Last week we explored Moral Foundations Theory by looking at a single ethical puzzle. If you haven’t yet read that post, you can find it here:

As a quick reminder from last week, here are the five moral foundations,1 which we’ll be discussing in this week’s post:

Care vs. harm

Fairness vs. cheating

Loyalty vs. betrayal

Authority vs. subversion

Sanctity vs. degradation

You may already have a pretty clear idea which moral foundations you think are most important and which you deemphasize or reject, but if not, here is a short questionnaire, developed by Jesse Graham and Jonathan Haidt. You might find it interesting.

A (Slight) Disagreement with Haidt

In his book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion, Jonathan Haidt takes on a herculean task in our polarized times: He attempts to help Americans of all political persuasions understand each other better. Haidt argues that all political positions arise from our commitments to what we believe is moral. According to Haidt, our differences result from a misunderstanding: While people on the right side of the political spectrum value and live by all five moral foundations, people on the left emphasize the care vs. harm and fairness vs. cheating foundations far above the other three. So when we fail to understand and agree with each other, in Haidt’s view, it’s because we are arriving at our political positions from different assumptions about what is moral. Haidt’s hope is that if we better understand the moral foundations of people’s political positions, we will have more respectful and productive discussions.

I think Haidt is right to encourage us to understand each other better, and his Moral Foundations Theory can help us to avoid the Fundamental Attribution Error so that we stop attributing evil motivations to people with whom we disagree. Moral Foundations Theory reminds us that nearly all of us are acting out of good intentions and are trying to make the world a better place. I depart from Haidt, though, in that I think that all Americans, of all political persuasions, sometimes value and sometimes reject all five foundations, depending on the situation and the issue.

Who knew that bananas were berries? Whether it’s berries or people, whenever we try to generalize and impose categories, we discover that things are more complicated than we had thought. As I said in my title, we are only human: All of us, ideally, try to care for others, to be fair and loyal, to respect authority, and to be pure of heart—and at times we are all guilty of harm, cheating, betrayal, subversion, and degradation. It’s easy2 to find examples from the news of people following or rejecting all five foundations, regardless of their politics.

We Have the Same Goals but Disagree about How to Achieve Them

When I was in college, I had a friend who was a Chicago School economist and a Libertarian acolyte of Milton Friedman—while I am a proud occupant of the left wing of the political spectrum. We argued about everything. Once, after a tiresome and unproductive debate about school vouchers, he said, “Can you agree that we have the same goals, but we disagree about how to achieve them?” I realized that at least in that case he was right.3 I have tried to keep this idea in mind in all of my conversations, so, accordingly, I will be steel-manning political positions below that are different from my own.

Care vs. harm. This moral foundation is most often associated with the political left. The left believes we should expand the social safety net to provide Americans with universal healthcare, affordable childcare, paid family leave, and similar benefits that are normal in most other developed countries. People on the left care for those who are less fortunate by advocating for public programs as well as by donating to private charities.

Even though conservatives tend to oppose publicly-funded social-safety-net programs, they care for people too, not only through private charities but also through their churches: From a Christian perspective, proselytizing is a way to care for people. When I lived in Prague, I had a friend who was a Jehovah’s Witness. Just before I moved away, she gave me a Jehovah’s Witness Bible because she was worried about my soul and wanted to share her faith with me. Similarly, the daughter of another friend recently went on her Mormon mission and wrote about her experiences with the people she met, most of whom were coping with many challenges, including poor health and poverty. She shared religious teachings, friendship, and a listening ear with people who were otherwise isolated and unheard.

Fairness vs. cheating. We associate this foundation with the left as well, particularly on economic issues. The left points out that it isn’t fair that poor people pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes than rich people, or that income earned through work is taxed at a higher rate than investment income, or that social security taxes are assessed on only the first $147,000 of income (people pay zero social security taxes on income above that). The left also supports labor unions and a higher minimum wage in the hopes that that will make the economy fairer for everyone.

However, the right values fairness too; Arlie Russell Hochschild, in an interview about her book Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right, gives us an eloquent version of the right’s “deep story” about fairness:

Think of people waiting in a long line that stretches up a hill. And at the top of that is the American dream. And the people waiting in line felt like they’d worked extremely hard, sacrificed a lot, tried their best and were waiting for something they deserved. And this line is increasingly not moving, or moving more slowly.

