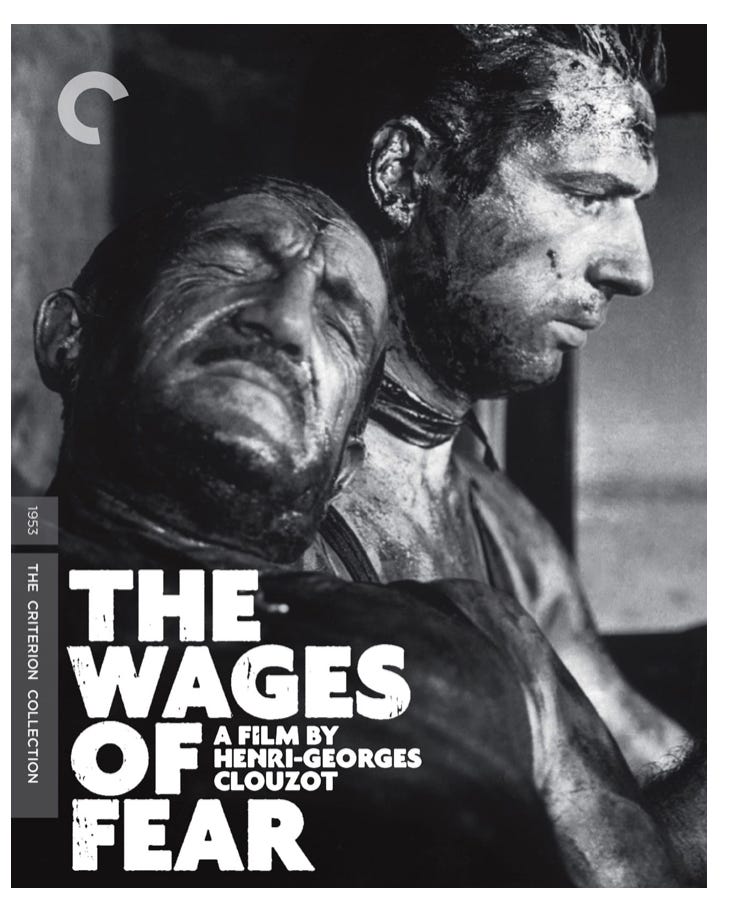

The Wages of Fear is a French masterpiece starring Yves Montand as Mario, one of four desperately poor men who are hired—at a temptingly high wage—to drive two truckloads of nitroglycerine across bumpy dirt roads. The tension is almost unbearable, because the slightest jolt will blow the men up. The critic Pauline Kael has called the film “a parable of man’s position in the modern world.” I will return to the film at the end of this essay, and there will be spoilers, so if you haven’t seen the film, please consider watching it now.

Wasn’t that a gripping and powerful film? And now on to the essay.

Balancing Risks and Benefits in Daily Life

For my whole life, I have blithely ignored warnings that eating raw cookie dough can give you salmonella. Whenever I am in proximity to raw cookie dough, I plunge an eager finger in and snitch a hefty scoop. Delicious! Guess what? I did indeed get salmonella from raw cookie dough once, and I am here to tell you that a lifetime of eating raw cookie dough has been totally worth that one bout of salmonella. So. Worth. It.

We all resent having to take off our shoes at TSA checkpoints and suspect that it is mere security theater—especially since people can buy their way out of the hassle with a business-class ticket, elite status, or Global Entry. I would wager that most of us would be willing to face the infinitesimal risk of another shoe bomber for the benefit of faster (and less stinky) security lines.1

There is an excellent reason that obstetricians usually offer amniocentesis only to pregnant women who are 35 or older, and not to younger pregnant women: Amnio carries its own risks, but beginning at age 35, the likelihood that amnio will reveal a problem is greater than the risk that it will cause a problem.

My favorite hobby, hiking in the mountains, can take me on some sketchy, high-altitude trails, where I need to sidle along a narrow track with a sheer drop-off on one side (or both!), where I need to scramble over boulders, or where I need to watch my footing on a scree-covered slope. However, I find the benefits of hiking to my mental and physical health to be well worth the slight risks.

I tricked you. This has been a Covid post all along. Whenever we make a decision, whether it’s to eat the cookie dough or to set out on that mountain trail, we must consider the risks and benefits of our actions. But during crises like the pandemic, fear can overwhelm our rational ability to correctly balance the risks and benefits of various interventions. In the rest of this essay, I will discuss three strategies to help us make decisions based on reason rather than on fear. Next week, I will discuss Switzerland’s exemplary performance during the pandemic.

Finding Balance, Literally and Figuratively

For an avid hiker, I am actually kind of a klutz—which adds to the risk of hiking, obviously. To mitigate the risk, I select trails that are at my level (which for me is no higher than T3), and I have equipped myself with good shoes and poles and availed myself of my friend Peter’s kind offer to teach me basic tai chi over Zoom2 to help improve my balance. (And should something go wrong, I hold helicopter-rescue insurance.)

