This is the second of three best-books posts. For those just joining us, last week’s post covered literary fiction, and next week’s will discuss nonfiction.

What is “genre fiction” anyway? Most of us would agree that genre fiction comprises mysteries, thrillers, and spy novels; romance, young adult, and chick lit; science fiction, fantasy, and horror; and seafaring adventures and westerns. We could also add “book-club books” with character-driven plots offering multiple topics for discussion, for example works by Jodi Picoult, Jojo Moyes, Matt Haig, or Fredrik Backman.

But the line between literary and genre fiction is blurry; many works of literature feature suspenseful plots, while many works of genre fiction tackle important themes, experiment with language and form, and provoke thought. I think of genre fiction as following certain rules—the mystery must be solved, the couple must wind up together, and so on—but some of the best genre fiction breaks the rules and transcends genre.1 In other words, we read genre fiction for enjoyment rather than edification, but we may well become edified in spite of ourselves. And with that throat-clearing out of the way, let’s get to the list!

Down Cemetery Road, by Mick Herron (2003)

Herron is now justly famous for his excellent Slow Horses series (which made my list last year), but his first books—the Oxford series—are gritty, twisty, and enthralling too.

Down Cemetery Road, the first book of four,2 opens with a dinner party from hell. The hostess, Sarah Tucker, a whip-smart but underemployed housewife, is subjected to sneering remarks from her husband’s guest (who comes off as a repellent combination of Boris Johnson, Christopher Hitchens, and Jordan Peterson). Then suddenly there is an explosion down the street, which kills the parents of a young girl, Dinah. Sarah tries to visit Dinah in the hospital the next day and is rebuffed. The next thing Sarah knows, Dinah has disappeared, and no one will tell Sarah where she is. Sarah enlists the help of a private detective to track Dinah down. Is Sarah a reliable narrator, or is she addled by drugs or emotionally unwell and imagining the whole thing?

Not just a spy thriller, Herron’s book is filled with beautifully rendered observations about the interior lives of people whom others might dismiss as odd or unnatural:

She thought of the bonsai trees gardeners slaved over. … that there were trees, left to themselves, that might grow sixty feet tall, but instead had their roots punished to produce something small, cosseted, and ornamental. Something making up in charm what it had lost in dignity.

They sat watching the birds wheeling in front of them, as if in celebration of the gift of flight. Though actually, Sarah thought, birds didn’t do that: birds were just birds, no more capable of taking joy in their gifts than men were.

Exiles, by Jane Harper (2023)

Harper’s final book in her Aaron Falk trilogy3 takes Falk to a small town in South Australia’s wine country, where he will be the godfather at the baptism of his friend’s son. A close-knit group of friends grew up together there, and they are still coping with a tragedy that befell them a year before the story opens: Their friend Kim disappeared, leaving her six-week-old daughter abandoned in her stroller at a music festival. Five years before that, the husband of another of the friends was killed in a hit-and-run. The novel is told through frequent flashbacks, and these layers of time enhance the feelings of loss, which people who are mourning a loved one carry with them always. And yet this is also a love story, of landscape, of community, and of two people who take a leap of faith together. I am terrible about spoilers, and I don’t want to spoil this book, so suffice it to say that the book’s last few chapters convinced me that everyone ought to read it.

The Guide, by Peter Heller (2021)

What is evil? This book’s eponymous guide, Jack, learns from his teacher Marilynne Robinson that evil is “Impediment to Being.” What is good? I would argue that Jack, whose mottos are “Leave no one behind” and “What could be better than this, right here?” is our guide to how to live a life of virtue, generosity, and heroism. In this followup to Heller’s 2019 masterpiece, The River, Jack, brilliant but at loose ends and struggling with guilt and grief, takes a job as a fishing guide at a compound whose clients are billionaires (including a thinly-disguised Taylor Swift). The book begins at a slow burn, featuring Heller’s characteristically poetic descriptions of natural beauty. But even from the very first pages, when Jack wonders why he needs a code to open the compound’s locked gate from the inside, we know that something is terribly wrong here—and that Jack, courageous, resourceful, and good, will refuse to look the other way.

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, by Agatha Christie (1926)

This one may seem like an odd choice for a recommended reading list, given that pretty much everyone has already read this book or knows from the internet who the culprit is, including me (I read the book for the first time when I was twelve). But when the book showed up as a Kindle Daily Deal, I thought, “How can I afford not to?”4 and decided to reread it. It turns out that, if anything, the book is more fascinating when you know the secret, because you can observe Christie’s mastery in constructing her puzzle, a mastery that is astonishing in a first novel. No wonder she went on to become the best-selling author of all time.

