The Beast in the Jungle Is Not an Instruction Manual!

The Fourth-Annual Happy Wanderer Valentine's Day Post

To my husband’s relief, I don’t go in for fancy Valentine’s Day trappings like expensive jewelry or fine dining. (I do, however, appreciate the occasional bottle of single-malt Scotch he gives me.) I celebrate the day in my own eccentric way, by writing Substack posts.

For new readers, here are the previous Valentine’s Day posts:

Yeesh! Stop Pushing Polyamory on Us Already!

How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love Romance

How to Tell a True Love Story: The Case against (Some!) Rom-Coms

And while we’re up here in the italicized housekeeping section, an announcement: The Happy Wanderer will be off next week, but stay tuned for the end of February, when we’ll take a look at the most romantic scene ever to appear onscreen.

“No Passion Had Ever Touched Him”

Henry James’s 1903 novella The Beast in the Jungle1 tells the tragic story of John Marcher and May Bartram. They first meet when they are in their twenties, and Marcher reveals his deep, dark secret to May: He has “‘the sense of being kept for something rare and strange, possibly prodigious and terrible . . . that would perhaps overwhelm [him]’” (39). They meet again by chance ten years later, and Marcher acknowledges that he is still waiting for his special destiny

“to suddenly break out in my life; possibly destroying all further consciousness, possibly annihilating me; possibly, on the other hand, only altering everything, striking at the root of all my world and leaving me to the consequences” [39].

May asks, quite sensibly, whether the great fate could be falling in love? But no, Marcher is convinced that his destiny won’t be so mundane. Which is too bad, because it is obvious to anyone who is not a total narcissist that May is in love with Marcher.

May and Marcher agree to await Marcher’s fate together. Marcher briefly considers marrying May but decides against it, using his imagined destiny as his excuse. After many years, May contracts a fatal illness and, as she is dying, she offers herself to Marcher: “She had something more to give him; her wasted face delicately shone with it.” But, alas, Marcher remains oblivious, and May dies shortly after this conversation.

For years after May’s death, Marcher has no idea of what has befallen him. And then one day he visits May’s grave and sees another man at a neighboring grave. The man is utterly ravaged by grief. Marcher realizes that he has never loved May, or anyone else, enough to feel such devastation at their death. “He had been the man of his time, the man, to whom nothing on earth was to have happened” (70). He could have escaped this terrible fate, if only he had loved May: “Then, then, he would have lived. She had lived—who could say now with what passion?—since she had loved him for himself; whereas he had never thought of her . . . but in the chill of his egotism and the light of her use” (69).

