This Book Isn't What You Think It Is

Negative Capability and What We Can Learn from Going Infinite

A couple of years ago, a shaggy, schlubby, unprepossessing individual started showing up in ads in my New Yorker magazines. “Who is this guy, and what is he doing hanging out with supermodels, athletes, and celebrities?” I wondered.

Oh yeah. Him. But he’s not the subject of this essay. Instead, I hope to persuade readers to remain in a state of negative capability about Michael Lewis’s Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon and to give the book a chance. Reviewers in every major publication have hypothesized that Lewis was conned by a grifter and wrote an apologia for Sam Bankman-Fried.1 Now that Bankman-Fried2 has been found guilty of all seven charges, Lewis’s book might seem even more suspect.

And yet I believe that most reviewers have missed the real point of Lewis’s book, which is not to admire a disturbed and disturbing person who stole $8 billion of his customers’ deposits, but rather to encourage us readers to engage in some self-reflection. Thankfully, the criminal justice system has handled Bankman-Fried.3 But how should we handle ourselves? How can we act in our own lives to minimize the damage the Bankman-Frieds of the world inflict?

So What Is Negative Capability Anyway?

Lewis has said in an interview that he has no idea how his readers will judge Bankman-Fried based on what he has written. His book has, to quote Woody Allen’s film Manhattan, “a marvelous kind of negative capability.”

Granted, Diane Keaton is insufferably pretentious in this scene,4 but negative capability is a useful way of approaching the world nonetheless. The term comes from Keats and refers to the ability to remain in doubt, uncertainty, and ambiguity rather than rushing to judgment. The urge to judge is strong; as New York Times columnist Pamela Paul put it in a recent interview, we often find ourselves “criticizing various things before you had actually read the thing” (the quote appears at 40:00). It can be uncomfortable to resist this tendency and to keep asking questions and examining evidence, but it’s worth the discomfort, because this is the way we learn and grow.

What should we think about Bankman-Fried? If we actually read the book, instead of just reading about it, we discover that Lewis reports his observations straightforwardly and without trying to influence our opinion.5 And yet it becomes abundantly clear that there is something very wrong with Bankman-Fried, and that he is an unsettling person who thinks in a highly unusual way. He is unable to sleep unless other people are nearby, hence his tendency to sleep on office beanbags. He has no childhood friends and treats everyone in his life indifferently at best and exploitatively at worst. He gambles constantly and once used a betting game to publicly humiliate a coworker. He says he is unable to feel happiness. He practices arranging his facial expressions so that he will appear more human in conversations with other people. He misplaces $4 million and doesn’t even care. Is he a psychopath, or is he just chaotic and messed up? Lewis leaves this question open.

A Brief Digression about Caroline Ellison

That being said, no one could read about how Bankman-Fried treated tiny, homely, besotted Caroline Ellison and feel much sympathy for him. Lewis publishes a few of Bankman-Fried’s coldly clinical memos to Ellison, which calculate the costs and benefits of going public about their relationship. As Lewis says, “Sam wanted to do whatever at any given moment offered the highest expected value, and his estimate of her expected value seemed to peak right before they had sex and plummet immediately after.” Twice, when Ellison asks for more acknowledgment and commitment, Bankman-Fried flees not just the country but the hemisphere in a private jet, moving first to Hong Kong, and then to the Bahamas. He justifies these moves as business decisions, but he is also partly motivated by the urge to get away from her.

Caroline Ellison reminds me of Jane Eyre, if Jane Eyre were a tragedy in which the problem was not the madwoman in the attic, but rather the madman in the executive suite. During Ellison’s tearful testimony, while Bankman-Fried snickered at her, I imagined Jane Eyre’s words: “Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong!—I have as much soul as you—and full as much heart!” Rationalists like Bankman-Fried may disagree, but Lewis suggests that abstract ethical principles mean nothing unless we treat everyone, including the people who are closest to us, with justice and mercy.

Useful Advice from Going Infinite

Anyway, it doesn’t matter what we think of Bankman-Fried personally, because Lewis makes it clear that he should not have had so much power in our culture and economy. In Going Infinite and throughout his career, Lewis has argued for the crucial role of unbiased experts to protect us. His book The Fifth Risk takes this point further to make the case that we need experts because we don’t know enough even to know what dangers we face. Similarly, season one of his excellent podcast series, Against the Rules, argues that even though we sometimes resent referees, we need them to ensure that the rules are followed in fields as diverse as sports, science, finance, consumer products, and the criminal justice system.

