Last week’s Labor Day post was about healthy workplaces, in which bosses show gratitude for their workers’ contributions and encourage them to develop their potential. This week’s post focuses on workplaces that demand free labor from their employees. I’ll argue that this is an unhealthy practice that we ought to resist.

I’ll begin with a personal story, in which I do not come off well. Many years ago, my daughter attended public kindergarten, which officially ran from 9 to 11:45am. Our school district didn’t employ paraprofessionals (paras) outside of school hours, and parents weren’t allowed in the building to help our kids get situated, out of their coats, and ready for their day. So we would all hang around the playground, and on the very dot of 9am, and not one second before, the teachers would come outside to shepherd their charges into class. By the time the kids were in their classrooms, unpacked, and in their seats ready to learn, it was usually about 9:20. Then, around 11:25, the teachers would stop teaching and have the kids pack up. They would lead the kids downstairs early enough that they could be released to parents on the very dot of 11:45, and not one second after.

Attentive readers will notice that the kids’ actual learning time was just over two hours per day. I felt as though the kids were being cheated out of some of their already very limited instruction time, and I made dark remarks to other parents about the teachers’ “work-to-rule” strike. Most families in our town were well-off, so it was common for families (ours included) to pay for private wraparound classes at the YMCA, JCC, and local churches.1 But kids from families who couldn’t afford these classes were stuck with a truncated school day. I spent the year resenting the teachers for not putting in the extra time and effort we typically expect from them.

The irony is that when I was a teacher I regularly put in sixty-hour work weeks, and, needless to say, I was only being paid for forty. And these weren’t relaxed hours of chatting with colleagues, taking coffee breaks, and surfing the internet. My days were filled with emotional and intellectual intensity and were so crowded with tasks that I rarely had time to eat lunch or even go to the bathroom. I didn’t appreciate having to work those twenty hours for free every week, so why did I forget Hillel’s wisdom, “That which is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow,” when it came to my daughter’s teachers?

The Shame of Quiet Quitting

Well, one reason I blamed the teachers for refusing to work for free is that I was caught up in some destructive ideas many Americans hold about work and compensation. One such idea is that because people in the helping professions—teachers, nurses, public-interest lawyers, primary-care doctors, and the like—get satisfaction from doing good in the world, these workers ought to be grateful that they have a meaningful job and not be “greedy” about their pay.2 It’s as though warm fuzzies were a legitimate form of compensation. Unconsciously, I believed that the teachers should have enjoyed volunteering their time to supervise my daughter and her classmates outside of school hours.

More generally, we Americans suffer from workism, the belief that work is “the centerpiece of one’s identity and life’s purpose,” and that we attain meaning not through our relationships with other people, but through our achievements at work. We submit to the demands of hustle culture, “overworking on purpose—and boasting about doing so.” It is common for employers to expect workers to arrive early and stay late, to work through the weekends, to come in sick, and to let vacation days accumulate, unused. Our culture sneers at—and employers don’t hire or promote—workers who leave the office at 5pm. Some of us think of a sensible work-life balance as “quiet quitting,” or, worse, a “lazy girl job.”

In fact, the ones who should be ashamed are not the workers—who are fulfilling their end of the bargain, after all. Why don’t we look askance at employers who are trying to get something for nothing? Why do we call it “quiet quitting” when workers are doing the jobs they are being paid for? This is actually the opposite of quitting! And yet somehow it has become a radical idea that we should pay people for all the work they do.

Free Labor Is a Negative Externality

A negative externality is a cost that is incurred by one party but imposed on someone else. A classic example of a negative externality is the pollution that results when companies cut corners on environmental safety. The companies profit, and innocent people suffer. Our current work culture, in which employers expect workers to donate some of their labor, puts all the costs of poor business decisions onto the least powerful among us—individual workers—and awards all the benefits, in the form of lower taxes and increased profits, to the richest among us—people in the top tax bracket, business owners, and shareholders. If ordinary Americans were no longer made to work for free, not only would workers enjoy more leisure time with their families, but businesses would be forced to make a number of improvements that would benefit society as a whole.

