Trust the Science

An Invitation to Change Our Minds in Response to Evidence

Let’s begin with a fanciful thought experiment and a little quiz. It’s 2030, and we’re in the midst of another pandemic. Alphaville is in lockdown, people maintain social distance, and businesses allow working from home. Because Alphaville is in an RC Cola distribution zone, people there drink only RC Cola and not Coke or Pepsi. Bravotown, on the other hand, has not gone into lockdown, and people there are living normally. They drink Coke or Pepsi. When researchers look at infection rates in the two towns, they notice that Alphaville is doing slightly better than Bravotown. In addition, a story is making the rounds that two hairdressers went to work while they were sick and drank RC Cola while cutting people’s hair, and no one got infected.

Now for the quiz. Which of the following two propositions do you think is true?

RC Cola is effective in preventing the transmission of infection, and we should mandate that everyone drink RC Cola.

There is not enough information in this scenario to determine whether RC Cola by itself is effective, whether some unknown combination of interventions is effective, or whether Alphaville’s slight success is due to another factor entirely.

If you answered 2, you are correct!

Thinking Like Scientists about Mask Mandates

The evidence in favor of mask mandates is no stronger than the evidence for RC Cola in my thought experiment—it rests on anecdotes (e.g. those hairdressers) and on comparing communities with and without mask mandates. Most people agree that public policy shouldn’t be based on anecdotes. However, the comparisons are scientifically useless as well, because there are multiple differences between communities that mandated masks and those that didn’t, any one of which could have caused the slightly lower rates of infection in places with mandates. Communities with mask mandates also closed schools, allowed working from home, and imposed lockdowns. In addition, blue communities have healthier populations than red communities. Was it the masks, or was it the lower rates of obesity, diabetes, and other chronic conditions, as well as better access to health care, that made the difference in blue communities? To determine whether mask mandates are effective in stopping transmission, we can’t rely on anecdotes and observations. We need randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of mask mandates, in isolation from all other interventions.

And now that is what we have, thanks to the highly-respected Cochrane Library, which reviewed several RCTs on the effectiveness of masking. (Among the studies they reviewed was the one in Bangladesh that compared villages with and without masking. This study has received a lot of attention in the media and has been cited to justify mask mandates, but its conclusions fell apart when researchers reanalyzed the data.1) After reviewing seventy-eight studies, Cochrane found that “The pooled results of RCTs did not show a clear reduction in respiratory viral infection with the use of medical/surgical masks.” The Cochrane reviewers note that it is still possible that community masking may offer a small benefit. They conclude that “There is a need for large, well-designed RCTs addressing the effectiveness of many of these interventions in multiple settings and populations, as well as the impact of adherence on effectiveness.”

A brief digression about adherence: People who believe in mask mandates have been criticizing the Cochrane review because none of the studies it examined had perfect adherence. For example, there are some 3800 comments on Bret Stephens’s op-ed about Cochrane’s results in the New York Times, and all of the top-rated comments argue that if only everyone wore their masks properly all the time, then the masks would work. This is probably true. But we have had three years of overwhelming evidence that Americans are unwilling or unable to be perfectly obedient about masks. You go to war with the army you have, not the army you wish you had.

I have some questions for these commenters, and for anyone who still thinks we should mandate masks and just make everyone comply. How do they propose to accomplish this, when tens of millions of people have already shown they don’t want to wear masks at all, let alone perfectly and all the time? Put police everywhere? Insist that teachers waste instruction time on constantly bugging kids to fix their masks? Deputize citizens to inform on their neighbors? Install surveillance cameras in restaurants to ensure that diners replace their masks between bites and sips? And then punish the scofflaws? Bad as Covid is, I hope that we all agree that the amount of policing required to make the mandates work would be worse. Ok, glad I got that off my chest. Thus endeth the digression.

It is easy to stick with a favorite idea because it is seems logical or is espoused by our political tribe. As Gurwinder put it recently (in this short article),

we excel at guarding our beliefs from evidence that threatens them. . . . If a belief you hold can’t be falsified, then this is a sign that you’ve protected it from reality. As such, for each of your beliefs you should develop a clear idea of what would persuade you you’re wrong. If you can’t, your belief is immune to reason and you should be highly suspicious of it.

I would like to challenge readers to think like scientists, even when it comes to such entrenched beliefs as “mask mandates work.” Scientists test a hypothesis systematically, by isolating a single variable and comparing it against a control. If the test reveals that the hypothesis was incorrect, they revise their conclusions.

