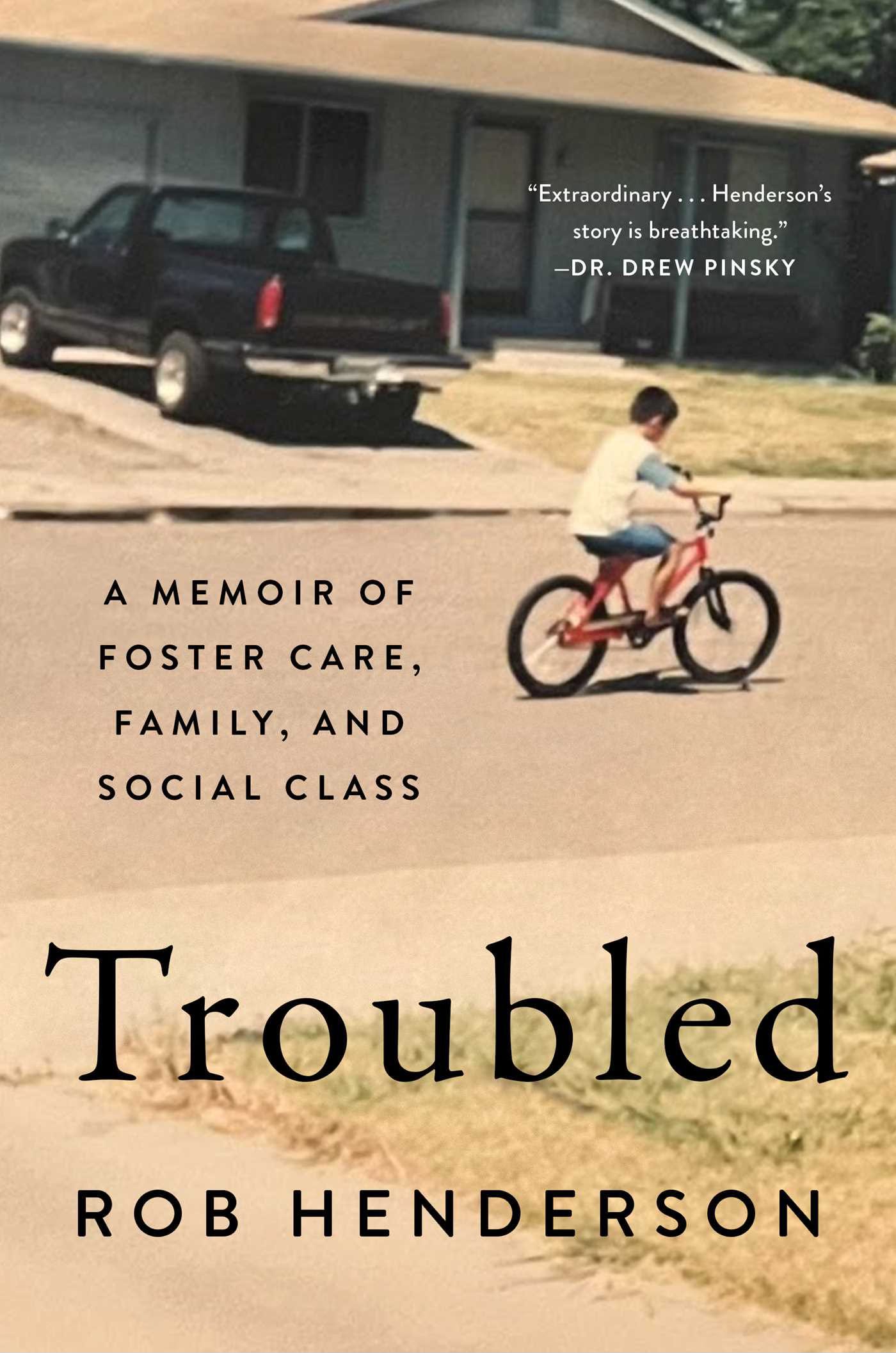

I decided to read Rob Henderson’s Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social Class (Simon and Schuster, 336pp, $28.99) for an eccentric reason: I’m doing a reading challenge this year that includes “a book of cultural critique/commentary by someone who disagrees with you on a major philosophical or political point.” Henderson’s book was blurbed by J. D. Vance and Jordan Peterson—a potent signal to people on my side of the political aisle that this book is Not for Us.

Which is a shame, because Henderson’s book has three valuable lessons for all readers. First, he paints a devastating picture of the suffering of children in chaotic families. Second, he exposes terrible flaws in the foster care system and offers suggestions for improvement. And third, he encourages elites to resist “luxury beliefs, which are the ideas and opinions that confer status on the upper class at very little cost, while often inflicting costs on the lower classes.”