Most obviously, without free labor, employers would have to hire more workers to do the additional work. Americans across the political spectrum ought to support policies that create more jobs. To return to my personal example, why didn’t our school district hire paras to supervise students before and after school? Our town could definitely have afforded to hire these workers. The year my daughter was in kindergarten, the town had embarked on the expensive boondoggle of installing Belgian-block curbing on every street in town, to the tune of millions of dollars.3 If the town had chosen to repair curbs only when necessary and using normal concrete instead of expensive stone, they could have put the money they saved toward hiring paras—good jobs for people without college degrees.

Hiring sufficient workers would also improve safety. One cause of the deadly Ohio train derailment was that the railroad hired only three workers to handle a nonstop, 149-car, mile-long freight train. Or take nurses. In an effort to cut costs, many US hospitals hire fewer nurses than their patients need. This forces nurses to skip breaks, work through lunch, and stay late, unpaid.4 When hospitals rely on the free labor of too few nurses, they endanger patients. As this report from the NIH finds, “Nursing shortages lead to errors, higher morbidity, and mortality rates. In hospitals with high patient-to-nurse ratios, nurses experience burnout, dissatisfaction, and the patients experienced higher mortality and failure-to-rescue rates than facilities with lower patient-to-nurse ratios.” A 2006 study showed that if hospitals hired enough nurses, “5,000 in-hospital patient deaths and 60,000 adverse patient outcomes could be avoided” every year.

Next, because employers currently foist the costs of their inefficiencies onto their workforce, they have no reason to invest in improvements. If employers were the ones who had to pay, they would be incentivized to make their systems more streamlined and rational. Below are four examples of workers who pay the costs of inefficient systems; I’m sure readers can think of many others.

First, medical professionals put in untold unpaid hours every day filling out electronic health records (EHRs) and other documentation, using kludgy, unintuitive software. As this article notes, “Some practices have separate EHR, quality reporting, billing, and population management systems. Other EHRs tie functions together, but even those may require physicians to double and triple document certain aspects of care.” A doctor friend has complained, for example, that the electronic chart used at his hospital requires him to input scads of irrelevant data for all his patients, every time he sees them. Why can’t the chart store the data? If the hospital had to pay him for this clerical work, you can bet that they would invest in creating a simpler, more logical electronic charting system.

Second, flight attendants, as most readers know, are not paid for their work when the airplane door is open. But if the airlines had to pay them for the time they spend helping passengers board, stowing cumbersome luggage before the flight, and retrieving it at the end, the airlines would be motivated to change their policies to make boarding quicker and more efficient, to the relief and delight of passengers everywhere. The airlines might finally decide to do the sensible thing and charge for carry-on luggage while making checked luggage free. (Readers who are not yet familiar with this hobby horse of mine can read about it here and here.)

Third, workers at Amazon warehouses have to endure long security lines before and after work; they sometimes have to arrive at work as much as half an hour early in order to clock in. Amazon is perfectly capable of coming up with a better way of handling this. I am just an unfrozen caveman lawyer, but even I can imagine an app that workers could use to check in—they could turn on location services when they arrive and click a button, rather than waiting in line. And if Amazon is worried about workers absconding with stolen goods, they could do random spot-checks or, heck, install the kind of scanners we see at store exits, rather than requiring that every worker donate a few hours a week waiting in their security lines after work.

Fourth, as every white-collar worker knows, every day millions of Americans have to sit through tedious meetings that could have been an email—or dispensed with altogether. These meetings consume time that workers could use to perform the rest of their duties during normal working hours. Employers: Stop holding these meetings! No one will miss them!

Finally, if employers were required to pay workers for all the work they do, they would be incentivized to omit needless tasks (to paraphrase Strunk and White). To illustrate this point, I’ll close by focusing on another personal example, from my time as a high school English teacher. My duties included developing courses, planning lessons, classroom teaching, grading, counseling students, and meeting with parents and other teachers. It was impossible to do all this work in a normal forty-hour week, but I didn’t really mind. I loved my students and wanted to help them become the best writers and thinkers possible, to encourage them to love literature, and to support them in their social and emotional development.