Further Evidence from Switzerland

As early as the fall of 2020 there was evidence from Switzerland that mask mandates were ineffective in stopping the spread of infection. This evidence was especially convincing because the Swiss complied with the mask mandates so meticulously as to satisfy even the most worried New York Times commenter. We did not have people getting into arguments about masks, or trying to sneak into places without them, or letting them rest below their chin or dangle off their ear; everyone just cooperated and wore them properly from day one. (The Swiss respect for rules is a wonder to behold.) But even when given their very best chance, masks didn’t seem to do much. Unfortunately, whenever I would mention the evidence I was seeing, people would ignore it, or try to explain it away, or even admonish me2 for daring to bring it up.

As I have written before, in the spring of 2020, Switzerland had the second-highest per capita rate of Covid infections in the world (behind only Italy). The health authorities closed schools and nonessential businesses for several weeks and encouraged people to socialize outdoors. By the end of May schools were again open, and many restaurants and bars were open for outdoor customers. The authorities didn’t require anyone to wear masks, and no one wore them. Nevertheless, the number of daily infections dropped to the single digits nationwide during the summer.

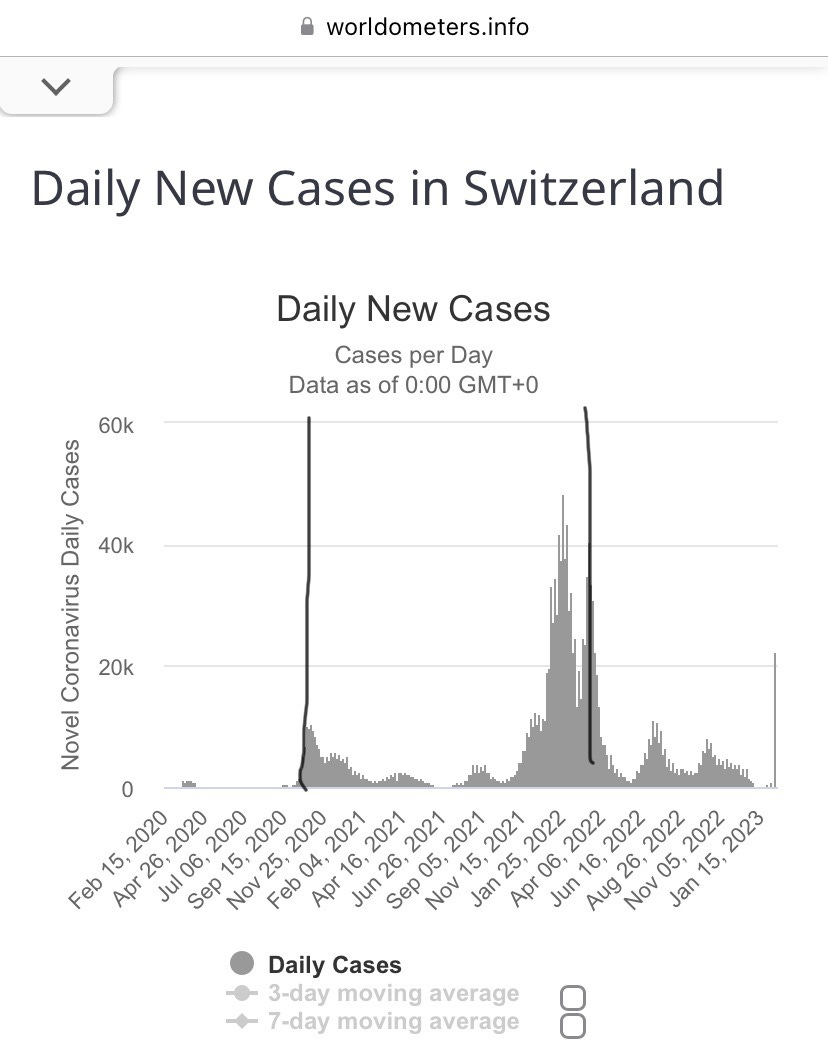

In August 2020, a couple of superspreader events (including, amusingly, a yodeling retreat) caused the infection rate to surge, and so the health authorities imposed a mask mandate. The mandate was lifted nationwide in February of 2022; from that point until today, the infection rate has dropped sharply.

We can’t tell from the graph how effective the mask mandate was in slowing transmission (or whether it was effective at all) because we don’t have a control group. But the graph does show that claims by health authorities and in the media that mask mandates would stop the pandemic in its tracks are unfounded.