An additional pleasure this time through, when we aren’t reading simply for the plot, are the wry asides and sly descriptions, often communicated through Christie’s judicious use of my favorite part of speech, the adverb. Here are a few particularly enjoyable examples:

Miss Gannett has all the characteristics of my sister Caroline, but she lacks that unerring aim in jumping to conclusions which lends a touch of greatness to Caroline’s manoeuvres.

She is all chains and teeth and bones. … She has small pale flinty blue eyes, and however gushing her words may be, those eyes of hers always remain coldly speculative. … She gave me a handful of assorted knuckles and rings to squeeze, and began talking volubly.

She doesn’t have those peculiar gurgling noises inside which so many parlourmaids seem to have when they wait at table. [Poor hungry parlor maids!]

The colonel’s story was one of interminable length, and of curiously little interest.

Pineapple Street, by Jenny Jackson (2023)

A bright, feisty young woman from a humble (well, she would say middle-class) background marries a handsome princeling from an old-money New York family. That’s the ending of most romances. But Pineapple Street opens in the decidedly not happily-ever-after. It’s early in the marriage of Sasha, a bohemian artist, and Cord, who works in his family’s business. Cord has made it clear that he will always put his family first. Cord’s sisters call Sasha the Gold Digger, and whenever Sasha hosts a family dinner, Cord’s mother, Tilda, expresses disapproval of Sasha’s “tablescapes” and brings her own catered dishes (causing the rest of the family to spurn Sasha’s offerings).

And yet in spite of these afflictions, this book is an absolutely delightful social satire with a light and generous touch. While I suspect Tilda (a brilliant comic creation) and the paterfamilias (who is absent on the golf course for most of the book) will never change, Sasha, Cord, and Cord’s sisters want to make the world a better place instead of just coasting along. (Tilda’s solution to this dilemma is a really fancy floral arrangement, incidentally.)

During her characters’ search for enlightenment, Jackson treats us to incisive observations and fun vignettes. I especially liked a character’s idea for an app that records drivers every time they honk their horn, and then, just as they’re trying to fall asleep, plays their total day’s honking back at them, loudly—although, as another character asks, Who would put that app on their own phone?

Romantic Comedy, by Curtis Sittenfeld (2023)