In addition, though, my job required a number of extra, unpaid, tasks, which pushed my work weeks up to and beyond sixty hours. I ran clubs,5 participated in hours-long quarterly meetings in which we discussed every student in the school in detail, attended weekend and summer professional development sessions, chaperoned dances, wrote letters of recommendation for nearly every senior in the school, wrote page-long essays about all my students for their parents three times a year,6 and read and judged hundreds of submissions for twice-yearly writing contests.

Obviously, many of those extra tasks were crucial to the job and well worth additional compensation (writing letters of recommendation, for example), while others (for example chaperoning) could be easily paid for with a small honorarium. But all those essay-length comments multiple times a year? The writing contests? The hours of meetings to discuss students I had never even met? If the school hadn’t gotten that labor for free, they might well have decided that those extra tasks weren’t worth the money, and we teachers would all have been better off, at no cost to our students.

There Is Power in a Union

Let’s sing along!

I sometimes feel as though I am a lone voice crying in the wilderness when it comes to the expectation that Americans provide their employers with free labor, because this norm is so entrenched in our culture. Besides, Congress is unlikely to enact legislation banning it anytime soon. (In fact the article I linked to above reports that some workers sued to get Amazon to pay them for waiting in those ridiculous security lines, but the Supreme Court ruled against them.) Alas, it looks like we can’t expect our elected leaders to help us with this problem. But in our own lives we can come together and act. A first step is recognizing that this free-labor expectation exists, is pernicious, and ought to be resisted. Then, as employers, we can commit to paying our workers for all the time they put in. We can stop expecting our direct reports and colleagues to work outside of normal business hours. And, as employees, we can join together in refusing to give our bosses extra work unless they pay us for it. Together, we can resist hustle culture and restore balance to our lives.

How about you, readers? Have you ever had a job where you were expected to work for free? Or have you ever found yourself placing that expectation on someone who worked for you? What happened? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

