They Also Serve Who Only Stand and Wait

An Appreciation of Penelope Fitzgerald

Now that the school year is underway, many of us have extra time for reading. Might I make a humble suggestion? Try a novel—any novel—by Penelope Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald wrote her moving, wry, well-plotted stories in clean, spare prose. As a bonus for the time-strapped, most of her novels are short—under two hundred pages.

For much of her career Fitzgerald was misunderestimated. This may be because, as her biographer, Hermione Lee, puts it,1

She is drawn to failures and lost causes, and her novels deal with people in a muddle, hopeless cases, outsiders; what she called “exterminatees.” These include children, and women, whose lives she wrote about with deep sympathy. … [S]he is alert to cruelty, tyranny, or unfairness. …

She was not glamorous or self-advertising. On the contrary, she was evasive and reserved, and gave a misleading impression in public of a mild, absent-minded old lady. She wrote in a quiet voice, slipping unpredictably between comedy and darkness. For all these reasons, she did not become a popular writer.

My mission in this post is simple: To persuade you to give this unglamorous, reserved, but quietly brilliant writer a try.

A Lifetime of Love and Grief

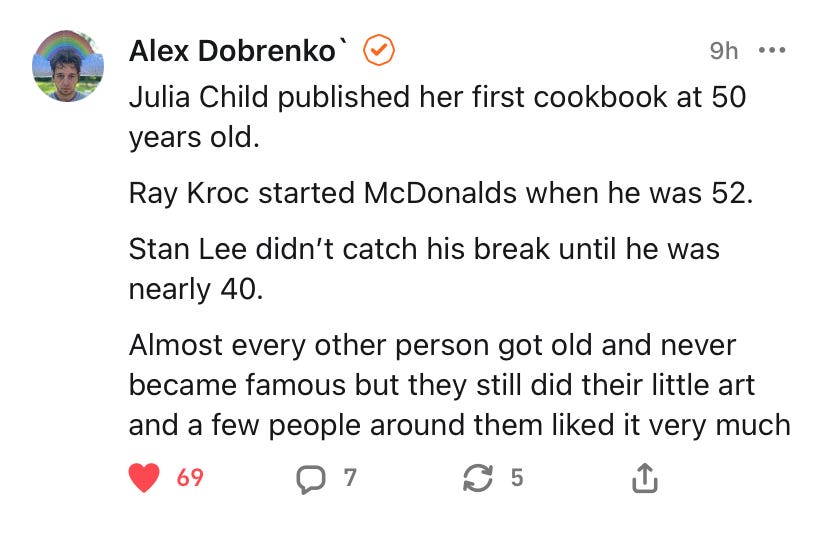

Fitzgerald was sixty when she published her first novel, The Golden Child, which she had written to distract her husband from the pain of his terminal illness. Most observers view Fitzgerald’s subsequent career as a late-in-life flowering of an astonishing talent, and as an inspiration for aspiring artists of a certain age.

But as we learn from Lee’s biography, this understanding of Fitzgerald’s career is a bit of a myth. Fitzgerald had been preparing her whole life to be a great novelist. She grew up in a family of quirky intellectuals; one of her uncles, Dilly, was a mathematical genius who served at Bletchley Park and helped to crack the Enigma code. Fitzgerald was a star at Oxford and didn’t even have to sit her final exams. Instead, when she walked into the examination room, her professors applauded her. Before she became a novelist, she was a writer, first at the BBC and then for a literary magazine whose authors also included Orwell, Eliot, and Waugh. Fitzgerald’s personal life gave her plenty of harrowing material for her novels. She married a charming aristocrat who was unfortunately also an alcoholic and a criminal. As a young mother she struggled with genteel poverty that devolved into homelessness.

Until her final years, Fitzgerald was an underdog in the highbrow literary world. When she won the Booker Prize for Offshore in 1979, critics were outraged that the award hadn’t gone to V. S. Naipaul, and the press openly insulted her. She appeared on a panel show after the award, and the panelists didn’t even speak to her but simply read out the tributes to Naipaul they had already written. When an interviewer asked Fitzgerald what she would do with the prize money, she joked, “Buy an iron.” The interviewer, making assumptions about such a mild-mannered older woman, thought she was serious! As a mild-mannered older woman myself, I can’t help loving this story.

