I once read about a study on kids and leadership.1 The researchers put a bunch of kindergarteners through a little test and then followed the kids for the rest of their school careers to see how they turned out. For the test, the experimenters put a hula hoop on the classroom floor and gave each child a beanbag. Then, they called the kids in one by one. They asked each child to stand a few feet away from the hoop and try to toss the beanbag into the hoop. Next, they asked the child to back up a few feet and try again, and so forth, until the child was almost at the edge of the classroom. For the final toss, the experimenters told each child that s/he could stand anywhere in the classroom s/he chose.

Let’s take a poll: Where would you stand?

As you have no doubt guessed, the vast majority of the kids walked right up to the hula hoop and dropped their beanbag in. Only a select few backed up those last steps to stand as far from the hoop as possible so that they could challenge themselves. The researchers found that the kids who challenged themselves in this exercise later turned out to be remarkably successful students and natural leaders.2

So What Is the Growth Mindset Anyway?

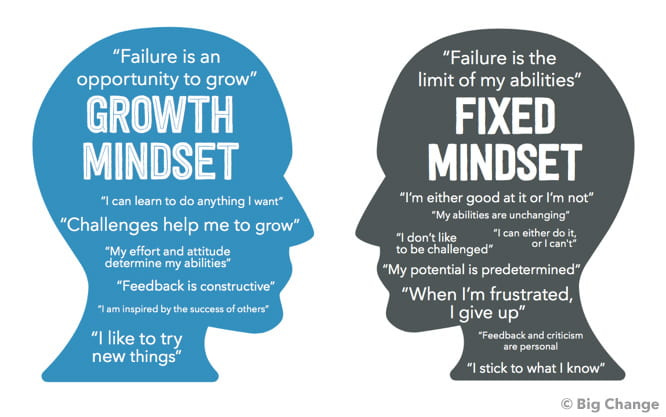

The growth mindset, as promulgated by the psychologist Carol Dweck, is the belief that we can become more intelligent and achieve great things if we think we can.

People with the growth mindset have the resilience to overcome setbacks and persist in the face of obstacles. In the little test at the opening of this essay, kids with the growth mindset will choose to stand as far from the hula hoop as possible, for the sake of the challenge and because they don’t fear mistakes. By contrast, according to Dweck, people who have the fixed mindset are easily defeated and take the easy way out. The fixed-mindset slackers are the kids who walk right up to the hula hoop and just drop their beanbag in. Michael Jordan makes a good case for the growth mindset when he says, “I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed”:

It seems obvious that we should encourage the growth mindset in everyone, and in fact many researchers in psychology and education view it as a silver bullet for success. For example, the article accompanying the tendentious illustration below promises that “By adopting this [growth] mindset, you’ll unlock your ability to improve your academic performance, and you’ll understand why it’s possible to go from C’s in high school to A’s in college.” All we need to do to get middling students to earn As is to instill the growth mindset in them? What is this sorcery?

As the inspirational posters in school hallways and classrooms throughout the country indicate, the growth mindset has become popular in education. Every year administrators, teachers, parents, and children attend trainings that aim to develop it. Kids are told that when they have trouble with schoolwork, they should remind themselves that they are capable of success, and they should keep trying. Parents and teachers learn that

The feedback that teachers give their students can either encourage a child to choose a challenge and increase achievement or look for an easy way out. For example, studies on different kinds of praise have shown that telling children they are smart encourages a fixed mindset, whereas praising hard work and effort cultivates a growth mindset.

Our kids’ school ran several of these trainings, and I attended the one offered to parents. Because of the training, I started praising my kids’ hard work rather than their intelligence and found . . . that this had basically no observable effect on their personalities, work ethic, or academic achievement. Their reaction to my little pep talks was more along the lines of, “Um, ok? Thanks?”

So What’s Not to Like about the Growth Mindset?

The growth mindset is obviously real, and, just as obviously, it is an advantage to be optimistic about our abilities, to be willing to learn from our mistakes, to accept criticism with grace, and to persist in the face of obstacles. So how is it possible that the growth mindset hasn’t been replicated? Well, it turns out that my experience with growth-mindset training is typical; what has failed to replicate is not that the growth mindset exists and is useful, but rather that it can be taught. There is no convincing evidence that growth-mindset training leads to academic improvement—and still less that it can convert high school C students to college A students. It seems more likely to me that our levels of growth mindset are innate and vary tremendously from person to person. Some of us just naturally have it in spades, while others of us struggle, and trying to convert the latter group into the former by running seminars and shifting how we praise kids is an exercise in futility.

