Strunk and White Are Not the Boss of Us

In Which I (Hopefully Convincingly) Advocate for Adverbs

Readers of the Happy Wanderer may have observed that I love adverbs and sprinkle them copiously throughout my prose. I do this not inadvertently or sloppily but in fact deliberately. While we are occasionally able to forage around in our brains and come up with the perfect verb, sometimes we come up empty. When we find ourselves stuck with a dull, vague verb, or one totally devoid of nuance, nothing beats an adverb for pepping up our prose.

So I feel faintly irritated by this advice from The Elements of Style, by William Strunk, Jr. and E. B. White:

Write with nouns and verbs, not with adjectives and adverbs. The adjective hasn’t been built that can pull a weak or inaccurate noun out of a tight place. This is not to disparage adjectives and adverbs; they are indispensable parts of speech. . . . In general, it is nouns and verbs, not their assistants, that give to good writing its toughness and color.

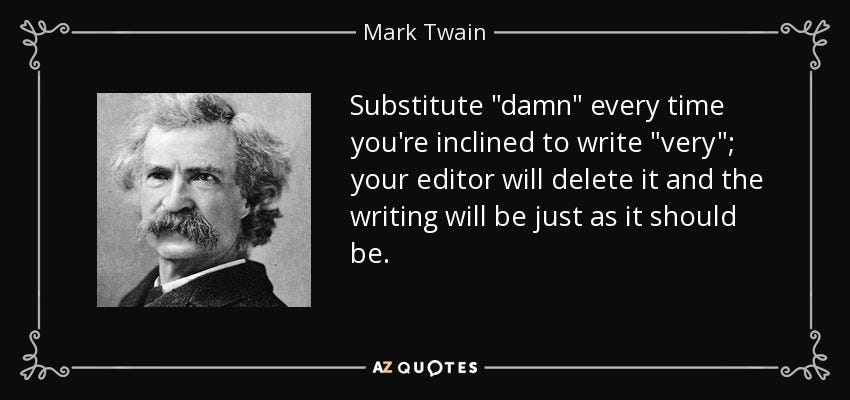

Before I launch into my defense of the humble adverb, I want to note one exception to my fondness for them—the word “very”; I follow Mark Twain’s advice:

Right. Now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, on to the defense.

The Case for Adverbs

I reject Strunk and White’s prescription utterly. What if we have other goals for our writing than to be “tough”? And, moreover, what if adverbs help rather than hinder our pursuit of “color”? I see three advantages to adverbs that help us write more effectively and enjoyably.

First, adverbs help us to convince a potentially hostile audience. Even if we want to be tough, for some of us toughness isn’t the most effective strategy for persuading people. Adverbs allow writers to sneak in our points subtly, discreetly, slyly, humorously, and entertainingly. This strategy of persuasion through indirection is useful for people who are in a subordinate position and thus can’t speak truth to power forcefully. Try being tough and blunt with your boss, or with someone who has higher status than you, and you risk that they will not listen to what you are saying but will instead channel their inner Lady Catherine de Bourgh and reply, “Upon my word, you give your opinion very decidedly for so young a person.” This problem is especially acute for women. Research has shown that when women are direct and assertive in their speech and writing at work, they are viewed as less likable or even aggressive, and they often face workplace penalties. So it can be rational to choose less straightforward, more conciliatory ways of speaking and writing, and in these situations, adverbs are our friend. Language peppered with adverbs is similar to the special “women’s language” in Japanese, which is more deferential and indirect than the men’s language, or the “uptalk” and apologetic language used by many American women and girls (and many young men too).

Second, far from clogging up our prose with needless words, adverbs allow us to express ourselves concisely and elegantly. For example, I recently texted a friend, “See you hopefully tomorrow and definitely Friday.” In my opinion this formulation is much less clunky than the version you get if you omit the adverbs: “I hope that I’ll see you tomorrow and I know that I’ll see you Friday.”1 And even though I proudly occupy the left end of the political spectrum, I still enjoy the following pithy and clever accusation from the master prose stylist Christopher Hitchens, that we on the left are “not even seriously wrong, but frivolously wrong.”2 Or take one of the most famous lines from Ernest Hemingway, which appears in The Sun Also Rises. Hemingway’s writing is normally held up as the epitome of tight, spare prose, and yet adverbs help him to express a truth in a quotable aphorism:

“How did you go bankrupt?” “Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