Autobiography and August Institutions

Fitzgerald based her first five novels on her own life and on her experiences at some famous British institutions.

The Golden Child (1977). A museum is hosting a major exhibition of a King Tut–like archeological discovery. And then people start dying. Is it the Curse of the Golden Child, or is something else going on? Sir William (whom I picture as Michael Caine) had been a swashbuckling adventurer when he discovered the treasure decades ago. Now he sits in his attic office fretting about the hours-long lines to which the museum-goers are being subjected. The novel’s villain, Hawthorne-Mannering (whom I picture as Ben Wishaw), is “an exceedingly thin, well-dressed, disquieting person, pale, with movements full of graceful suffering, like the mermaid who was doomed to walk upon knives.”

And our hero is Waring Smith, oppressed by his mortgage, badgered by his querulous wife, repeatedly reminded that he “was not, or should not have been, of any kind of importance,” and buffeted about by winds of fate—all the way to Moscow and an encounter with a shadowy figure at the Kremlin. Fitzgerald honors the solidarity of “unimportant” people waiting patiently—whether in life or just in line at a museum—for something to happen.

Offshore (1979) is the story of a found family of artists, dreamers, and misfits who live on decrepit houseboats on the Thames. After her husband abandons her, Nenna takes her two young daughters to live on the Grace, a tiny, temperamental houseboat that constantly threatens to capsize. The denizens of this tiny community care for each other (and enjoy the occasional assignation). Fitzgerald and her children lived on one such houseboat, and she based her characters on herself and her unconventional neighbors: “A certain failure, distressing to themselves, to be like other people, caused them to sink back, with so much else that drifted or was washed up, into the mud moorings of the great tideway.”

A mood of comic melancholy pervades the book, and yet Fitzgerald refuses to let her fictional world be as bleak as reality. Speaking of a character based on a friend who died by suicide, Fitzgerald wrote, “I couldn’t bear to let him kill himself. That would have meant that he had failed in life, whereas, really, his kindness made him the very symbol of success in my eyes.” At the same time, Nenna’s daughters’ understanding of kindness is more cynical. Tilda proposes they cadge a ride from a friend, Martha protests that that would be taking advantage of his kindness, and Tilda responds,

“It’s his own fault if he’s kind. It’s not the kind who inherit the earth, it’s the poor, the humble, and the meek.”

“What do you think happens to the kind, then?”

“They get kicked in the teeth.”

Human Voices (1980) is a bagatelle of only 125 pages, set at another august British institution, the BBC, during the Blitz. The novel’s unlikely hero is the sound engineer, Sam Brooks, who is rather daft; he goes on a junket to record background sounds for the broadcasts and returns with seven hours’ worth of recordings of a creaky door—and nothing else.

Maybe your favorite character will be Annie, whose love for Sam is an affliction: “Hers must have been the last generation to fall in love without hope in such an unproductive way. After the war the species no longer found it biologically useful, and indeed it was not useful to Annie.” (Annie is based on Fitzgerald herself, who did indeed fall hopelessly in love with a top BBC man.)

Personally, I have a soft spot for Willie, a teenager who dreams up wildly unlikely plans for a better world:

“It’s generally accepted already that if everyone were to eat one day and have nothing at all on the next we could ensure world plenty. But I’d like to see more than that. Those who serve and those who are served would also change places in strict rotation, so that to-morrow evening, for example, you in your turn would be waited upon.”

At which point Willie’s pragmatic sister, Vi, steps in to bring Willie back to earth: “‘I shouldn’t like to be here when you’re doing the serving, Willie. There’d be long delays all round.’”

At Freddie’s (1982). The titular character runs a children’s theater school in London and is endowed with such a force of will that her name has become a verb. To be “Freddied” might be, say, to come to her complaining that one of her students has played a prank that put two of your employees in the hospital, only to discover that you have somehow promised to donate your spare carpets and furniture to her. The novel’s hero, Pierce, is so hapless and hopeless that you want to give him a hug—or a good shaking. On his first date with his crush, Hannah, he takes her back to his place and … reads aloud to her from the newspaper. When she protests, he says, defensively, that he has combed through the whole paper to find articles that will be particularly interesting to her.