Marcher’s Fallacy

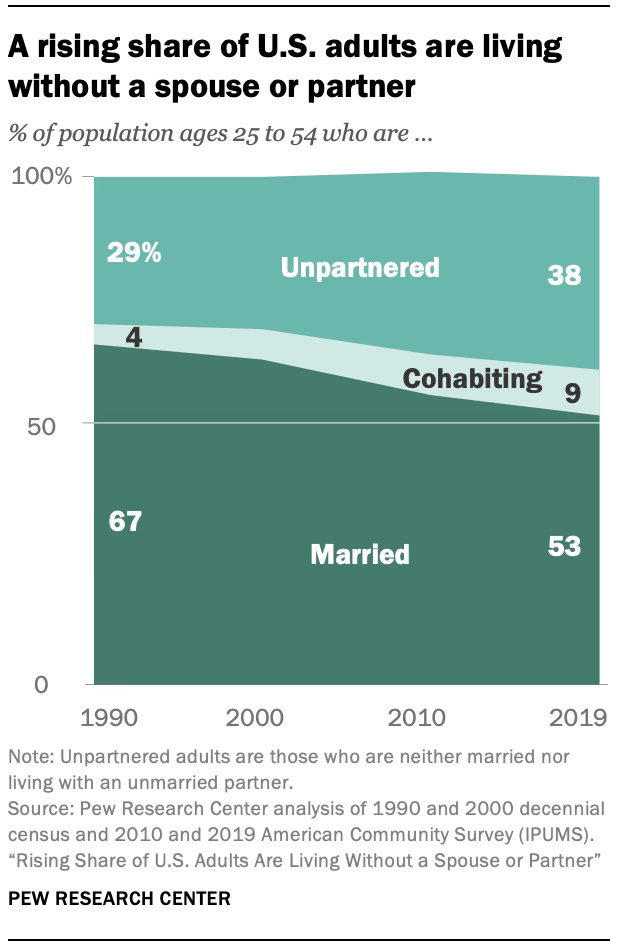

So what does all this have to do with Valentine’s Day? Well, a lot. We are currently suffering from a loneliness epidemic, one sign of which is that the percentage of US adults in long-term relationships is at an all-time low.

The marriage decline isn’t entirely bad, of course. In the past, economic pressure and the lack of birth control (for women), prejudice (against gay people), and social convention (for everyone) meant that traditional marriage was almost obligatory. In this system, people who were controlling, violent, unfaithful, or addicted, or who for other unimaginably horrifying reasons ought to have been unmarriageable, were nonetheless able to find spouses. Divorce saves many people from a lifetime of misery, and our current lower marriage rate partially reflects our freedom not to marry people who would mistreat us.

However, the marriage decline isn’t entirely good, either. We may talk a good game, but our work culture is not particularly conducive to healthy and happy relationships. The grueling hours US employers expect of workers make family life difficult. Meritocracy pushes the idea that nothing except career success matters, and that relationships are at best a distraction from what ought to be our life goals. Many of us can’t help but absorb this message, and the consequence is what I think of as Marcher’s Fallacy—the belief that a spectacular destiny awaits us, and so we must hold ourselves aloof from others while we pursue worldly success. This trend goes back at least to the nineties, when in my experience it was normal for couples to break up at graduation because they had job offers or graduate school in different states.

And, true, a small minority of us do indeed achieve greatness at work. A few more of us luck into a workplace that supports us when we’re sick or in trouble. But if we want love, happiness, and meaning in our lives, nothing beats friends and family. Our hustle culture tells us to be dedicated employees to the exclusion of everything that makes life worth living. We have the power to ignore this message, to choose to connect with other people, and to inspire and give love.

Nor Need We Obey “Will They Won’t They”

“Will-they-won’t-they” plots have existed as long as there have been stories. (Think of Penelope and the suitors in the Odyssey, medieval courtly romance, and Beatrice and Benedick in Much Ado about Nothing.) In old movies, external forces keep the lovers apart. Ilsa is already married to a hero of the Resistance.

Princess Ann has a duty to her people.

Dorothy can’t marry the Scarecrow2 because she has to go back to Kansas.

In movies from a generation ago, couples take forever to get together because the hero believes he is a lone wolf who is too cool to commit (for example in When Harry Met Sally and Judd Apatow’s entire body of work). But at least these movies know that the hero is deluded and not a role model.

The current version of “will they won’t they” is more pernicious. In these stories, one of the main characters, usually but not always the woman, forgoes a relationship for reasons of ambition or personal fulfillment—and the stories present this decision as smart and admirable. These plots tell us that we are correct to be selfish and to work on ourselves, and that until everything is perfect in our own lives, we can’t even consider being with another person.

A frustrating example of this message occurs in season 2 of Abbott Elementary. Janine and Gregory have had a slow-burn attraction for two years, but in the season finale, when Gregory finally declares himself, Janine refuses him because “maybe I am selfish.” She continues, “And if I need to be, I don’t want to wind up hurting you.” She sounds like Marcher when he decides not to marry May, allegedly for her own protection. But Gregory is not the type to be deterred or hurt if Janine needs to be selfish sometimes. Plus he’s handsome, smart, funny, great with kids, and absolutely besotted with Janine. Gregory would help, not hamper, Janine’s personal growth.3

The belief that relationships obstruct our freedom and dull our bright futures is everywhere in entertainment now. Here are a few examples just off the top of my head (but somehow in alphabetical order):

The Bear—Why did Carmy dump Claire? Lovely, bright, and ardent, she is exactly the inspiration he needs to lift himself out of his despair.