Third, adverbs allow writers to sneak in a bit of wit and color. Adverbs heighten and sharpen adjectives, making the descriptions more precise. Notice how Herman Melville’s adverbs shape our first impression of Bartleby the Scrivener: “A motionless young man . . . pallidly neat, pitiably respectable, incurably forlorn!” The adverbs “pallidly” and “pitiably” change our attitude toward the otherwise flattering adjectives “neat” and “respectable” and enhance the portrait of this forlorn young man. Adverbs improve our understanding of verbs too; they are stage directions that clarify how an action is performed. For example, Joan Acocella, writing in the New Yorker, describes the attitude of Napoleon’s soldiers when ordered to fight off the British: “They complied, dispiritedly, for two more years.” “Complied” is already precise and connotes lackluster obedience, but that “dispiritedly” really drives home the extent to which the soldiers are unwilling participants in this war. Or take how Jonathan Franzen, in his latest novel, Crossroads, strengthens the already negative verb “bragged” with a carefully-chosen adverb:

“I happen to have the original recording of Johnson singing ‘Cross Road Blues,’” he bragged, repellently.

A Few More Examples, Just for Fun

For the last several months I have been collecting examples of delightful adverbs. I’d like to share a few of them here, for our enjoyment and edification. (And, incidentally, I recommend all of these novels!)

From Crossroads:

[His fortune] had largely been squandered—poorly husbanded, inopportunely liquidated, charitably donated to garner status points, inadvisably divided among shiftless offspring.

From Our Country Friends, by Gary Shteyngart:

Even in class, Senderovsky would babble on, nervously, drunkenly—at times, she had to add a third adverb, charmingly—while the students pawed their phones beneath the giant conference table.

From A Confederacy of Dunces, by John Kennedy Toole:

Ignatius noticed hopelessly that she had added a dash of color by pinning a wilted poinsettia to the lapel of her topper. Her brown wedgies squeaked with discount price defiance, as she walked redly and pinkly along the broken brick sidewalk.

From Either/Or, by Elif Batuman:

Behind a dean’s strained expression, you could glimpse some hidden mechanism ceaselessly translating everything you said into an expression of unreasonableness or immaturity. But, for some reason, the laws of their universe didn’t allow them to openly oppose you. All they would do was smile fixedly . . . and, if you smiled fixedly back for long enough, they would eventually sign the petition.

From The Beginning of Spring, by Penelope Fitzgerald:

“I should be careful of the vodka if I were you, Uncle Charlie,” said Ben anxiously. “It doesn’t taste of anything but it’s quite strong.”

“Uncle Charlie needs something quite strong,” said Dolly.

“Well, I’ll take a little,” Charlie said amiably, “if your father thinks it’s good for me.”

“It’s not at all good for you,” said Frank. But the vodka, pliant, subtle, and fiery, eased the moment, as it had done for so many millions of others.

Fitzerald is famous for writing exceptionally spare prose, and for stringently sparing the adverbs in particular. But when she does employ them, they serve her goal of elegant concision. The juxtaposition of “anxiously” and “amiably” in this passage efficiently conveys a wealth of information about the two characters.