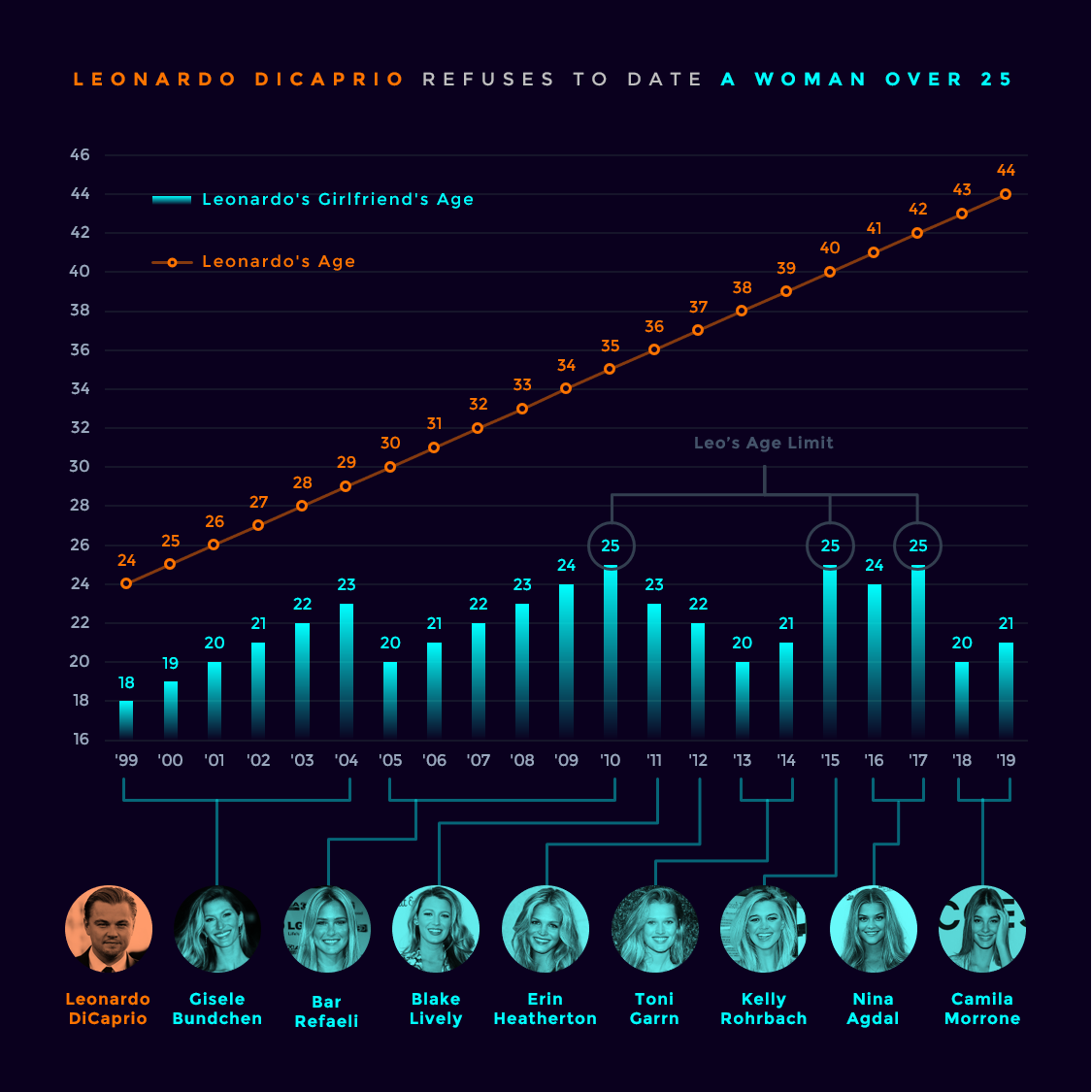

Many of us Plain Janes have frustratedly watched a lifetime’s worth of movies and shows where a schlubby guy gets a hot young girlfriend.

It happens in real life too:

We may have wondered why the reverse is never the case—why an average-looking woman never gets a gorgeous guy. Well, our wait is over. Sally, a writer for a nighttime live comedy show (think Saturday Night Live), is regular-looking but very funny and fun to be around. Guest host Noah, a pop star, turns out to be not just a pretty face but also smart, talented, and kind. Sally finds herself deeply in crush with Noah. But how could her feelings ever be reciprocated, given the disparities between their looks, money, and fame? Before anything can happen, Sally has to learn that

I had been one kind of person … a resigned and constrained person. Then I had been another kind of person for the last decade, a cynical and compartmentalized person. Was there any reason I couldn’t now become a third kind of person, made more confident by experience and braver by the current reminder of how fragile and tenuous all our lives had been all along?

This sparkling and enthralling story also features fascinating and well-researched details about what it’s like to produce a live sketch show, a deeply affecting epistolary section, and a grand romantic gesture that is simultaneously the most unusual and the most heartwarming you could ever imagine.

Small Mercies, by Dennis Lehane (2023)

Set during the Boston busing riots, Lehane’s historical thriller explores community—how it provides neighborly help and support but can also constrict people’s souls and mire them in anger, self-pity, and disappointment. Or, in the words of one character, “There were only two big sins in the house on Tuttle Street—feeling sorry for yourself and racism, which, when you think of it, are two sides of the same coin.” Community can also be a lie, as Lehane’s heroine, Mary Pat, discovers when a young Black man from the next neighborhood turns up dead, and her own teenage daughter turns up missing. And so Mary Pat sets out to find her daughter, and to figure out what is going on.

Mary Pat is a magnificent creation—full of contradictions, she is racist but has convinced herself that it’s for good reasons; she is simultaneously loving, suffering, and spoiling for a fight. She pulls no punches, literally. In one of the book’s best scenes, Mary Pat delivers a much-deserved beat-down (and proudly rejects its characterization as a fight because the other guy didn’t manage to land a single punch).

In the end, the book advocates for the importance of hope, because

you can’t take everything from someone. You have to leave them something. A crumb. A goldfish. Something to protect. Something to live for. Because if you don’t do that, what in God’s name do you have left to bargain with? … Maybe the opposite of hate is not love. It’s hope. Because hate takes years to build, but hope can come sliding around the corner when you’re not even looking.

Someone Else’s Shoes, by Jojo Moyes (2023)

I have enjoyed Moyes’s novels in the past, but yeesh can they be depressing. So when I was looking for some light summer reading, I was a bit wary when my mom recommended this novel to me. (I should never have doubted you, Mom!) I wrested an assurance from her that the book would not be depressing, and, because the story gets harrowing in a few places, I would now like to pass that reassurance along here. This novel confirms Oscar Wilde’s quip that “The good ended happily and the bad unhappily. That is what fiction means.” The fun and suspense are in how we get to that happy ending!

