cited by their peers

Socrates is the hero here, of course!