Then they see people cutting ahead of them in line. Immigrants, blacks, women, refugees, public sector workers. And even an oil-drenched brown pelican getting priority. In their view, people are cutting ahead unfairly.

Loyalty vs. betrayal. I think we can agree that in our private lives, everyone values loyalty—to our families, friends, and communities. I would love to go one step further and retire the stereotype that only the right side of the political spectrum is loyal to our country. As Jon Stewart has said to Trump supporters, “You don’t own patriotism!” Those of us who are on the left just express our patriotism differently. While the right may feel frustrated that liberals emphasize our country’s flaws and seem reluctant to express wholehearted pride in America, the left believes that the best way to show loyalty to our country is to hold it to a high standard. If that means criticizing America, so be it. After all, it was Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the people who fought for civil rights, and not Bull Connor, who helped make America a country worthy of our loyalty.

Authority vs. subversion. When I was in grad school, a friend came to a sudden realization: “When did we start assuming that ‘subversive’ is always a compliment?” she asked. And it was true: When we wanted to bestow the very highest possible praise on a person, work, or idea, we (and everyone we knew) would call it subversive. So the stereotype that people on the left prefer subversion to authority strikes me as fair, especially when compared with the right’s respect for hierarchies, whether within the family or in public life.

Nonetheless, people on the left respect authority too. Think of liberals’ respect for those who gained their authority through experience and education—for example, climate scientists and medical researchers. And reports of the death of respect for authority on the left have been greatly exaggerated in many other cases too. As just one instance, I was struck recently by how eloquently Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson honored her country, her mentor Justice Breyer, her family, her church, the military, and her forebears in her speech accepting her nomination to the US Supreme Court. The quote that follows is just the opening to her speech, but I encourage everyone to read or listen to the whole speech for a powerful expression of gratitude and respect for authority as spoken by a prominent person on the left:

I must begin these very brief remarks by thanking God for delivering me to this point in my professional journey. My life has been blessed beyond measure, and I do know that one can only come this far by faith.

Among my many blessings—and indeed, the very first—is the fact that I was born in this great country. The United States of America is the greatest beacon of hope and democracy the world has ever known.

I was also blessed from my early days to have had a supportive and loving family.

At the risk of sounding tautological, I have to conclude that we all respect those authorities we deem worthy of respect, and we all want to subvert those authorities we don’t.

Sanctity vs. degradation. This foundation is concerned with purity and pollution; its adherents attempt to separate themselves from those practices, substances, and people they believe are contaminating. Rules about sexual morality are probably the most familiar expression of this foundation. However, the sanctity foundation also includes (among many other examples) the Laws of Family Purity in Orthodox Judaism; dietary restrictions in such religions as Judaism, Islam, and Hinduism; abstention from alcohol in Islam and many Christian denominations; funeral practices and rules for mourning; and ritual washing before prayer.

Because this foundation is so important in fundamentalist religions, most people—and not just Haidt—consider it the sole provenance of the political right. However, the left has its own expression of this foundation. We see it in strict environmentalism, which opposes GMOs and nuclear power and encourages people to eliminate fossil fuels, plastics, and chemicals from their lives. Vegans, especially those who comb over ingredient lists to ensure that they don’t ingest any traces of animal products, are also expressing the sanctity foundation’s importance to their morality.

And, conversely, it is clear that not everyone on the political right believes in sanctity or is opposed to pollution when it comes to Mother Earth. “Rolling coal” is one example: Some right-wingers, in an effort to demonstrate their contempt for climate science, have modified their trucks so that they fart out nasty fumes and pollutants into the atmosphere and into our lungs (forgive the vulgarity, but “belch” is too polite a word for this foul behavior; besides, the fumes come from the back end of the trucks).4

