This is the first of two articles on academic tracking. This week’s article tells some stories and shares some thoughts about talent. Next week’s article will look at specific educational systems and what we can learn from them.

Everybody Is Talented, Because Everybody Who Is Human Has Something to Express

A man I knew when I lived in Prague, Kraig, likes to hang out in coffee shops and paint copies of old masters using the dregs in his cup for paint. As he says, “I studied classical painting but didn’t have much time for it until Covid. I love spending time in cafes, so I decided to combine two loves.” Here is a photo he took of one of his many paintings:

Ethan, the son of a grad-school friend, is in college at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. My friend often posts Ethan’s works (paintings, sculptures, and animations) on Facebook. Here is one awesome example:

Jana, whom I’ve known since we were toddlers, is a singer. Even back in high school she could toss off Handel arias, complete with ornaments and page-long sixteenth-note runs, as though they were “Hot Cross Buns.” She has toured the world as a backup singer for stars like Don Henley, Stevie Nicks, and Prince. Prince has even written songs for her.

A former choir director is a perceptive and brilliant musician with an extraordinary memory. When I sang Bach’s Mass in B Minor with him, he conducted it without a score.1

Two of my friends are fluent in four languages (and can speak a few others at an intermediate level), and one is fluent in five (English, Czech, Russian, German, and Spanish)—and many of the women I am friends with in Prague and Switzerland are trilingual.

Many years ago, I was at a gathering where one of the guests was an outdoor-adventure leader. Over the course of a fascinating ten or fifteen minutes, he recounted a kayaking trip down a whitewater river in precise detail, describing the turns, obstacles, rapids, vegetation, and animals he saw, where he saw them, and how he navigated around them. It was an amazing feat of visual memory—and of physical skill in keeping his kayak upright.

Warning: If you are squeamish, you should skip to the next paragraph. When my son was eight, he needed surgery on both his eyes, which required that his eyeballs be cut and sutured. As he was emerging from the anesthesia, he moaned in pain. A nurse sat with him, took his hand, and spoke with such calm confidence that she was able to soothe him and help him get through those first frightening moments.2

A college friend, while doing a problem set for his physics class, discovered an error in Newton’s Principia Mathematica—an error that had previously gone undiscovered for three hundred years. (Here is an interesting article about him.)

As for me, well, I am not in my friends’ league, but I have an extraordinary talent too, if I do say so myself: Finding things. For example, my mother-in-law once mentioned that she wanted to lend someone her copy of the fourth Harry Potter, but she couldn’t find it. The last time I had been in her house was a few months before, but I could immediately visualize where the book was: “It’s in the den, in the second bookshelf from the right, on the second shelf from the bottom, and I think it’s the third or fourth book from the left.” Which is exactly where it was.3

The Parable of the Talents and Public Education

In the parable of the talents (Matthew 25:14-30), a man is preparing to go on a long journey, and before he departs he entrusts his property to his three servants. He gives five talents (i.e. a hefty amount of money) to the first servant, two talents to the second, and one talent to the third. The first and second servants invest the money, but the third servant, fearing his master’s wrath if he loses the coin, buries it for safekeeping. When the master returns at the end of the year, he learns that the first and second servants have doubled his property, and he praises them: “Well done, good and faithful servant.” But when the third servant returns the single talent, the master castigates the servant for his laziness and wickedness. The moral of the story is that our talents are only worthwhile if we put them to use in the world.

In spite of its edifying moral, this parable rubs me the wrong way. For one thing, it is rather uncharitable to the third servant, who may well have a good reason for his risk-aversion and who may quite understandably not want to go to a lot of trouble only to enrich his master. Even worse, the parable assumes that we have all been granted the exact same talent, if in different quantities, and that if we exert ourselves in the exact same way, we will all flourish. Luckily, this assumption is false, because what an impoverished, conformist world it would be, were this to be true! Every single one of us has unique talents that we can contribute to the world, and our world is better off when we give everyone the appropriate opportunity to develop these varied talents.

Millions of children nationwide are returning to school after the summer break, so this topic is on my mind. While we readily acknowledge that musical, artistic, and athletic talent exists and ought to be nurtured, we are strangely reluctant to offer a similar benefit to academically talented children in our public schools. Academic tracking, in which children with strong abilities in math, science, language arts, and the social sciences take classes with more advanced content, has fallen out of favor and has been eliminated from many school systems. Educators who oppose tracking say that academically talented kids can spend class time tutoring the other children, and if they’re bored, they can always learn on their own. Dismissive statements like “those kids will be just fine” come up in these discussions all too often.

Not only is this reluctance to educate academically talented kids cruel to them, but it is also short-sighted for our country. We need doctors and nurses, mathematicians and scientists, coders and engineers, investigative journalists and historians, and teachers and lawyers—plus myriad other roles not on this list. To get people to fill these crucial roles, we need to challenge able students in our schools so that they will develop their special talents. It’s not enough to hope that they will figure it out on their own, nor is it fair to expect that their parents will pay for supplementary instruction. Or, put another way, what if we had this same “just fine” attitude toward, say, sports? Can you imagine how angry everyone would be if schools started denying star athletes adequate training and told them they were required to spend their practice time coaching the weaker kids instead?