Bankman-Fried gambled with other people’s money, without their consent, and he got away with it for so long because crypto is poorly regulated. There are no refs to protect us. Because FTX was based in the Bahamas, it was exempt from financial-reporting requirements that US-based companies must meet. FTX had no chief financial officer, and its board of directors was mostly there as window-dressing. Bankman-Fried didn’t even know the names of two of the three members of his board; he told Lewis that “The main job requirement is they don’t mind DocuSigning at three a.m.” The world of crypto is unregulated and thus vulnerable to the depredations of malefactors and the whims of chaos; whether Bankman-Fried is a malefactor or simply chaotic is irrelevant. We should regulate crypto.

Numerous episodes in the book demonstrate that Bankman-Fried was able to amass money and power not only because of a lack of regulation but also because of our worship of billionaires and tech gurus. The more we learn about Bankman-Fried, the more we might wonder why on earth so many people shoveled money at him. But far from being wary of Bankman-Fried, people throughout the book—including the rich, famous, and powerful—wrangled for access to him and his money. They granted him enormous leeway for his incivilities—playing video games during meetings, reneging on his commitments, dressing like a hungover frat boy at audiences with dignitaries, and the like. (As we saw at his trial, when it is not a matter of respecting other people, but rather of saving his own neck, Bankman-Fried is perfectly capable of cutting his hair and wearing a suit.) Lewis shows that when we are deciding whom to trust, we should not be seduced by the siren song of riches and fame. We should trust only those people who have shown themselves to be trustworthy.

“Rational” Effective Altruists vs. Socrates

Of course, Bankman-Fried was an effective altruist, and so one reason people gave him money was because they DID trust him, not just to invest their money, but to “make a global impact for good.” They were apparently unaware of Adam Smith’s insight that “Virtue is more to be feared than vice, because its excesses are not subject to the regulation of conscience.” Whether Bankman-Fried truly intended to help others with his billions or whether it was a scam all along, it is undeniable that effective altruism was a fig leaf that concealed a stunning waste of money. Among other boondoggles, Bankman-Fried spent hundreds of millions on private air travel, donations to political candidates on both sides of the aisle, real estate in the Bahamas, and dubious promotional deals with such minor celebrities as reality-TV has-beens. It is not clear that Bankman-Fried achieved any good at all, let alone sufficient good to offset the costs he imposed on his victims.

In addition, Bankman-Fried belongs to the rationalist community and claims to be unencumbered by normal human emotions. He thus felt comfortable taking wild risks and placing bets that would terrify us normies. FTX was marketed to ordinary people, most of whom lacked training in finance and crypto markets. Had these investors been aware that Bankman-Fried was disbursing their money with wild abandon, they almost certainly would not have placed their trust in him. Many effective altruists from the rationalist community actually did know about his carelessness; they were willing to entrust Bankman-Fried with tens of millions, in spite of being warned repeatedly as early as 2018 of his erratic and unethical business practices. They were so rational that they lacked (or suppressed) such useful emotions as the humility that would have allowed them to listen to advice, or the anxiety that would have prevented them from making bad bets.

And it is impossible to overstate Bankman-Fried’s willingness to make bad bets: As we learned at his trial, he once told Ellison that if he had a weighted coin, where one side would double human happiness and the other would destroy all life on earth, he would flip it, so long as the coin was even slightly weighted toward the good outcome.

It might be rational to look at the odds and flip the coin, but it’s also nuts. I mean, who does he think he is? Thanos? Lewis’s portrait of Bankman-Fried makes it clear that people who are convinced of their superior intelligence and rationality can be dangerous. They are ignorant of their own blind spots: They don’t know what they don’t know—and they don’t even know THAT they don’t know. We are better off following Socrates, who was wise because he knew that he knew nothing. Negative capability, in other words. Listening to other people and honoring our emotional responses can foster a Socratic openness, and maybe, eventually, wisdom too. One final message of Lewis’s book, then, is that our normal human emotions in all their messy irrationality—our love, loyalty, generosity, insecurity, guilt, and fear—are better ethical guides than pure rationality.

A Final Pitch

Because Lewis remained in a state of negative capability in his conversations with Bankman-Fried, he was able to learn far more about him and his subculture than could a judgmental outsider. Similarly, if we give Going Infinite the benefit of the doubt in spite of what we have heard about it, we will be rewarded with a glimpse into—and warning about—a person who thinks and feels very differently from us. We might even be inspired to suspend judgment and open ourselves to learning something new in our own relationships and lives.