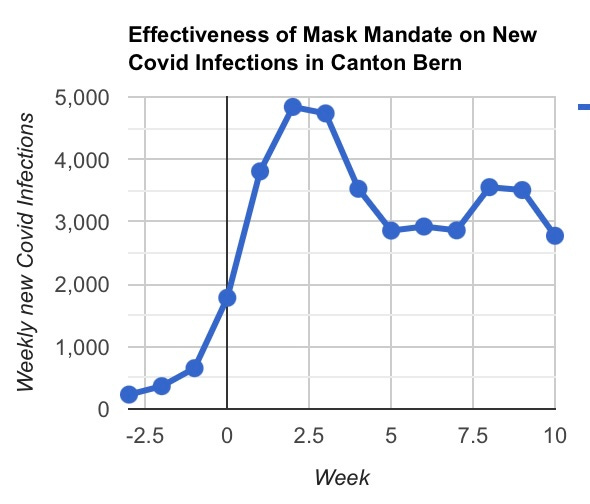

In the fall of 2020 I had an opportunity to observe a natural experiment in the canton of Bern, where I live. Bern imposed a mask mandate for all indoor spaces beginning on October 17, 2020. Before that date, no one wore masks, and after that date everyone did. In addition, no other pandemic interventions were being imposed at the same time, so I was able to observe the effectiveness of a mask mandate in isolation from all other factors. Finally, the health authorities published the number of new infections each day, so it was easy to collect data. (The government no longer tracks infections, but here is where I obtained the data.) Here are the results:

If the mask mandate were as effective as claimed, we would expect the line to start dropping somewhere between weeks 0 and 2.5 and to remain low for the duration of the mandate. Since there is no control group, we don’t know whether or to what extent the mandate made the infection rate better (or worse!). But the graph does show that even in a population that masked assiduously, the infection rate continued to shoot up and remained high. The masks might still have been somewhat helpful, but if they were, it was pretty weak sauce.

Costs and Benefits of Interventions

When authorities contemplate forcing an intervention on an entire population, they ought to be very sure that that intervention is beneficial, especially if it is imposes costs. When an intervention is obviously beneficial, people recognize that and are willing to shoulder the burden. For example, during the Blitz, Londoners cooperated in keeping their lights out and using blackout curtains to protect themselves and their neighbors from German bombs. Or think of how people gratefully lined up for the polio vaccine when it became available.

The evidence suggests that mask mandates offer little benefit. What about the costs? Many of my compatriots on the left seem to think that there are no costs to mask mandates so we might as well impose them just in case. Articles about Covid during the past three years in the mainstream media are always followed by scores of baffled, irritated commenters who complain, “I just don’t understand why people don’t want to wear masks! They are not a big deal! Stop being selfish and put on the damn mask!” Comments like these remind me of James Stewart in that scene in Vertigo when he urges Kim Novak to dress in Madeleine’s clothes and bleach her hair because “It can’t make that much difference to you!”

The fact is, it does make a difference to us. Most people who aren’t Orville Peck hate masks, otherwise we would be wearing them even without being told to, even right now, because why not? If masks are no big deal, why did most people take them off the moment it was allowed? I experienced this phenomenon myself. A year ago, my husband and I traveled to Venice on the train. Switzerland had no mask mandate, but Italy still did. Everyone on the train waited until the moment the train crossed the border into Italy to put on the masks, and on the way back, the moment we crossed the border into Switzerland off they came again.

Masks itch, and after a few hours they smell bad. They are soggy and hot in summer. They cause acne and rashes. They get painful behind our ears. They fog up our glasses and obstruct our peripheral vision. There is good reason to suspect that they hamper children’s language and social development.3 Masks impede communication because they muffle consonants and hide our facial expressions. They put up a physical barrier against the friendly encounters with strangers that brighten our days. They provoke unnecessary conflict. Mandates reinforce class hierarchies, because service workers, unlike white-collar workers in their home offices, must wear masks in order to keep their jobs. Discarded masks litter the streets and pollute the environment. If the masks provided a proven, significant benefit, it would be worth mandating them for everyone in spite of these costs. But in the absence of such evidence, we should acknowledge that the costs of mandates outweigh the benefits, and that therefore mandates are not warranted.