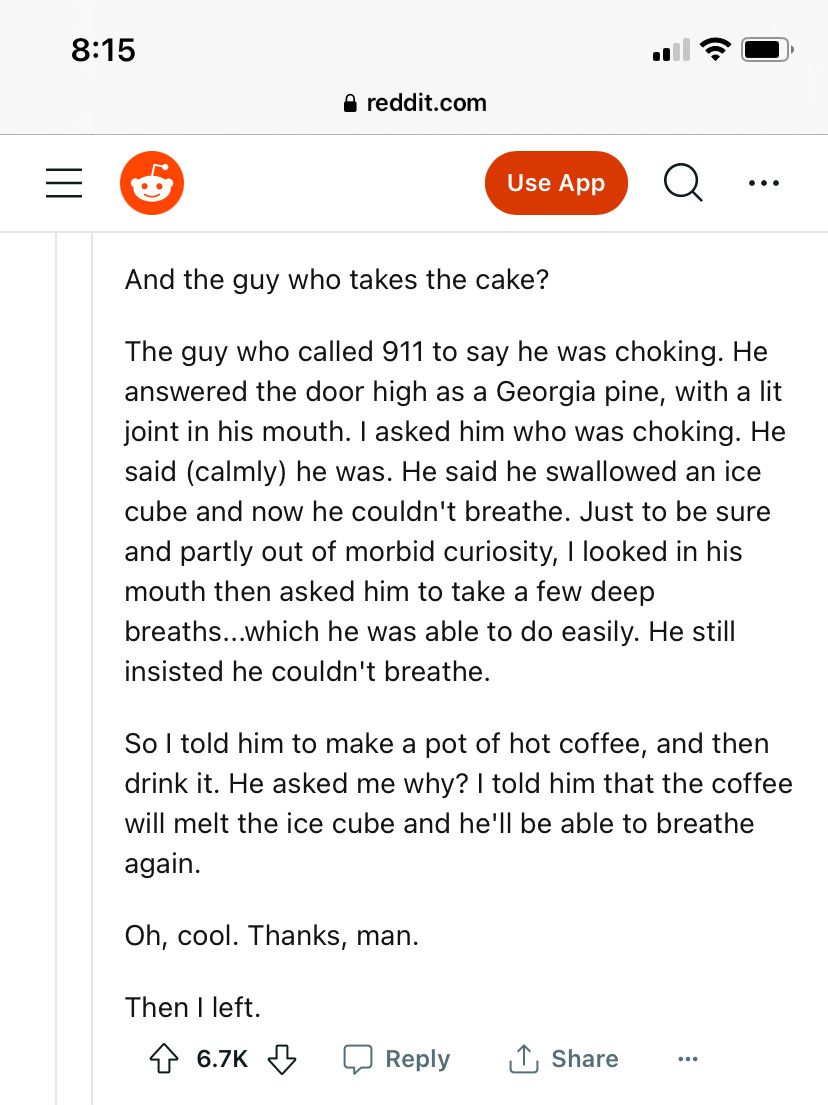

Speaking of medical professionals, I recently ran across a Reddit thread that asked, “Have you ever had a patient so lacking in common sense you wondered how they made it this far. If so, what is your story?” Most of the stories were depressing evidence of the woeful state of sex education in many parts of the US. However, there were a couple of gems, for example this story:

Whatever they are paying this EMT, it is not enough.

