The Final Challenge

How to Keep an Open Mind

This is the third part of a three-part series on how we can work together to defeat glitches in our thinking. Part 1, “Think Better,” is here, and part 2, “Why Pay Twice?” is here.

Two weeks ago, we discussed strategies we can use in our own lives to avoid motivated reasoning. Last week, we looked at ways we can help each other to avoid the sunk cost fallacy. In both of these posts, the issues were somewhat contentious but not particularly left- or right-coded—whether alcohol is dangerous, whether the Power Pose is effective, and how to train medical residents, for example. I did this on purpose, because in our polarized times it is easier to keep an open mind and resist motivated reasoning and the sunk cost fallacy when the topics are apolitical.

When we keep an open mind, we often find ourselves thinking, “Huh. This issue is more complicated than I had thought at first. I think I need to learn more before I form an opinion.”1 This week, I’m inviting us to practice keeping an open mind about a couple of political issues, even though the first may be objectionable to readers on the right, and the second to readers on the left.

Everybody ready? Let’s psych ourselves up with a song!

Admit it: You secretly like this song, right? (Or is it just me? Never mind.)

This Can Work in the US!

Motivated reasoning and the sunk cost fallacy likely play a role in people’s objections to the two positions discussed here. Amusingly, people on both the right and left dismiss these ideas out of hand with the same knee-jerk rejoinder: “This could never work in the US!” When I ask why not, a common response is that the US is “too large and diverse.” And yet the first policy works well in the rest of the developed world (which, it bears mentioning, is also large and diverse), and the second was the norm worldwide, including in the US, until 2020.

When we encounter an idea with which we disagree (including, perhaps, right now), the following questions can help us keep an open mind:

Am I leaping to skepticism without hearing out the arguments for the other side first? Is it possible that I have an ulterior motive for thinking a certain way on this issue (motivated reasoning)?

Am I dismissing the arguments because of the kind of person who typically makes them? Is it possible that I hold a certain position on this issue not on the merits but because of my identity (sunk costs)?

Is there an aspect to this issue I haven’t considered before? Do I need more information before I make up my mind?