I highly recommend this episode of the podcast The Studies Show, which debunks the research that claims to demonstrate the value of growth-mindset trainings.3 When studies are adequately controlled, follow ethical research practices, and have sufficient participants to ensure statistical significance, the effect of these trainings disappears. For example, a 2018 meta-analysis of 43 studies on the effectiveness of growth-mindset training found that there was a 96.8 percent overlap between the control and treatment groups, or “it’s roughly saying that there’s about a 3 percent chance it will have made an appreciable difference” (this discussion begins at 20:00).

This 3 percent chance may already seem tiny, but a 2023 meta-analysis, which looked at the original 43 studies plus 20 more, found a 98 percent overlap between control and treatment groups. Moreover, when the meta-analysis examined only preregistered studies, or studies that performed manipulation checks, or studies that were blinded, it found that growth-mindset trainings had no effect whatsoever (this discussion begins at 34:30). Most damningly of all, the meta-analysis found that “authors with a financial incentive to report positive findings published significantly larger effects than authors without this incentive” (this quote is at 43:40).

So What Should Parents and Schools Do Instead?

I’ll admit my bias: I am utterly lacking in growth mindset. I would have been one of those kids who walked right back up to the hula hoop for the final toss. Of course, I am horribly nearsighted, which wasn’t discovered until I was a teenager,4 so the beanbag toss would have been much harder for me than for other kids. Perhaps I would have demonstrated growth mindset if the researchers had chosen to test kids’ ability to sight-read Mozart on the piano. But I digress. One problem with growth-mindset training is that it can be victim-blaming. Instead of telling kids that they need to change their attitude, we adults ought to consider changing ourselves, our systems, and how we work with kids.

We can improve our teaching. When I was in college, I signed up for Introduction to Logic, because I have always loved logic puzzles like “Bob lives in a red house, Susan takes the bus to work, and Lisa’s birthday is in the summer. Which family owns the dog?” Turns out that formal logic is nothing like these puzzles—it’s much more like pure mathematics—and the class was utterly baffling to me. The professor would assign incomprehensible problem sets but offer no instruction or guidance. At the start of each class, he expected us to go up to the board and explain the proofs to each other while he sat off to the side, and he got angry at us when we were confused. I dropped the course. Yes, I lack stick-to-it-iveness, but the professor was also a bad teacher.

The vast majority of teachers are not like this professor, thankfully. They care deeply about their students and want them to learn. But sometimes school systems get stuck in faddish theories that lead to ineffective teaching. When students aren’t learning the material, before we blame them or tell them they just need to try harder, we ought to try different ways of presenting the material—giving up on whole language and teaching phonics instead, to take a recent, notorious, example.

We can eliminate senseless requirements from the curriculum. When I was in fourth grade, our school decided that we needed to memorize the names—with correct spellings—of every bone in the human body. My mom is a wonderful teacher and worked with me to help me learn the names. I got a perfect score on the test,5 but every other kid in my class got at most a couple right. Our teacher was livid. History repeats itself, because when my son was in fifth grade, his Spanish teacher decided that his class needed to memorize the capitals of all the Latin American countries. This was a stupid assignment, because internet, but my son has an exceptional memory, and so he was easily able to memorize them. He got a perfect score on the test and was one of very few kids in the grade to get more than a couple right. Again, his teacher was livid. An emphasis on the growth mindset allows us to persist in requiring kids to perform meaningless tasks like these, when we would be better off asking ourselves whether these requirements even make sense—and then we might stop forcing kids to pass Algebra 2 in order to earn a high school diploma, for example.

We can incentivize risk-taking instead of playing it safe. Go ahead—lecture kids about the growth mindset until the cows come home.

It won’t do any good, because kids can’t help noticing that all our incentives work in the opposite direction. When students keep their heads down and avoid making mistakes, they are doing so because we have made the consequences of those mistakes so dire. Kids are acting rationally when they take an easier class to ensure an A; they know that a single bad grade can keep them out of selective colleges, and that without a degree from a respected college, they will have a harder time finding a job with good pay and benefits in our insanely competitive job market.

If we want to encourage the growth mindset—and also make life better for our kids—we ought to allow students to take difficult classes pass-fail. Colleges should give more weight in admissions to students who have opted for the most challenging classes, even if they get lower grades than students who took easier classes. Top graduate and professional schools and corporate recruiters ought to consider applications from people who earn undergraduate degrees from a far wider range of universities than they currently do. And all employers ought to be open to candidates who have strayed from the straight and narrow and taken a winding path through life. The school of hard knocks can offer an excellent education too.