The endorsements by Vance and Peterson should not deter us,1 but we seem to have been deterred nonetheless. With the exception of a mixed review in the Atlantic and a harshly negative and at times deceptive2 review in the Washington Post, the liberal media have ignored Henderson’s book in the weeks since its publication, and he has been unable to find a bookstore willing to host an author event. So I have a specific purpose in writing this review: I encourage my fellow liberals to ignore the plaudits on the right and the dark mutterings about Henderson’s allegedly nefarious motives on the left, and to give this book a chance.

A Childhood of Dread and Chaos

Henderson endured a childhood so wretched and harrowing that his story could have been written by Dickens. The book reads like a suspenseful bildungsroman about an admirable person who triumphed over seemingly insurmountable obstacles. The afternoon I bought the book, I thought I would just dip in for a half hour or so—and eighteen hours later I finished it. Henderson’s story is that compelling.

Henderson was born to a homeless, drug-addicted mother, and he never knew his father. He was taken in by child-protective services when he was three, after neighbors heard him crying, and police discovered him tied up while his birth mother got high. His birth mother was jailed and eventually deported back to her home country of Korea. For the next five years, Henderson would live in ten different foster homes, including one, that of a real-life Mr. Murdstone named Mrs. Martinez, in which he was forced to perform unrelenting and dangerous chores. Henderson characterizes this time in foster care as one of constant dread: “Dread of being caught stealing, dread of punishment, dread of suddenly being moved somewhere else, dread of one of my foster siblings being taken away.”

Even after Henderson was adopted just before he turned eight, he continued to suffer from family chaos. He had eighteen months of normal family life. Then his parents divorced, and his adoptive father, out of spite at Henderson’s mother, refused to ever see or speak with Henderson again. Henderson’s mother began a relationship with another woman, Shelly, and again Henderson’s life settled down for a bit—until Shelly was shot. She endured life-altering injuries, she and Henderson’s mother lost all the family’s money investing in real estate just before the 2008 crash, and Shelly succumbed to a gambling addiction.

Henderson exposes a number of problems in the foster-care system to which we luckier readers may be oblivious. For example, I didn’t know that foster children are moved from home to home every few months in a deliberate attempt to prevent them from bonding with their foster families. This practice is intended to keep the children emotionally available to be taken in by a relative, should one be found, but such instability is terribly destructive to young children’s sense of security and ability to trust. Another issue is foster siblings; Henderson lived in foster homes with as many as ten other kids at a time, and he experienced constant abandonment as foster siblings he cared about were taken away without warning. Finally, readers of Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead may have hoped that her account of the several hours per day of child labor Demon is forced into by a foster father has been exaggerated, but Henderson’s time with Mrs. Martinez confirms that some foster families abuse and exploit the children in their care.

Henderson argues persuasively—and with evidence—that it is family chaos, and not poverty, that is most destructive for children. To mitigate this chaos, he recommends that foster kids be kept in one family or fast-tracked to adoption if there is no parent or relative who can take them. His experience with Mrs. Martinez also demonstrates that much more oversight of foster parents is needed to protect these vulnerable children.

Elites and Luxury Beliefs

Henderson developed his concept of luxury beliefs while he was at Yale. He noticed that many students who came from privileged backgrounds were contemptuous of the nuclear family even though they had benefited from stable families themselves and planned to have conventional marriages in the future. Similarly, these privileged students faced no consequences for their support of such positions as Defund the Police and drug legalization, because they lived in prosperous areas with very little crime. As Henderson notes,

if all drugs had been legal and easily accessible when I was fifteen, you wouldn’t be reading this book. My birth mom was able to get drugs, and it had a detrimental effect on both of our lives. That’s something people don’t think about: drugs don’t just affect the user, they affect helplesss children, too.

It is possible to support significant reforms in policing—as I do—and still think that Defund the Police is a luxury belief that should be criticized. This is personal: When I was in grad school, I lived in a high-crime neighborhood. One night, there was a shootout in the alley next to my building, and a bullet flew through my downstairs neighbor’s window and lodged in the ceiling, just below my head as I slept. When I told a friend about this, a well-dressed man overheard me and scolded me for being “obsessed” with crime.

Maybe I was “obsessed,” but it was not by choice. To paraphrase that joke about Chuck Norris, I might not have been interested in crime, but crime was interested in me. While living in that neighborhood, I was burglarized once and pickpocketed and purse-snatched multiple times. People who live in safe neighborhoods have no idea how violating it is to know that strange men have been rummaging through your underwear drawer; how sad it is to lose cherished mementos and photos; how infuriating it is not to be able to afford to buy another bike and boombox;3 or how time-consuming it is to have to replace credit cards, driver’s license, and IDs over and over again.