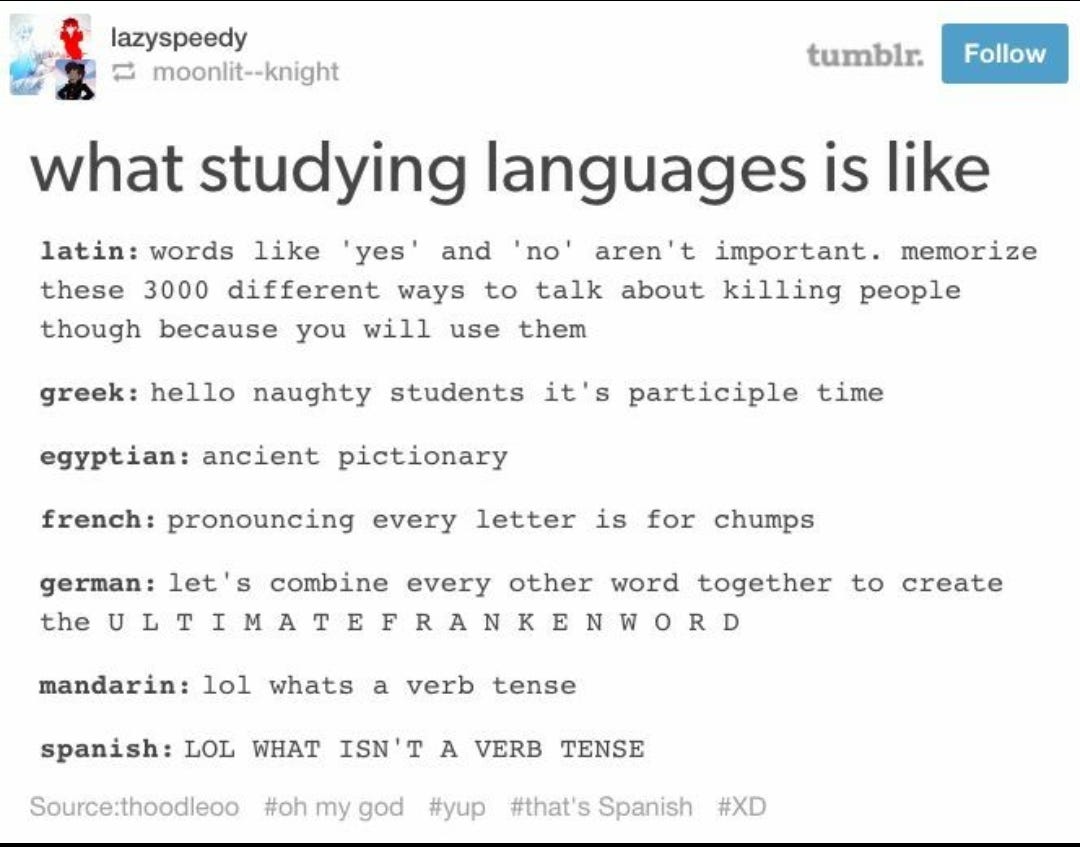

By contrast with the spare Fitzgerald, Henry James is famous for writing exceptionally baroque prose. In the spirit of that joke about learning languages, in which Mandarin asks, “What’s a verb tense?” and Spanish asks, “What ISN’T a verb tense?”3 I can imagine Fitzgerald cautiously pondering when she should use an adverb, while James, throwing caution to the winds, exclaims, “When SHOULDN’T you use an adverb?” Those of us who have been immersing ourselves in The Turn of the Screw have undoubtedly noticed an abundance of adverbs. In the following passage, the piled-up adverbs convey the Governess’s intrusive and chaotic emotions:

I preternaturally listened; I figured to myself what might portentously be; I wondered if his bed were also empty and he too were secretly at watch.

My final bit of evidence in the case for adverbs comes at the end of “Why I Write,” by one of the greatest practitioners of a tight, clean prose style, George Orwell. Note his strategic use of adverbs in the very sentences where he decries over-elaborate prose!

And yet it is also true that one can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one’s own personality. Good prose is like a window pane. . . . And looking back through my work, I see that it is invariably where I lacked a political purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally.

You may have guessed that I have a larger point, beyond defending my buddy the adverb, in writing this essay. Too often we get caught up in the false idea that there is only one way to do things—one way to write (use only nouns and verbs!), one way to get our babies to fall asleep (co-sleeping! No, Ferberizing!), one way to exercise (interval training! No, 10,000 steps!),4 one way to learn (Common Core and high-stakes tests for everyone!), one path for our lives (college then career!), even one way to make guacamole. But in truth, there are very few situations where there is only one way. In our wanderings through life, two roads may diverge in a yellow wood. We may lose our way and need to consult a map or a kind stranger. Or we take detours, we meander, we backtrack, we race forward headlong, we balance ourselves on precipices, we scramble up an apparently insurmountable obstacle on all fours and reach the top triumphant.

Rather than direct everyone along a single path, why not celebrate the marvelous variety of ways we go through our lives, express ourselves, solve problems, and experience the world?

How about you, readers? Do you prefer the tight, unadorned prose of nouns and verbs, or have I successfully made my case for the advantages of the adverb? And are there other situations in your experience where “the way we’re supposed to do it” doesn’t work for you, and you have developed a better approach? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

We ought not always to be so straightforward; playfulness is important in language as well as in life. To wit, this cartoon:

Yes, I am aware that some grammar purists think that “hopefully” should mean “full of hope” and nothing else. (For example, “My dog looked at me hopefully as I unwrapped the bacon.”) These grammarians object to using “hopefully” to mean “I hope,” but I don’t care. Colloquial English spoken here.

Of course, one reason I enjoy the accusation is the irony. Hitchens was speaking about the Iraq War, about which he was seriously wrong.

Personally, I like the advice from Freakonomics about the best kind of exercise: The best kind of exercise is “whichever one you will actually do.”

Successful advocacy: I concur! (from Shari/not Mari)

I love this. My publisher is anti-adverb, so I've had lots of them cut from my work. The guidance is that you can use them sparingly, but some editors reflexively cut them. And I want to say "No, but that was part of my small adverb budget...."