The Evidence Suggests That Masks Are Like Helmets

Instead of viewing masks as a panacea that must be foisted on everyone all the time, we should think of them like helmets—a safety measure that is necessary in some situations and for some people, but that is otherwise optional. It is a shame that masks became so politicized, because while the evidence suggests that mandates don’t work, it does support masking for individuals who are at heightened risk from Covid. In future pandemics, health officials ought to follow the evidence, speak honestly to the American people, and say, “If you are worried for any reason about catching this disease, you can protect yourself by properly wearing a high-quality mask”—and then leave it at that.

As for this pandemic, when for almost a year now 95 percent of the US population has been protected from severe Covid through vaccination and/or previous infection, mask mandates are reminiscent of that joke from Arrested Development4 about Tobias Fünke’s mom, who made him wear a helmet to play chess. Let’s be more sensible than Tobias Fünke’s mom, let’s trust the science, and let’s support evidence-based policies—on mask mandates, and indeed on all issues.

This post has taken a deep dive into the evidence against mask mandates because of the new results from the Cochrane review and because—as you have no doubt sussed out—I hate masks. If you don’t hate masks, it might be a challenge to change your mind in response to this evidence. I sympathize, because I have changed my mind about something I badly wanted to be true, and it was a bummer. As an enthusiastic drinker of beer, whisky, and wine, I wished so much that those studies showing the health benefits of moderate drinking were valid. But when I learned that the studies had been funded by the liquor industry and didn’t control for socioeconomic or health status, I had to revise my assumptions and admit that alcohol is not a health food. Tough as it may be, we all need to be doing this kind of thing more often. It is unpleasant and difficult to discard cherished beliefs when we get new evidence, but if we want to make smart choices in our own lives, as well as to advocate for wise public policies, we must be willing to change our minds.

So what do you think, readers? How can we encourage people to think more like scientists? And have you ever changed your mind about something when you got more information? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Orville Peck was born in South Africa and lives in Canada. And yet he sings like the reincarnation of Johnny Cash. This song showcases his beautiful voice:

In honor of the tiny northern Minnesota towns of my childhood vacations, where RC Cola was our only choice because of distribution contracts, I present “RC Cola and a Moon Pie,” by NRBQ:

In the words of the researchers performing the reanalysis, “we find a large, statistically significant imbalance in the size of the treatment and control arms evincing substantial post-randomization ascertainment bias by unblinded staff.” In addition, while the published paper didn’t include raw numbers, the reanalysis obtained them and found that “the primary outcome differed by a total of just 20 cases between the treatment and control arms: In a study population of over 300,000 individuals, there were 1106 symptomatic seropositives in control and 1086 in treatment.” Finally, “No placebo intervention was implemented in control villages.”

For example, a Taiwanese woman I know messaged me to say that in Taiwan, everyone wore masks, and they had almost no infections. True, but it wasn’t because of the masks: Taiwan closed its border before infection could enter the country in the first place.

Another friend touted Czechia’s strict mask policy, which she credited for the low infection rate there. Again, though, Czechia closed its border at the start of the pandemic, before any infected people could enter the country. In spite of Czechia’s extremely strict indoor and outdoor mask mandate, once the borders reopened, infections surged, and Czechia became one of the worst countries in the world for per capita infections and deaths.

I think we should test this hypothesis too. If we want to make smart decisions about what to do in future pandemics, we need to know whether children were harmed by mask mandates, or whether they were basically ok. Scientists should perform a longitudinal, well-designed study that compares the educational and social development of children who spent the first few years of life under a mask mandate with those who didn’t (matching children for family income and other demographic factors).

Or at least I think this is where I saw the joke about the chess helmet. When I googled “chess helmet” to check, all I got was ads for helmets with chess patterns on them.

Great post! I too hate masks and especially hate their effect on communication and socialization. Every year we get 36 new 19-y.o. students in our design studio-based degree program, and it's a very interactive program. A very strong and enduring sense of community always develops among the class, but the class of Fall 2020 is an exception. They just never really have "clicked" as a group. Another weird thing: when I see those guys around the building (now maskless of course), I often don't recognize them, because I spent the first two semesters (Fall 2020 and Spring 2021) never seeing their faces.

Something I keep noticing: a great many colleagues here at the university seem to have been very, very attached to the idea of mask mandates and also the idea of remote teaching/meeting as a reasonable alternative to in-person interaction at the university. Not sure what's going on here. It seems like some amalgam of excessive "safetyism" (all precautions are unquestionably a good thing; not gonna even talk about downsides) and rationalization (from the comfort of my home office, as opposed to my office in that big building several miles away, I insist that remote teaching is working just fine).