After they spend an underwhelming night together, Pierce creeps out at 4am to race home and tell his extended family that he is about to be married and needs a plot of land for his new bride—whom he has neglected to inform of the matter.

In the midst of the comedy we have a hint of tragedy, though. While the other characters are out and about, the school’s most gifted pupil, Jonathan, practices stage falls from a wall above the school’s brick courtyard in a scene that recalls Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts”:

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just

walking dully along;

. . .

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster;

. . .

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky

Late Masterpieces

Fitzgerald’s last four novels are now acknowledged to be masterpieces. This post is already running long,2 so let me whoosh through them.

I am not a fan of Innocence (1986), the love story of Chiara, a young aristocrat, and an older doctor who, inconveniently, happens to be a Communist. I began to lose patience with their passionate outbursts and inability to get over their differences. But undoubtedly this is my failing, and not the book’s.

On the other hand, I love The Beginning of Spring (1988), which I rhapsodized about a couple of years ago:

Set in Moscow in 1913, … this novel tells the story of Frank, an Englishman whose wife abruptly leaves him and his three young children. He sets about rebuilding his life with mixed success. Interspersed among the events in the main story are hilarious set pieces—for example, a student shoots at Frank, and for some inscrutable reason the Russian authorities decide that the student is now Frank’s responsibility. And hanging over the whole story is a feeling of irony and doom, because we know that very shortly after the story closes, the First World War will begin, and the characters’ idyll will end.

The Gate of Angels (1990), set in Cambridge in 1912, is the improbable love story of an absent-minded physicist and a pragmatic, working-class nurse. They are brought together by a deus ex machina in the form of a bicycle crash. They wake up in bed together, and chaos ensues.

The Blue Flower (1995), Fitzgerald’s last book, is actually the first of hers that I read, back when it first came out. Lured by the rapturous reviews, I gave it a whirl but have to confess that I didn’t get it. It’s an elliptical—perhaps too elliptical, she said darkly—historical novel about the Romantic poet Novalis, and I probably could have used some help understanding all the nuances.

On this point, there is good news! The Footnotes and Tangents slow-read group on Substack will be reading The Blue Flower next year. We’re reading War and Peace together this year (we read and discuss one chapter per day), and it has been a wonderful experience. Interested? Just follow the link to sign up. It’s even free! What do you have to lose?

I haven’t yet mentioned Fitzgerald’s lovely novel The Bookshop (1978). I have a proposal: We didn’t have a Happy Wanderer book club this summer, and I’m wondering whether you might like to read The Bookshop together this fall? It’s short (155 pages), and, for people who don’t have time to read it, there is a wonderful 2017 film of the book, starring Emily Mortimer, Patricia Clarkson, and Bill Nighy. So, readers, for the next few weeks, would you rather have a book club, or regular essays? You can vote here:

Thanks for voting! I’ll let you know the results next week.

How about you, readers? Have you, or has someone you know, enjoyed a late-in-life flowering? Do you have a favorite author who most people don’t know about? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

For those of us not blessed with Fitzgerald’s extraordinary gifts, here’s a little inspiration from Alex Dobrenko, who writes the Substack both are true:

We don’t have to be famous to be happy! We can just “do our little art” and know that people we care about will enjoy it—and we will too!

The quotation and all biographical information in this post come from Hermione Lee, Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life (Knopf, 2015).

Thank you for bearing with me this week, readers. I wrote this a few months ago, before my resolution to write shorter posts. At least the extra words are not mine, but rather those of the infinitely superior Fitzgerald (and also Milton and Auden). Starting next week I will Do Better.

Published my first novel at 66.

Thank you for such a wonderful write-up of Fitzgerald and her fabulous books! I've been a huge fan since I read my first one (Offshore, still a favorite). I've since read them all at, several more than once. They reward a re-reader, and it helps that they are short. I also recently got the Lee biography and PF's book about the Knoxes, both of which I am itching to start.

I am so looking forward to the Blue Flower next year with Simon's slow read. It will be my 4th time reading it, and I'm finally starting to get it!

(And I agree about her Italian book, it didn't grab me either, not like her others have.)