Similarly, during the pandemic and in any crisis, we can equip ourselves to maximize our personal safety. We can get vaccinated and boosted, and if we get sick and need it, we can take Paxlovid. If we’re in a high-risk group, we can wear an N95 mask and practice social distancing. If we’re immunocompromised, we can ask our doctors to prescribe Evusheld. And we can allow ourselves to be reassured by the research demonstrating that these measures are highly effective protections.

But we also ought to realize that not everyone faces the same risks, and that safety measures that are beneficial for one group may be harmful to others. For example, nationwide, Head Start children are still required to wear masks. These children face the least risk from the virus—and the most risk to their language and social development from the masks. It makes no sense to force these children to follow a mandate we don’t impose on anyone else. We are not all the same, and we would be better off if we tailored our safety measures appropriately—and took masks off little children.

Fear Drives Engagement

I got Covid last month. It was like having a mild cold for a few days, except that I also lost my sense of smell. Because smelling things is one of my top-five ways of perceiving the world, I was worried, so I started Googling—and was not comforted by what I read. I had forgotten about my husband’s rule, If the Internet Says Something Crazy, Ask a Person Who Knows Something. Luckily for me, a couple of friends who work in healthcare messaged me to let me know that olfactory nerves, uniquely, can regenerate, and that I should practice smelling things to remind them of their job. And it worked! (Cardamom proved to be especially helpful.) After a couple of days, my sense of smell came back just fine.

I found myself wondering why this crucial piece of information—that olfactory nerves regenerate—had been omitted from articles on the topic. My experience reminded me of a perverse incentive that operates in the media: Frightening and controversial stories get more clicks than balanced, nuanced ones. Journalists face a dilemma. They can choose to escalate fear (and drive engagement), or they can communicate the true complexity of the issues (and lose readers). Many of them unfortunately choose the former option. But, for our part, we should consume media with a critical eye and be skeptical of the most extreme claims.

Let’s practice this skepticism on the topic of long Covid, the fear of which is driving people to continue to isolate themselves and to call for extending such restrictions as mask mandates and school closures. The CDC claims that as many as 20 percent of all American adults suffer from long Covid, a statistic that the media repeats unquestioningly. This is a terrifying statistic. But let’s do a quick reality check from our own lives. Think about the hundreds of people we know—friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, online friends, and so on. How many of them have been permanently debilitated by Covid? Maybe we do know a person or two in this tough situation, but I doubt it is 20 percent of everyone we know.

Next, we can examine how the study was done. In the case of the CDC study, if we read the fine print,3 we discover that most of us are probably not in as much danger as the anxious reporting in the media suggests. First, the CDC obtained its data by correlating the symptoms and Covid antibody test results of people seeking treatment for a variety of health problems. Because the data came from people who were already seeking medical treatment, the study population is probably sicker than (and thus not representative of) the general population. In addition, the study didn’t take into account the following extremely relevant criteria:

Whether subjects had been vaccinated and/or took Paxlovid, and

Whether subjects had contracted one of the earlier, more severe, variants of Covid or one of the current, milder, Omicron variants.

If we are vaccinated, basically healthy, and/or contract Covid in its current milder form, the CDC study may well not pertain to us.

We can also clarify the terms being used. People who fear long Covid are thinking about a catastrophic illness that will permanently ruin their lives. The CDC’s list of symptoms of long Covid includes many that are indeed disabling—for example extreme fatigue, cognitive damage, and breathing and heart problems.4 However, other symptoms—for example dizziness, anxiety, insomnia, rashes, stomach pain, and headaches—are less serious and could arise from any number of causes, including stress caused by the Covid restrictions themselves.

Moreover, the CDC counts symptoms as long Covid if they persist for more than a month. While it is a bummer to suffer from any symptom for more than a few weeks, most of us who fear long Covid aren’t worried about short-term dizziness, rashes, and the like. How many of the CDC’s estimated 20 percent of American adults are afflicted by what people would consider true long Covid, versus how many are experiencing unpleasant but minor problems for a few weeks? How many of them are suffering from problems arising from some other cause that has nothing to do with Covid? We don’t know. The 20 percent figure amalgamates a spectrum of experiences, from minor to deadly, into a single, frightening, statistic.

Finally, we can check up on frightening stories by looking at other sources of information. If long Covid were truly destroying so many lives and rendering such a large percentage of the population unable to work, we would expect to see a surge in applications for disability insurance after 2020. Instead, online applications for SSDI remained flat from 2020–22, and there has been no increase in applications even after local Social Security offices reopened at the beginning of April. This shouldn’t surprise us; other postviral illnesses (for example chronic fatigue syndrome, which is likely caused by the Epstein-Barr virus) are quite rare.5 There is no reason to suspect that long Covid should be any different.

The Blind Mice and the Elephant

You probably know this story. Seven blind mice encounter a large obstacle and wonder what it could be. Each mouse examines one part and makes assumptions about the object based on their limited perspective—that the obstacle is, variously, a pillar, a snake, a fan, and so on. Only when the last mouse examines the entire elephant do the mice reach a true understanding of what they should do about the obstacle (which, in Ed Young’s delightful version of the story, is to take a ride on the elephant).