Gilmore Girls—Yes, Rory has a great opportunity to report on the Obama campaign, but that is no reason for her to refuse Logan’s marriage proposal (Team Logan!). Logan is super-rich! He could just buy a plane and visit Rory on the campaign trail anytime she has a spare moment.

La La Land—Don’t even get me started.

In fact the creators of movies and shows have different incentives than ours. “Will-they-won’t-they” plots exist not because constant uncertainty and high drama are normal and healthy, but because these plots keep viewers binge-watching to see what happens next.4 It’s fun to watch people yearn. But yearning ourselves? Not so much. These plots tell us that the perfect and life-changing person is out there somewhere, and the perfect time might arrive at some point in the future, but somehow it’s never right here, right now. But we, living our real lives, don’t have to listen.

“The Chance to Baffle [Our] Doom”

Names in James’s works are always symbolic. The name “Marcher” implies grim regimentation and mindless plodding. (He’s not named Wanderer, let alone a happy one, after all.) The month of March, like Marcher himself, is caught between chill winter and a breath of spring. “May,” by contrast, suggests reawakening to warmth and new life. The modal verb “may” conveys a sense of possibility and openness to change. Marcher believes that he is facing his fate courageously, but he is actually a coward. He fears taking a chance with another person.

In our own lives, when we refuse to connect with other people it is often because we’re afraid too—of the radical choice to put relationships ahead of worldly success, of the awkwardness and uncertainty of sharing our feelings honestly, and of the compromises that all relationships require. And yet we know in our hearts that the true doom is a lonely and selfish life. So let’s baffle our doom! Joy and meaning await us, if we only connect. This Valentine’s Day, let us dare to eat a peach! Let us love one another!

How about you, readers? Are you irked by “will-they-won’t-they” plots, or do you kind of like them? What do you think is the most romantic scene ever to appear onscreen? Any exciting Valentine’s Day plans? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Enough with the scruples, hesitation, and ambivalence! We’ll be happier if we emulate Benson Boone and tell the people we love how much we want and need them. If you haven’t seen the video of Boone’s performance of “Beautiful Things” at the Grammys yet, I promise you will NOT be disappointed! If you have seen it already, go ahead and watch it once (or twice, or ten times [sheepishly raises hand]) more.

Note: For copyright reasons, the video fades out halfway through the song. For the whole song, see the official video. Boone is only twenty-two and already has such an extraordinary voice (he’s been compared to Freddie Mercury) that he has to be heard to be believed. I think I’m going to watch the video again—how about you?

All quotations are from Henry James, The Beast in the Jungle and Other Stories, ed. Shane Weller (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 1993).

What?! Am I the only one who thinks Dorothy and the Scarecrow are secretly in love?

Janine and Gregory do become a couple at the end of season 3, finally.

There are similar competing incentives with dating apps. The goal for most people on dating apps is to find a partner and stop using the apps. But the goal of the apps is to keep customers on as long as possible, eternally scrolling and swiping, because that’s how the apps make their money. For more on the perverse incentives of dating apps, I highly recommend this article.

Every time I think I could like James’s work, I stumble on a sentence like this:

“to whom nothing on earth was to have happened”

W- w- ha- ha-!

What???

I'm not a good one to name onscreen scenes but my favorite romantic "scenes" come from Jane Austen's work. She was a master of narrative tension in interpersonal relationships, even considering the vast differences in social customs of her time. Even with her happy endings, she still kept the human foibles in view.

Great analysis and article- as usual!