The US Should Provide Universal Healthcare

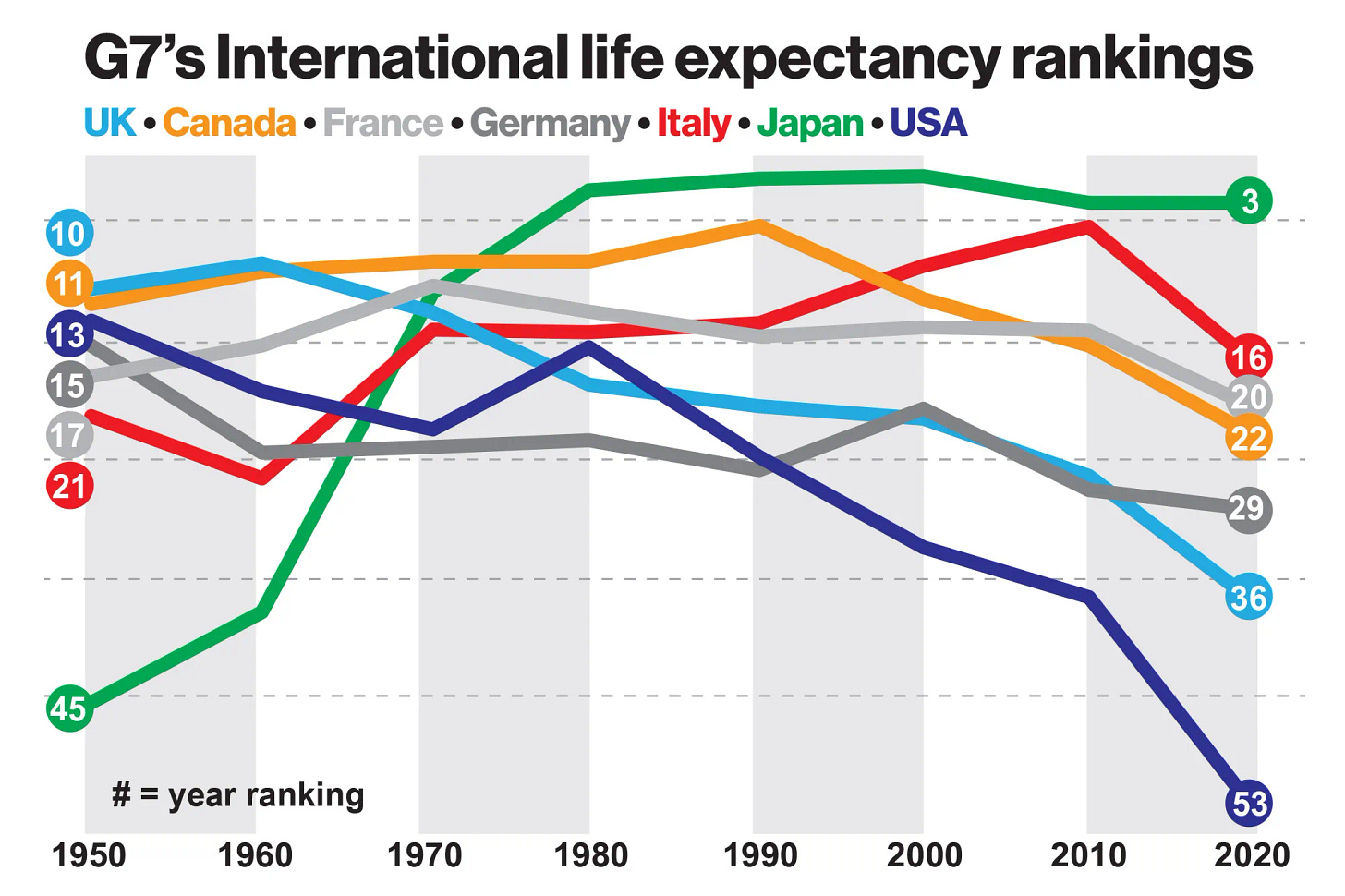

Some arguments you can make with a couple of images. The chart below compares life expectancy in the US with that in the other G7 nations:

It’s even worse than this chart lets on. As Statista reports, in 2022 US life expectancy ranked thirty-sixth in the world, behind much poorer countries (for example Chile, Costa Rica, Croatia, and Czechia—and that’s just the C countries!).

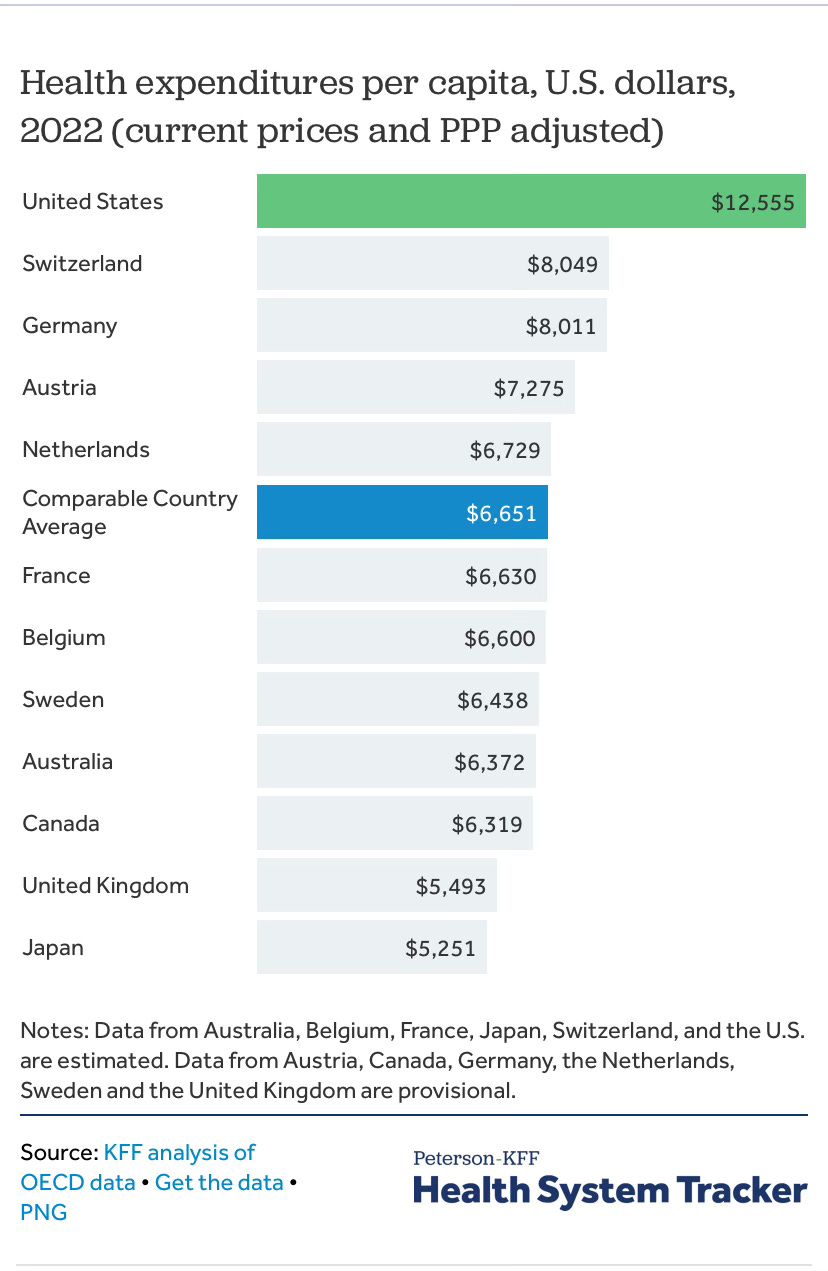

Now check out this chart:

We are spending more money to get worse results. In any other circumstance, reasonable people would find this situation intolerable and would clamor for change. Motivated reasoning bears part of the blame for our being stuck with such a kludgy, cobbled-together, inadequate system for providing healthcare coverage to Americans. People in power have a financial incentive to keep things the way they are, perhaps because they have invested in insurance companies, private hospital corporations, or Big Pharma, or maybe just because they are one-percenters who don’t want higher taxes.

In addition, literal sunk costs influence one group objecting to universal healthcare, the American Medical Association (AMA). While many individual doctors support universal healthcare, the AMA officially opposes it. When Obamacare was being debated, the organization published a statement against both single-payer and a public option, because, in their reasoning, “The introduction of a new public plan threatens to restrict patient choice by driving out private insurers.”2 In the years since, the AMA has somewhat moderated its stance, but it still opposes single-payer and a public option, and it suggests only hesitant, incremental steps toward covering low-income people, for example by “incentiviz[ing] tax credit eligible individuals to get covered” and “pursuing auto-enrollment for those individuals who qualify for zero-premium marketplace coverage.”

We can sympathize with doctors who oppose universal healthcare. They have invested enormous sums in their educations and in setting up their practices, and they understandably want to recoup these costs. We currently help them earn back this money through our confusing and unaffordable healthcare system. It would be much more efficient and beneficial to offer Americans a public option and to help primary-care doctors fund their educations through scholarships or student-loan forgiveness.

The US Should Not Impose Lockdowns in the Next Pandemic

Back in the summer of 2020, I changed my mind on lockdowns. At the start of the Covid pandemic I was firmly Team Lockdown, in part because I was repelled by anti-lockdown protestors in Michigan who blocked access to a hospital and invaded the state capitol brandishing guns. But my stance was also tribal—my side of the political aisle was all-in on lockdowns and scornful of protestors who wanted to, say, get haircuts, and for a few weeks I was right there with them.

Then I noticed that after Switzerland lifted its six-week lockdown, nothing bad happened. Quite the contrary, after Switzerland ended its Covid restrictions and reopened schools and businesses, cases plummeted, and deaths remained comparatively low for the duration of the pandemic. (I wrote this post about the Swiss approach.)

Before the next pandemic hits—and make no mistake, there will be another one at some point—we ought to figure out how to balance protecting our physical health with preserving our psychological well-being, children’s educations, social cohesion, and economic prosperity. To help us choose the best course of action, we can consult Our World in Data, which has published an “Estimated cumulative total of average excess deaths3 per day per 100,000 people from the start of the pandemic through January 27, 2024.” These data show that strict lockdowns were not associated with fewer excess deaths.

In the US the average daily number of excess deaths per 100,000 people was 405.81. In Switzerland, the number was 286.07. Switzerland’s excess death rate was also lower than all but one of the nearby countries, which had much stricter and longer lockdowns than Switzerland did:

Austria: 351.85

Czechia: 460.18

France: 235.84

Germany: 342.8

Italy: 507.57

We can also learn from Sweden, which never had a lockdown. Its excess death rate, 226.03, was comparable to Norway’s (201.21), higher than Denmark’s (150.75), and much lower than Finland’s (338.44).

Not only were lockdowns apparently ineffective, but they inflicted terrible costs, in the form of learning loss, closed businesses, more murders, and increased drug use and overdoses. Adding to these documented costs were all the intangible losses because of lockdowns—families unable to visit dying loved ones or attend their funerals, young children denied the opportunities for social learning they normally get in elementary school, and teenagers and young adults forced into isolation instead of developing relationships with peers. Worst of all, our already threadbare social fabric was shredded, too many people lost respect for the legitimate authority of scientific experts, and too many people became addicted to alcohol, drugs, and screens.

In all other recent pandemics (including H1N1 in 1977 and 2009 and SARS in 2002–4), health authorities did not impose lockdowns but instead offered vaccinations,4 protected the most vulnerable, and encouraged people to stay home when sick. During Covid, Switzerland and Sweden followed this tried-and-true model, and the evidence shows that their restrained approach protected their citizens not only medically, but also emotionally, educationally, and economically.

Why have people on my side of the political aisle been so committed to lockdowns? One possible reason is identity-based sunk costs: When Trump claimed that Covid was no big deal and would be over in a couple of weeks, most of us saw that he was wrong and quite sensibly disagreed with him—but then some of us went on to reject all ideas espoused by those on the right, even when they were supported by evidence.5 And of course millions of Americans have had terrible personal experiences with Covid. Fear is a form of motivated reasoning that can make it especially difficult to think objectively about the best way to respond to a crisis.