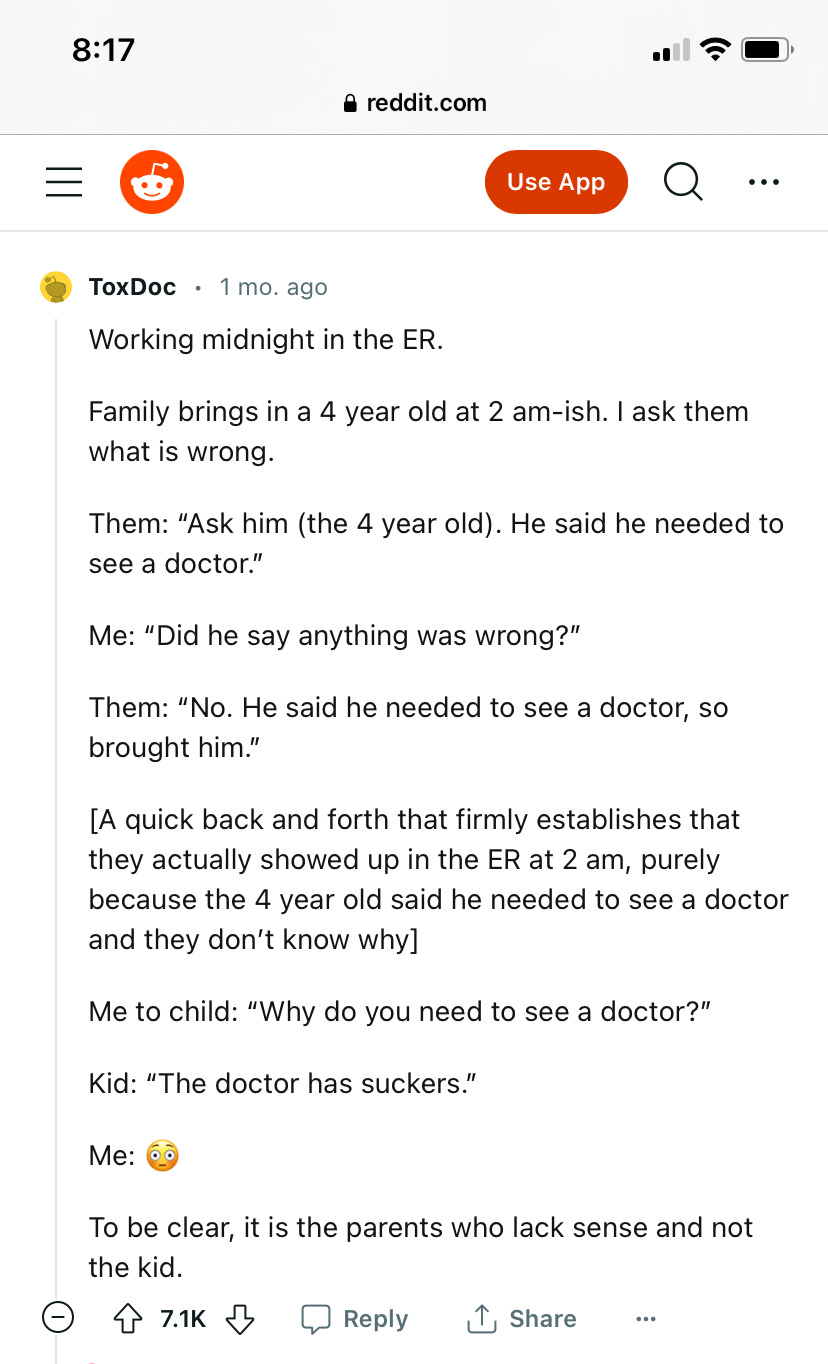

Or how about this doctor? I have no idea how he managed not to burst out laughing at these people:

Do you think the kid got a sucker? I hope so!

My wonderful mother-in-law, as a birthday gift to me, paid for our daughter to have bus service from the public kindergarten to the private wraparound, so that I didn’t have to rush back to the kindergarten every day to pick her up and drive her across town. This is one of the most thoughtful gifts I have ever received. Thanks, Louise!

On this topic, I highly recommend David Graeber’s excellent book Bullshit Jobs: A Theory.

My dad’s first comment when he saw the Belgian-block curbing was to wonder whose brother-in-law owned a granite quarry.

On this topic, I highly recommend The Shift: One Nurse, Twelve Hours, Four Patients’ Lives, by Theresa Brown, RN. Brown’s entertaining, affecting, and well-researched book discusses how understaffing threatens patients’ health, contributes to nurse burnout, and worsens staff shortages.

I taught in a private school. Most public schools pay teachers for the extra work of running clubs, coaching sports, directing the play, etc. Hooray for unions!

It could be worse. This article mentions a school that requires its teachers to call every parent, every day. Every parent! Every day! I’m sorry, but that is insane.

Thanks for bringing my book THE SHIFT into your great column, Mari. As a nurse I really minded the creep of uncompensated time. We were hourly employees, but expected to check email when not at work and keep up with updates for our hospital floor and sometimes attend inservices, all without compensation. So, the expectation was that we were available 24/7 and our time off was never really our own and we were not going to be compensated for that extra time. That is wage theft and exploitation plain and simple. You point out all the dangers of nurses being overworked. Part of why nurses are quitting is the lack of personal/professional boundaries in health care. We are not indentured servants and should not be treated as such.

You struck a chord with me, obviously. I really hate the American idea that work=life, and post breast cancer I have chosen to reject it. I'm lucky in that I'm an author and paid speaker and so have other ways of earning money. A lot of nurses, teachers, Amazon workers, etc. are not so fortunate and have to choose between exploitation on the job and not being able to pay their rent, care for their kids, eat.

This topic has always been dear to my heart, thanks for the perspectives. Bottom line is that I agree our society should learn to adopt expectations that work time has limits, and that people get paid fairly for their time. It's a tough sell here, but some noises about moving to a 30-hour work week might help the discussion.

I found over the course of my few careers that it's most effective to start good habits on day one of a new job. Come in on time, work hard, and leave at 5 PM with your head held high and no excuses. This probably worked for me as I had jobs which were technically skilled and couldn't be quickly replaced. When I had "on call" jobs where I routinely had to work nights and weekends, I did so reliably. But when the boss would ask me to work other times "to help out" I flatly refused and said my on call times where set, and when not on call, I wasn't at work, period. One boss once gave me a not-so-veiled threat that my future career there might be in jeopardy if I didn't pick up a spare project. I replied "Well, then let me make this easy for you, I quit!" (Isn't that everyone's fantasy to do just once?)