We’ll also be rewarded with a fun read. The book is suspenseful and surprising, and it includes a couple of logic puzzles that you can try out with friends. (Take this question, which Bankman-Fried was asked at a job interview: You have two normal dice. If you toss them both, what are the odds that a three will appear? See this footnote6 for the answer.) Lewis closes the book with an ironic and poignant allusion to Citizen Kane; if you read the book, you will discover why Bankman-Fried’s Rosebud is a tungsten cube.

How about you, readers? Have you read (or read about) Lewis’s book? Has there been a time when you listened to the other side on an issue you care about, and you changed your mind in response to what you learned? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

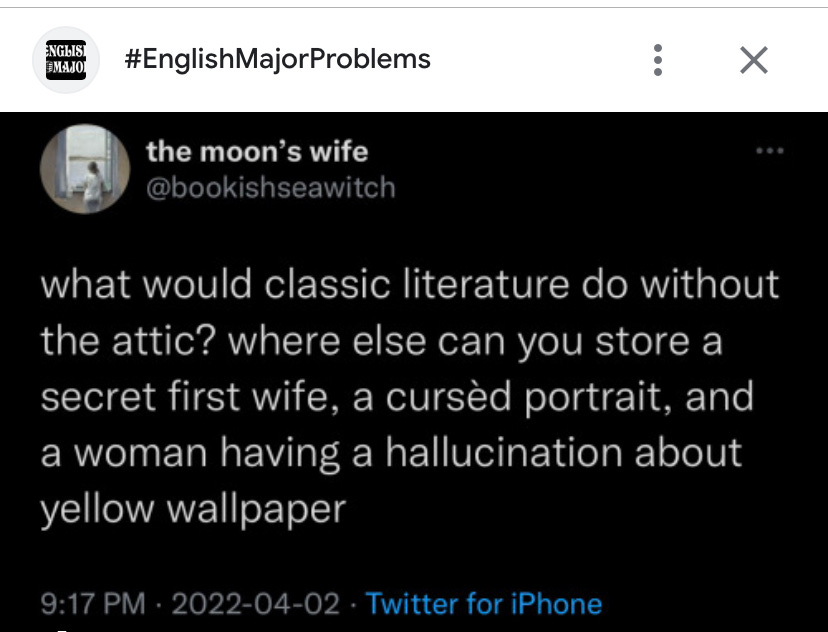

Speaking of Jane Eyre, here’s a cute meme, to which some commenters added another literary joke:

drwcn: cellars. obviously.

ed-edward-blackbeard: Can’t. The cellar is full of Amontillado.

ceekari: Where? I don’t see it

cal-is-a-cuddlefish: Just down here. Come this way and I’ll show you

Tee hee! Whatever you do, don’t go into that cellar!

Hashtag not all reviewers. Cody Kommers, for example, makes the convincing case that Lewis has achieved his goal, which is to answer the question, “Who is Sam Bankman-Fried?” Kommers concludes, “I do think that we need to judge books, if not by their cover, then by the fulfillment of promises made in their introduction. Michael Lewis kept his promises.”

I decided not to use Bankman-Fried’s self-bestowed nickname, SBF, because of this Reddit post. Bankman-Fried has been convicted of stealing billions, and it feels inappropriate to call him by a cutesy nickname.

The jury’s verdict makes me feel patriotic about our system of trial-by-jury, in which justice is meted out by a group of ordinary people who consider the evidence and arguments on both sides before arriving at their verdict. In fact, as this essay will argue, it is a good practice with every issue to look at evidence and then to ponder and discuss before we judge.

Woody Allen, here as in so many of his films, depicts adult women as overbearing harpies who make terrible romantic partners, in contrast with teenaged girls, whom Allen depicts as wise beyond their years and embodiments of pure goodness. But I digress.

All details and quotes that aren’t otherwise cited come from Lewis’s book.

Did you think it was one in three? Wrong! (Don’t feel bad; I got it wrong too.) My mathematician husband explains the answer: Each die has a five-in-six chance of NOT showing a three. So 5/6 x 5/6 is a 25/36 chance of NOT getting a three. Ergo, the chance of rolling a three is 11/36, or slightly less than one in three.

Thank you for advocacy on behalf of negative capability! Sometimes I feel like that's all I'm really trying to aim for in what I write, maybe almost to a fault.

SBF-like figures are troubling and make me impatient with the times we're stuck with. Where will it end for him? Also now I may have to go rewatch the Michael Fassbender version of Jane Eyre.

Matt's answer to the puzzle is easily visualized by making a chart of all 36 possible roll outcomes. From there we can count 11 in which one of the dice shows a three. Our instinct of counting 12 must come from counting the 3-3 combination twice?