Justified True Beliefs

When our kids were in high school, they took a class called Theory of Knowledge, which taught them to evaluate claims and form justified true beliefs—beliefs supported by “adequate evidence. . . . [c]oherence with previous data and [c]larity with regard to language and logic.”6 I think it is a good practice for all of us to examine our beliefs periodically. Which are justified and true? Which do we hold for biased or tribal reasons? And how can we ensure that the majority of our beliefs are justified and true?

So now it’s your turn, readers: Challenge us! Do you have a justified true belief, on any topic, that you’d like to share? Make your case in the comments. We may discover that we need to learn more about your issue, and we might even change our minds!

How about you, readers? What did it feel like to try this exercise? Have you changed your mind about these issues, either now or in the past? Have you ever encountered an issue that turned out to be more complicated than you first thought, prompting you to learn more about it? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Whew! We deserve a treat, don’t you think? The recipe below, which I have waggishly dubbed Hot Potato, is my version of Bombay Aloo, or Indian-style potatoes. This dish makes a great side for Indian meals and is a peppy alternative to fries on burger night. You can also chill this dish and serve it instead of potato salad at a cookout.

Hot Potato

Ingredients

About 5 large potatoes or 8 small ones—I use celtiane potatoes because potatoes that are meant for mashing (for example russet) are too mealy for this dish

1T salt

1/4c vegetable oil

1–2T black mustard seeds

1 large or 2 small peperoncini, seeds and veins removed and discarded

a big-toe-sized knob of ginger root, or more, to taste (I use a LOT of ginger—i.e. the size of Shaquille O’Neal’s big toe)

1T each garam masala and turmeric (or more, to taste, but definitely don’t stint on the spices)

1/4tsp cayenne pepper, or more, to taste

1tsp salt

juice from 1 lemon

Method

Cut the unpeeled potatoes into chunks that are about the size of a superball. Dump them into a kettle with the salt and cover with water to about two inches above the potatoes. Bring to a boil and cook until the potatoes are not quite fully done—this takes about ten minutes at a rolling boil. (When you test the potatoes with a fork, they should have some give but not be totally soft.) Drain the potatoes in a colander.

While the potatoes are cooking, finely mince the peperoncini. Peel the ginger and, with a zester, finely grate it over the peperoncini bits, being sure not to lose any ginger juice.

Heat the oil in a large skillet over medium-high heat until it shimmers, and then toss in the mustard seeds. Cook, swirling the seeds around in the pan, until you can smell them. Then scrape the peperoncini bits and ginger sludge into the pan. (Warning: This stage is spritzy!) Cook briefly, tossing, and then add the salt and dry spices. Mix thoroughly.

Add in the potatoes, toss to coat, and cook until everything is heated through and the dish begins to sizzle.

Turn off the heat, pour the lemon juice over everything, and mix. Serve immediately or store in the refrigerator for later.

Once, on a visit to my husband’s family, everyone got into a big discussion about some political topic or other, and my brother-in-law Ross asked what I thought. “I don’t know enough about that to have an opinion,” I responded. Ross started laughing and joked, “You’re supposed to say the OTHER guy doesn’t know enough to have an opinion!”

Some of us, aware of the intransigence and malfeasance of insurance companies, might say good riddance. Take the time my brother injured his knee playing basketball. His insurance company refused to pay up, because they claimed that his injury was a preexisting condition. After a time-consuming series of letters and phone calls, our parents had to threaten to report the company to the state’s Attorney General in order to get the bill paid.

Excess deaths is a better measure of the effectiveness of different interventions for two reasons. First, using excess deaths instead of Covid deaths removes the problem of how you categorize deaths with more than one possible cause. And second, lockdowns have also led to deaths from neglected healthcare, overdose, suicide, and murder.

I remember lining up in our elementary school gym for the “swine flu shot” back in 1977.

For example, when the Cochrane review found that mask mandates were ineffective, writers on the left rushed to tear down their conclusions without taking time to consider whether the review was correct. I wrote about it here.

My husband made up a blues song called “Justified True Belief,” which ends with, “I’ve got a justified true belief / that you should love me!” Whenever our kids would mention their Theory of Knowledge class, he’d sing it. I predict that when he reads this article he will start singing it again.

You have left out one of the main reasons why the United States doesn't have Universal Healthcare: racism. This NY Times article provides a good explanation of the history behind the issue: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/universal-health-care-racism.html. There are many people today, many of whom would personally benefit from Universal Healthcare, who would never vote for Universal Healthcare because it would benefit people who are not white. Racism has helped to create so many of the backward and harmful systems that exist in this country.