I was grateful for the police, because without them our neighborhood would have been still worse. Case in point, one afternoon, I was outside on my balcony and saw a man snatch a woman’s bag. I called the police and was still on the phone with them when they caught the guy. Those who have never had to worry about crime might think I was being a Karen, but it was a comfort to know that the police were there to restore the woman’s property to her and to spare her a trip to the DMV.

Even those who disagree with Henderson about the value of the nuclear family, the police, and drug laws shouldn’t reject the concept of luxury beliefs out of the hand, because luxury beliefs are common on the right too. For example, many elites on the right oppose contraception and endorse harsh prison sentences for low-level drug offenders. Such uncompromising stances give their proponents a reputation for purity and holiness among their followers, but elites don’t have to suffer for these beliefs. They can financially support an unplanned grandchild, and they can call in a favor or pay a top attorney to get their kid’s drug-possession charge dropped. Other Americans aren’t so lucky.

Two more examples: The saber-rattling and warmongering of chickenhawks like Dick Cheney and George W. Bush enhanced their machismo, while around 7000 dead US soldiers and around 300,000 dead Iraqi civilians paid the price. And climate-change denial confers not only social but also economic status on bigwigs who invest in fossil fuels—and ordinary people whose homes are consumed by wildfires or destroyed by extreme weather suffer the consequences. While Henderson discusses luxury beliefs on the left, his concept is useful for all of us when we want to criticize any privileged person, of any political party, who obtains a benefit from a harmful belief.

A Quibble

Henderson’s terrible childhood has given him special insight into the dangers of instability in the foster care system and in families. In addition to his valuable recommendations for how to address the problems in the foster care system, he endorses the military, which he rightly notes is an excellent way to provide structure and discipline for troubled young people. He also argues, convincingly, that military service removes volatile young men from toxic communities at an age when they are most likely to be violent.

However, while Henderson focuses on two valid solutions to social problems—lessening chaos in families and countering luxury beliefs—he doesn’t explore many other routes to helping children. For example, he believes that liberals overemphasize financial assistance and education, and yet one reason he is now happy and successful is that he received financial assistance to attend both Yale and Cambridge.

Another way we can intervene in kids’ lives is through their peers. Henderson’s teenage friends all used drugs, engaged in risky behaviors, and committed crimes. I kept wishing that he could have had access to a friend group that would have supported better choices. This is personal too: One of my best friends, whom I’ll call Linda, had an upbringing as terrible as Henderson’s. She scored a seven out of ten on the Adverse Childhood Experiences scale,4 but she had a large group of college-bound friends who knew how intelligent, courageous, resilient, and dedicated she was. When a school counselor told Linda she wasn’t college material, we were all outraged on her behalf and strongly encouraged her to go to college. Linda did go to college, and then to law school. She is now a top family attorney who helps children and adults escape abusive families. Education works!

Finally, numerous social problems alluded to in the book require systemic, not individual, solutions, for example the gun violence that led to Shelly’s injury,5 the 2008 financial crisis that devoured the Henderson family’s savings, and Henderson’s addiction, for which he received effective, free treatment through the military. All Americans struggling with addiction deserve the same help, but, as Shelly’s untreated gambling addiction shows, few get it. While ridding elites of destructive luxury beliefs and strengthening the nuclear family are crucial measures that Henderson is right to emphasize, we need more weapons in our arsenal than private action for these very tough challenges.

A Final Point about Men

I’ll close with an aspect of Henderson’s book that I found quite refreshing. When discussing the breakdown of the nuclear family, conservatives too often blame women. They characterize us as picky princesses who are unwilling to settle for a nice man, or they complain that we care more about our education and careers than about marrying and having children. They shame single mothers for their supposed promiscuity, selfishness, and irresponsibility. But somehow these conservatives seem unaware of the men who refuse to get married, or who sleep around or abuse or abandon their partners and children.

Henderson doesn’t do this. Quite the contrary, even though his adoptive mother and Shelly were by no means ideal parents, he expresses gratitude for their love and sympathy for the challenges they faced. He also has kind words for his caseworker, Gerri, “a rock in my life, the only person who I felt cared about me” when he was in foster care. But he exposes the men who could have loved, supported, and mentored him and his friends, but were instead absent, incarcerated, indifferent, or—in the case of his adoptive father—cold-blooded and cruel. This book is an important corrective to a conservative tendency to ascribe all the problems in American families to women, and to let men off scot-free. Henderson challenges men to step up.