The story opens in a locker room, where downtrodden Sam accidentally picks up a gym bag belonging to Nisha, an uptight society wife. The bag contains a pair of red snakeskin Christian Louboutin stilettos—which turn out to be a life-changer for both women. The shoes are an amusingly unlikely MacGuffin throughout the novel. We also meet a sweet old dog named Kevin who is trying his best not to be incontinent, two teenage daughters who are snarky but good-hearted, and a dea ex machina in the form of a menopausal traffic cop. I predict that readers will also love a scheme involving a cat charity, a behind-the-scenes look at the lives of workers in a fancy hotel, and a dreamy Polish chef.

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, by Gabrielle Zevin (2022)

Who knew that the story of a trio of young videogame developers could be so powerful? The book’s title reinvents Macbeth’s despairing final soliloquy for the world of videogames, where characters die, come back, try again, fail again, fail better, and maybe one day even figure it all out. Sam and Sadie meet as children and reconnect as students at Harvard and MIT, where, together with Sam’s roommate Marx, they collaborate, create, fight, and reunite. Their story shows that there are multiple ways to express and share love; that creative work is the best antidote to trauma; and that play is how we learn, connect, and grow:

To allow yourself to play with another person is no small risk. It means allowing yourself to be open, to be exposed, to be hurt. It is the human equivalent of the dog rolling on its back—I know you won’t hurt me, even though you can. It is the dog putting its mouth around your hand and never biting down. To play requires trust and love.

A special pleasure in the book is the visually lush and philosophically provocative games the characters create. We imagine playing them ourselves, and sometimes, when we discover the game’s twist, we are forced to reconsider everything that went before. Kind of like life. My favorite scene in the book, of a bird soaring over a field of strawberries, moved me to tears. Trust me on this one.

Wrong Place Wrong Time, by Gillian McAllister (2022)

It’s after midnight, and Jen, a happily-married lawyer and mom, is looking out her front window to make sure her son, Todd, gets home by curfew. As Todd walks up the street, a stranger approaches. To Jen’s horror, Todd takes out a knife and stabs the man to death. The police come and take Todd away to jail. Jen wakes up the next morning in despair—and then she hears, in the next room … Todd. How can that be? Jen discovers that she has gone back in time, to the previous day. For the remainder of the book, she will regress further back in time, picking up clues she needs so that she can prevent the murder from happening. (I am amazed that no one has thought up this brilliant idea for a mystery before!)

The novel is a pleasure not just for its twisty plot, but also for its exploration of love, truth, and what it means to be a good mother. Jen thinks back to the exhausting days at home with a new baby, “Feeding him too much so he slept more, upending the bottle while watching daytime television, bored, no eye contact. That time she shouted in frustration when he wouldn’t nap.” Like all of us, she wasn’t perfect. But did her mothering cause Todd to become a murderer? Or was the problem secrets, lies, and “the horrible significance of events you had no idea were playing out around you”? I suspect that you will devour this book in a single day, as I did!

How about you, readers? What were the best books of genre fiction you read this year? Please share your thoughts (and recommendations) in the comments!

The Tidbit

Speaking of enjoyment and edification, one of my favorite bands is OK Go. Performance artists as well as musicians, the band makes wonderfully creative videos that are full of extraordinary stunts. In the video below, they stop time, literally, to remind us to savor every moment and to embrace love. The lyrics are a poignant echo of Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress”:

So while the mile reclaims our footprints

And while our bones keep looking back

The overgrowth is swallowing the path

Therefore the grace of God, go we

Therefore the grace of time and chance

And entropys cruel hands

So open your arms to me

This will be the one moment that matters

We all have our own examples of writers who (at least sometimes) cross the line between genre and literary fiction. For me such writers include Kate Atkinson, Tana French, Stephen King, Ruth Rendell, and Kim Stanley Robinson, among many others. I hope readers will share your favorite literary genre-fiction writers in the comments!

I just finished reading Herron’s Reconstruction (2008), which is a standalone spy novel but is also set in Oxford and grouped with his Oxford series. Highly recommended! Heck, I might as well recommend all of Mick Herron’s books and be done with it.

I recommend the whole trilogy, but you don’t need to have read the previous two books to enjoy this one.

This is a reference to a family joke. Many years ago, when my husband and I were newlyweds, he saw an ad for a law firm that would handle divorces for $65. He showed me the ad and said, “How can we afford not to?” We are well-suited to each other, because I (eventually) thought this was pretty funny!

Thanks for these recommendations, Mari! I now know to check out Mick Herron's Oxford series (having plowed through all his Slough House books). And, SMALL MERCIES, by Dennis Lehane--a masterpiece. Like you, I can't recommend it strongly enough, though not for the mystery aspect, which is good, but to get an understanding of the racial issues plaguing the U.S. and why they are so intractable, viewed through the lens of forced busing in Boston.