Finally, we can help kids discover their talents and pursue their interests. Sometimes what looks like a fixed mindset is actually a humble and realistic awareness of our own limitations. In my case, I knew that without a good teacher, I was never going to be able to solve those logic problem sets. The good news is that we all have plenty of gumption when the task is something we care about. To redeem myself for my failure in that logic class, I’ll just note that the summit hike I mentioned last week required me to ascend 1000 vertical meters (3280 feet) over 8 kilometers (5 miles). That may not be a challenge for my fitter readers, but for me it was at the edge of what I could do. Nevertheless she persisted, and I am proud to report that I have now added my thirty-second summit to my list.

A new school year is underway. Of course it doesn’t hurt for parents and teachers to remind kids that obstacles are a part of life, and that it’s important to persevere. But maybe we ought to shift our emphasis away from telling kids that every challenge must be overcome, and toward helping kids discover which challenges are worth the effort. It is unreasonable to expect every student to be a gung-ho go-getter at everything. Besides, some of us are late bloomers who need time to discover our vocation. As Milton, himself possessed of a great talent that flowered later in life, put it, “They also serve who only stand and wait.” Let’s honor that too.

How about you, readers? Do you have a growth mindset, or are you, like me, kind of a quitter? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

I’ll close with some inspiration—a remarkable display of growth mindset I saw back in high school, when I was the accompanist for my friend Jana in a statewide voice contest. Jana, who even as a young teen had a stunning coloratura soprano voice, had an excellent shot to win. But on contest day, she discovered that she was disqualified on a technicality. (She was supposed to bring two copies of her music, but because it was her first year at the contest, she didn’t know that and had only brought one copy.) Most of us would have argued with the judges or given up and stalked out of the room (or rushed out in tears), disappointed and upset, or angry and resentful. But Jana, undaunted, asked if she could perform her aria anyway—and she nailed it. Below is the aria Jana sang, at age fifteen. She may have been disqualified from getting a prize, but she was a winner nonetheless.

Jana went on to sing with Prince on several recordings, and she has toured the world as a backup singer for Stevie Nicks and Don Henley, among other artists. Of course her extraordinary talent played a role in her success, but so too did her growth mindset—her refusal to give up, and her hard work and dedication throughout her life.6 As you’ll hear in the short video below, talent and persistence are a formidable combination!

The source for this study is lost to the sands of time. A quick Google search of “leadership study beanbags” yielded a bunch of articles claiming that tech bros enjoy sleeping in beanbag chairs and arguing that police shouldn’t shoot beanbags at people. (Not the same articles.) This is edifying, I suppose, but not what I was looking for. Ah well.

I wonder if the researchers missed a better explanation for the kids’ later success? The few children who chose to toss the bag from the edge of the classroom almost certainly did so because they were more coordinated and athletic than the other children. American culture strongly favors athletic ability, and children with athletic talent receive disproportionate social rewards. It could have been these kids’ athletic ability, and not their willingness to take on the beanbag challenge, that caused them to become respected school leaders.

These studies can make some wildly exaggerated claims for the power of growth-mindset trainings. One study claimed that growth-mindset training could help lead to peace in the Middle East because “Learning about Gerry Adams led to the Israeli and Palestinian children building a 59 percent higher spaghetti tower” (this quote is at 14:45).

When you’re a little kid, you think the world just looks that way. As one example, after I got glasses, I was amazed to discover that squirrels have skinny ratlike tails with long hair, instead of fat squishy tails covered in short fur.

I still remember them: cranium, hammer, anvil, stapes, mandible, clavicle, scapula, vertebrae, sternum, ribs, humerus, radius, ulna, carpal, metacarpal, phalanges, pelvis, femur, patella, tibia, fibula, tarsal, metatarsal, phalanges. Gee, I’m so glad my school made me memorize this when I was nine years old. Not.

"our levels of growth mindset are innate and vary tremendously from person to person." One of those things that is obviously true but not allowed to be said, "genetics," you know. Bad thought. But what a wonderful world (or better anyhow) if we could value people simply as human beings doing the best they can with whatever gifts they have instead of pretending everyone with enough hard work and right mind set can be A students and in the professional class. MLK admired the street cleaner who took pride in his clean streets. Oh, that we could be like that.

Mari, is your conclusion that the growth mindset is not correlated with success or that the growth mindset is ineffectively taught?