It always seemed to me that masks were probably helpful for protection from coughing or sneezing people. I'm guessing this is why transmission of other communicable diseases like seasonal flu dropped off in the masky era. But even at the outset, I thought mask mandates outdoors on campus were silly. These were of course, not opinions based on science, but rather on intuition.

But I'm just sayin': my intuition works pretty well sometimes. Remote teaching was a massive fail. This seemed blastingly obvious to me from the start, for so many reasons, not the least of which being the total breakdown of peer-learning (design studios heavily rely on this as pedagogy). But for the entirety of 2021—both semesters—in-person teaching was optional, and the majority of instructors stayed home. I pretty much had the Design building to myself (and the parking lot, which was nice, haha!).

Maybe I'm a cynic, but I suspect there were very powerful motivational undercurrents around here during the COVID epoch. People are complicated, I always say, so it is a mistake to write them off for some presumed devious motivation. People make choices and take stances for a whole array of reasons. In any case I see circumstantial evidence that remote teaching was very much grounded in convenience (at great unacknowledged cost for teaching and learning), and that mask-wearing eventually became at least partly a sort of uniform or "signifier" of allegiance, a political act and a desire to assert control.

We are a "University of Science and Technology", but "science" had kind of gone into hiding.

One way to get people to think more like scientists would be to encourage them to be very skeptical of medical and science reporting, even about something that seems so science-y, so cut and dried, and so respectable on the surface as a Cochrane review.

I’ve been reading faulty health and medical reporting for too many decades to think health decisions should be made by each of us based on what we read in the media.

I’ll just hit a couple little points because no one wants to hear my whole spiel:

I object to the media’s takeaway message from the Cochrane review that “masks don’t work.”

Maybe it’s true that “masks don’t work” if you wear them incorrectly or wear them in situations where you don’t need them (eg, the beach; or a meeting room with an open window; or you expect kindergartners to wear them all day long).

You make a good point about “the army you have” Mari, and also: The army would not be hard to train to be more effective with good public health messaging. I cannot emphasize this enough: This is such a solvable problem. It would not be hard to teach people:

1. What kind of masks work?

N95 or KN95

2. How are they properly worn?

a. Choose a size that is fits close to your face.

b. Press the metal adjustable band so it fits closely around your nose.

c. If the mask moves in and out a bit with your breathing, that’s a good enough fit (and will probably avoid glasses fog).

3. When should I wear one, in a way that makes a difference to myself and the community?

This is a judgment call, but in general for a healthy person, the answer is “crowded indoor poorly ventilated spaces where you’ll be for a long time.“ Examples:

subway at rush hour

crowded lecture call

standing-room-only jury selection room

That’s about ALL people need to know or understand. It would be so easy to teach people what’s effective.

Maybe in fact “masks are very effective” if you choose the right time, place, mask, and method of wearing them, which is as simple as I just laid out. And not just great for the wearer; great for the wider community (as epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina pointed out last week in her substack post about the Cochrane review):

“even if masks only reduce the risk of transmission for each individual by a small fraction, when a community masks, those small effects compound exponentially across a population, making a big dent in cases. Just like compounding interest—a small change in the percentage makes a big difference down the road.”

https://open.substack.com/pub/yourlocalepidemiologist/p/do-masks-work?r=r6z4&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post

To me it’s a shame (more than a shame) when the information is presented through the lens of a media who say things like “Look! Masks don’t work!”

Is anything that simple?

Why did health care workers stop dying when they figured out the right PPE to wear in covid units (before the vaccines)?

And as I pointed out on a different substack last night, asking whether masks work makes as much sense as asking whether vitamins work: which vitamins? in what form? taken when? how much? for how long? for what purpose?

This Cochrane review jumbled too many things together with predictable results. If you jumbled together all the research on “whether vitamins work,” you’d come up with a big, correct “no,” but you’d also miss — in that same jumble— the fact that even if most vitamins truly don’t live up to their claims, vitamin K shots do prevent bleeding conditions in newborns.

The answer to sweeping questions (do masks work? do vitamins work?) will almost always be no. The answer to specific questions (do well-fitted N95s in close quarters prevent covid infection? do vitamin K shots prevent bleeding in newborns?) is often more interesting.

And while we’re waiting for better treatments and preventatives for covid, which I believe are coming, wearing “well-fitted N95s in close quarters” in targeted commonsense situations is something we can do not just for ourselves but others.