Instead of Invective, an Invitation

You will notice that with the exception of rolling coal, I haven’t given any examples of people—whether left, right, or center—violating the five moral foundations. You may have in mind a number of cases where the other political side is guilty of harm, cheating, betraying someone or something, showing disrespect for authority, and degrading something that should be pure. I can think of examples too, and I could easily have filled this essay with invective. Instead, I prefer to offer an invitation: Let’s think about how we have all fallen short and have failed to live up to our ideals along the full range of moral foundations, from caring for others to living a pure life. A wise teacher once said that we should stop worrying about the speck in our neighbor’s eye and worry instead about the board in our own. While I think it’s normal and ok to worry about—and to attempt to remove—the speck in our neighbor’s eye, we will be more successful in our efforts if we keep our own flaws—and other people’s virtues—in mind. The problem with all of us is that we’re only human—but our humanity is also the solution, so long as we ask ourselves before we act or speak, “Am I being caring, fair, loyal, and respectful? Am I adding to the evil or to the good in the world?”

What do you think, readers? Which moral foundations do you value, which are less important to you, and which do you reject—and why? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Another framework for thinking about our political differences, with which most readers are likely familiar, is the political compass:

To return to our ethical puzzle from last week, I would place Allan in the Libertarian Right quadrant, David in Authoritarian Right, and both Caroline and Edward in Libertarian Left. Do you think that makes sense?

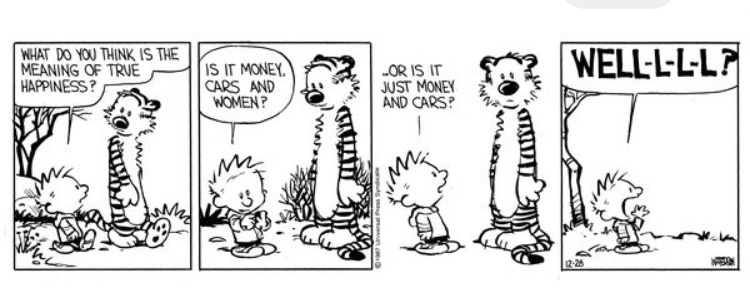

A couple of years ago, my son (very cleverly, if I do say so myself) illustrated the political compass using Calvin and Hobbes cartoons. I’m reproducing it here with his permission. Which quadrant are you in? (The title of this essay should give you a clue where I belong!)

Here’s Authoritarian Right:

Here’s Authoritarian Left:

Here’s Libertarian Left:

And here’s Libertarian Right:

For simplicity’s sake, and because I don’t want to wade into the morass of Covid debates, I won’t be discussing the proposed sixth foundation, liberty vs. oppression.

In fact it’s so easy to think of examples that I feel as though it’s not a fair fight. I’m reminded of a high school debate tournament I once chaperoned, where the negative team had a much easier task than the affirmative team. The question for debate, “Resolved: Intellectual ability is able to flourish only in conditions of economic plenty,” could have been won for the negative team with a one-word counterexample: Ramanujan.

In spite of my best efforts, I remain suspicious of his motivations for wanting to abolish the minimum wage, though.

I have to share a funny story: In 2015, a guy modified his truck to roll coal. He catcalled a woman, she ignored him, and in retaliation he spewed soot and poisonous fumes all over her. Turns out she was an off-duty police officer, and so his truck was impounded and he faced criminal charges. Oops! He was not expecting that! Heh heh heh.

I quite like this post--the invitation to openness. My number one value is probably caring--people like that are drawn to the helping professions, like nursing. What really struck with me while reading this, though, is how many schools of nursing embrace, tacitly or not, authority as the highest value. Nursing professors are supposed to be teaching care vs. harm--a literal proposition in health care. But the unspoken curriculum is obedience vs. disobedience, or authority and its evil twin, power. This is true of the history of nursing and it really needs to change, in part because it creates toxic work environments, but also because that focus keeps nurses from banding together to make the profession better for all. I don't think that care and authority are intrinsically in conflict, but in some nursing schools they are, even though "caring" is held up as ostensibly the highest value. That is a very bad paradox in terms of creating a mentally healthy health care system.

I think it was Robert Sapolsky in "Behave" (if it wasn't from there I apologize, but I always like to recommend this book) looking at the part of the brain that registers disgust. He noted that people sensitive to disgust tend to be conservative. Seems intuitive.

He described a study of participants taking a quiz that rated how conservative they were. Then they put rotten food in a nearby garbage and it raised the levels of everyone.

I take these kind of studies with a grain of salt, but it seemed helpful to me in imagining how my conservative friends experience the world.