During the pandemic, the mantra has been “Trust the experts,” and I agree with this, but with the proviso that there is more than one field in which to be an expert. Of course epidemiologists have relevant knowledge and insights to share, but so too do experts in education, child (and adult) psychology, addiction, crime, and the economy. All of these experts could have pointed us to the risks and benefits of various interventions during the pandemic. But we only listened to one mouse. As Josh Barro has pointed out,

experts aren’t supposed to make policy; they’re supposed to advise political leaders on policy, so political leaders can combine expertise with value judgments to make decisions in the interest of the public.

The ravages of Covid have not been confined to the disease itself. It is true that the virus has caused a heartbreaking loss of life. But pandemic restrictions like closing schools, parks, and businesses and encouraging people to isolate themselves from friends and family have damaged the educational prospects of schoolchildren, the physical and mental health of too many Americans, and the economic circumstances of nearly everyone. At the beginning of the pandemic, especially in places like New York City, Covid was by far the most salient risk; it made sense to listen to epidemiologists and impose restrictions in order to prevent hospitals from being overwhelmed, and to save lives. But once vaccines and treatments became available, experts in education, mental health, and the economy could have helped us decide which restrictions carried their own risks that outweighed their benefits.

The Wages of Fear ends with a terrible irony. Two of the men are blown up and another is run over; only Mario survives. He pockets his wages and stops at a bar to celebrate. Driving home drunk, he crashes his car and dies.

We humans have a glitch in our fear response: We tend to fear rare, spectacular events but to forget about quotidian threats. Mario feared the nitroglycerine but forgot about the danger of drunk driving. And we were so frightened by Covid that we neglected to take into account what prolonged isolation and school and business closures would do to our mental, physical, and economic health. In the future, if we want to make wise policy decisions that balance the risks and benefits of interventions, we must reject the wages of fear.

Well, readers, this was a controversial essay, and I thank you for keeping an open mind and sticking with me. I’d love to know what you think. Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

The ability to bake apparently skips a generation, because my mom and daughter, unlike me, are ace bakers. My mom reports that the best chocolate-chip cookie recipe among the many she has tried is the Nestlé Toll House recipe—the one on the chocolate-chip cookie bag. Here are some of my mom’s and daughter’s tips for making an already terrific recipe even better:

Don’t lie to yourself about the kind of cookies you like. If you like crispy cookies, bake them a little longer, even if other people like chewy cookies.

Use a high-quality unsalted butter like Kerry Gold (available at Trader Joe’s, Target, and Whole Foods).

Whip the butter and sugar way longer than you think you need to.

Sprinkle a tiny bit of salt over each cookie to make the chocolate flavor pop.

Chill the batter before baking and use a 1-1/2” ice-cream scoop to apportion the cookies evenly.

Freeze the scooped batter in a ziploc bag for later. When you’re ready to bake, put the frozen batter on the sheet and straight into the oven.

For any doubters out there, no European country requires passengers to remove shoes in the security line. How many shoe bombings have there been in Europe, ever? Zero.

Peter offers these lessons both in person and over Zoom. You can contact him here. I highly recommend his lessons to anyone who wants to improve their balance, strength, and equanimity in times of stress.

The CDC report does mention five potential limitations to its conclusions near the end, but I have not seen these limitations mentioned in the many articles I’ve read about long Covid.

To address the problem of postviral illnesses, the sociologist Zeynep Tufekci, in the New York Times, has called for “a National Institute for Postviral Conditions, similar to the National Cancer Institute, to oversee and integrate research.” Tufekci has been prescient throughout the pandemic; she was among the first to argue that the virus was airborne rather than spread by fomites, and she recommended rapid-testing and ventilation as effective and easily-tolerated safety measures long before anyone else had acknowledged their importance. I think we should listen to her on the important issue of long Covid too.

While it is estimated that about 90 percent of Americans have been infected by the Epstein-Barr virus, chronic fatigue syndrome afflicts only about .235 percent of Americans.

Smell being in your top five favorite ways to perceive the world made me laugh out loud! I love when people sneak in little bits like this.

"experts aren’t supposed to make policy; they’re supposed to advise political leaders on policy, so political leaders can combine expertise with value judgments to make decisions in the interest of the public."

I think there's an even bigger problem here: people don't know what they're experts in. I touched on this in my bullshit jobs article, but one company I was at had a very high ranking executive get fired and everything ran more smoothly after his firing. A lot of workers can attest to something similar. I think this stems from the following fact: a Chief X Officer or Vice President of X may not know much about X. What they really know is how to get promoted in a corporation. That's their actual expertise.

I think the same might be true of epidemiologists and other academics. You might think someone with a PhD in epidemiology is good at epidemiology, but their actual expertise might be getting citations and popularity within academia. I think Tyler Cowen, an economist who doesn't even pretend to know about epidemiology, offered a lot more insight into the pandemic (and more accurate predictions) than the alleged experts. Funny enough, Cowen is an economist, and I disagree with him on a lot of economics. I think his expertise is probably his general ability to analyze ideas rather than economics.

I also think the lack of actual knowledge among medical academics is especially obvious in at least one other hot-button political issue, but that's a topic for another day.