A New Version of the Parable

If I were to rewrite the parable, here’s how it would go: For show and tell on the last day of school before summer, a teacher asks her students to bring in something that represents their special interests. Alex brings a bag of seeds, Chris brings a piggy bank full of coins, and Sam brings a palette of paints. The teacher knows that these children require different instruction in order to bring their gifts to fruition. If they all bury their gifts, like the third servant in the original parable, only the seeds will grow. If they all try to invest their gifts, like the first two servants in the original parable, only Chris will make a profit. And if they all spread their gifts on paper, only Sam will create something beautiful.

Instead, the teacher educates the children appropriately to their interests and talents. At the end of the summer, when the children return to school, everyone is rewarded: Alex offers the class a cornucopia of flowers and vegetables, Chris treats the class to an ice cream party funded by her summer earnings, and Sam decorates the classroom with his art.

The talented people in my own life were fortunate to have had teachers who educated them according to their interests and talents too, and we are all the beneficiaries. Kraig’s coffee paintings will be published in November, in a collection titled Coffee with Mucha. For more about Kraig, and to see a photo that shows why he is Prague’s favorite natural-bearded Santa, you can visit his website here.

Ethan continues to study art at the SAIC and to create his wonderful pieces. If you are interested in seeing more of his art, you can find him on Instagram here, or at his online store here.

Jana entertains thousands of people in the Twin Cities with shows that pay tribute to female musicians, including Joni Mitchell, Carole King, and Olivia Newton John. In her home studio, she is teaching a new generation of singers.

The choir director founded the professional Chicago Chorale and has been its artistic director for more than twenty years. He continues to enrich the lives of singers and audiences alike.

My multilingual friends make authentic connections with people from around the world, with whom they literally speak the same language. Many are teachers too.

The college physicist went on to get his PhD in physics and now helps to advance scientific knowledge as the managing editor of Physical Review Letters.

I continue to help friends and family find lost objects. My talent for noticing and interpreting small details was nurtured by my English teachers, which has helped me be a teacher, editor, and writer.

I am no longer in touch with the outdoor adventure guide or the nurse, but I am sure that they are still leading people through the wilderness and out of surgery in safety and comfort.

How about you, readers? What are your special talents, and who helped you to develop them? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Over the past few weeks I seem to have delegated tidbit-selections to my daughter, among whose many talents is finding fascinating, informative, and uplifting videos to share. In the video below, the mathematician and musician Vi Hart arranges the round “Dona Nobis Pacem” (known to anyone who has ever sung in a choir or gone to summer camp), for voice, piano, and triangle. She and the mathematician Henry Segerman film it with a special camera so that the three separate performances take place in a single, continuous space. The music is beautiful and features my favorite musical trope, the deceptive cadence. Enjoy!

In this next video, Hart and Segerman explain the mathematics behind “Peace for Triple Piano,” as well as how it was filmed, edited, and choreographed. I have to confess that much as I love math, the math in this video is over my head, but I enjoyed it nonetheless, and you will too!

Readers who are not musicians may not know that conducting without a score is extremely rare, even among professional conductors. As far as I know, of all the top conductors in the world, only Pierre Boulez, Arturo Toscannini, and Herbert von Karajan routinely conducted without scores. The score for the Mass in B Minor, for example, is about 250 pages long, and the mass is composed for chamber orchestra, soloists, and 8-part chorus. A conductor would need a near-photographic memory in order to be able to conduct it accurately without the score.

I wrote a letter to the nurse’s supervisor to make sure that our gratitude for her help and support were noted in her file.

I also have the talent of being able to banish all clouds through the simple expedient of forgetting my sunglasses at home, a talent I have used to good effect on my hikes.

For lack of a better place to put this citation, I will note here that this section’s heading is a quotation from the Minnesota author Brenda Ueland.

This reminded me of a story about my mother. When I was in 5th Grade during a parent/teacher conference the teacher was saying how great it was to have me in the class because she could use me to help with the other kids. My mother asked where my paycheck was.

I think that story manages to summarize my agreement with this as well as sum up my mom.

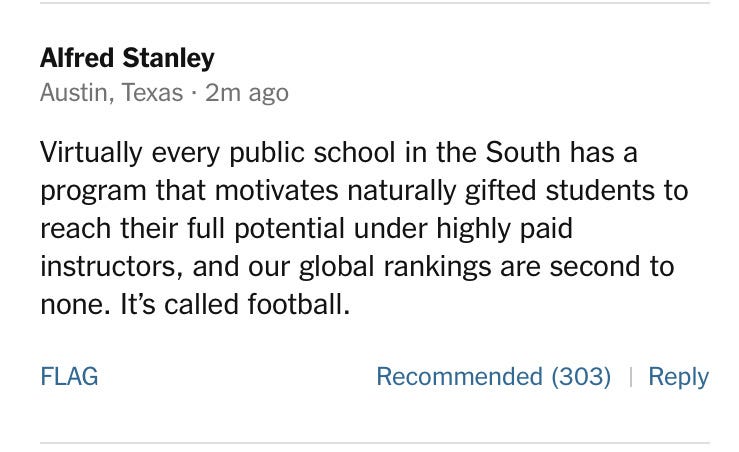

You make a valid point. I was thinking about this--no one would want a surgeon who wasn't smart, or a lawyer, or a civil engineer, etc. And yet, as a nation we reject the idea that intelligence is something to be nurtured. People have different talents. Some are good at running with footballs, others at figuring out how to treat a person's disease. Myriad talents all requiring support.