Henderson wrote his book with two audiences in mind. “I kept thinking about some kid like me out there who might pick this up and draw inspiration, the same way I did as a kid hanging out in my schools’ libraries.” And he asks those of us who have been luckier than he was that “Whatever sympathy you felt while reading my story, please channel it toward kids currently living in similarly unpromising environments.”

How about you, readers? Have I piqued your interest in this book? And what do you think is the best way to help children in troubled circumstances? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

I hope I have persuaded you that Henderson has been unjustly accused and that his book is for us too.

The cartoonist xkcd would like to speak up for another unjustly-accused group:

Mind blown! I didn’t know this—did you?

Full disclosure: I read Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy, enjoyed it, and believe it has some insights to offer about personal responsibility and the challenges of poverty. But since writing the book, Vance has revealed himself to be a sycophantic opportunist (opportunistic sycophant? that too!).

And I don’t get why anyone listens to Peterson’s whackadoo ideas. To take just one example, if we were to follow his advice to eat only meat and nothing else, in a few months everyone’s teeth would be falling out from scurvy.

According to the reviewer, Emi Nietfield, Henderson “argues that the ostensible radicalism of his peers was actually hypocrisy born from self-interest: that privileged undergraduates want the less fortunate to be opioid-addicted obese single parents so that they can get ahead and become even wealthier by comparison” [italics in original].

But this is false. Henderson believes that elites espouse luxury beliefs in order to fit in with peers and/or to raise their social status, but he thinks they don’t realize that these beliefs could harm the less-privileged. One of his motivations for writing the book is to make elites aware of the pernicious effects of luxury beliefs, in the hopes that elites will begin speaking up for healthier ways of living.

Renter’s insurance is not an option in high-crime areas, because it is unaffordable. I looked into getting insurance after I was burglarized but found out that insuring my meager possessions would have cost more than $550 per month in today’s dollars—far more than my stuff was worth. Lucky for me, after a few weeks of lurching around on a broken-down bike I bought for $10 at a police auction, my kind parents gave me money for a new bike.

This is not a test anyone would want to ace. Most people reading this post would score a zero, or at worst a one or two.

A correction: This article originally said that Linda had scored a nine out of ten. She got in touch with me so I could correct the error and also add that she scored an eleven out of thirteen on resilience factors. Resilience factors include, in particular, having a supportive peer group and at least one adult with whom the child has a good relationship. Linda says, “Truly, but for the friends who saw more in me than I saw in myself, I do not know if I would have dared to to do what I have done with my life.”

Shelly was not a victim of a crime; she was shot by accident at a gun range. However, gun violence was still behind what happened to her because she was learning to shoot in response to gun violence in her neighborhood.

Love the review Mari! I too hope many people read this book. I would just add that crime also is psychologically damaging for people. Crime generates anxiety, mistrust, and fear - and its not good to marinate in negative feelings all the time! When you live in a neighborhood with a lot of crime, so much energy goes to vigilance and worry.

Mari your posts are always a joy to read. In this case very much appreciate how you bust through the barriers to understanding that book "blurbing" now creates. Vance and Peterson are "coded" as right wingers, which is apparently all one needs to know for so many people on the left.

But I'd go a bit further here. My motto is: "people are complicated". I try to remember this every time I encounter someone espousing some belief or attitude that I disagree with. I think I have developed this strategy out of necessity because I am a non-lefty academic (an agnostic, I guess, in religion as well as politics); virtually all my colleagues are hard-left politically, and have reflexive beliefs (including luxury beliefs) about many things that they do not actually understand. Also, I am a southerner who now lives in the upper midwest. During my three decades as a transplant, I have found that nobody up here understands the culture of the south, but everyone thinks they do. BUT! I work with these people. We co-teach design studios. We drive thousands of miles around the country with three dozen undergrads every fall. We work on committees that actually accomplish good things. We have a beer together at happy hour every Thursday.

The lesson for me is that no one should be reduced to being "coded"—you embrace that notion here—but also, no one should be represented incompletely and tendentiously. Jordan Peterson may have nutty ideas about diet (I had not heard of this), but he's well-known for big ideas about big things that run contrary to the postmodern/woke catechism. He's an important culture critic; whatever you think of his arguments, he makes thoughtful arguments. Better to refer to him for the substance of his work that to dismiss him for his beefism.

A further quibble: you "beg the question" about climate change. Causation has not been established between anthropogenic climate inputs and weather events or wildfires, but for many this is received wisdom. Al Gore famously stated that "the science is settled". This is not true. For some of us, being skeptical about this is not "luxury beliefs", but a completely honest devotion to open-mindedness.