This is the second article in a two-part series. Last week I wrote about how it is difficult to make rational decisions in a crisis when we are overwhelmed by fear. I offered three strategies for calming our fears so that we can make smart, balanced decisions.

Today’s article may be a heavy lift for my readers on the left, because I argue that in crises like the pandemic we are better off with fewer restrictions that are carefully targeted, rather than with draconian restrictions that are imposed on everyone regardless of their vulnerability and that are retained even after conditions change. I will supply evidence to support my point, and I hope that readers will approach this article with an open mind.

Among the many reasons I love living in Switzerland is that during the pandemic the Swiss authorities protected the health of the population while minimizing damage to the economy, our mental health, and children’s education.

The Swiss Approach

At the start of the pandemic, Switzerland had the second-highest per capita infection rate in the world, just behind Italy. This was because tens of thousands of people who live in Italy cross the border into Switzerland every day for work, and by the time the Swiss authorities closed the border in mid-March 2020, Covid infections had already spread widely. Switzerland had two other disadvantages that made it more vulnerable to the pandemic: It is very densely populated (comparable to New Jersey, which is the most densely populated state in the US); and its population is significantly older than the world average of 31 years, with a median age of 43 years (the median age in the US is 38.5 years).

Nonetheless, the Swiss health authorities were reluctant to impose draconian measures and instead favored restrictions that offered the most benefit with the least collateral damage:

At the start of the pandemic, indoor gatherings and large outdoor events were prohibited. While many outdoor events resumed in the summer of 2020, at least some restrictions remained on large indoor gatherings until early this year.

For several weeks at the start of the pandemic, schools were closed. After that, schools were reopened and have stayed open for entire duration of the pandemic.

For several weeks at the start of the pandemic, all indoor businesses except grocery stores, gas stations, and pharmacies were closed. Indoor businesses were allowed to reopen in stages, at lowered capacity, thereafter. Nearly everything was open again by the summer of 2020 (some businesses like movie theaters and gyms stayed closed longer).

The authorities developed a free, voluntary, contact-tracing app that was downloaded by more than two million people within three weeks of its launch. The app has been credited with identifying 500–1000 possible infections per month.

No parks or other outdoor areas were ever closed, and health authorities encouraged people to stay active outside.

Masks were only required indoors nationwide beginning in October 2020. Masks have never been required outdoors (except in extremely crowded conditions) or on schoolchildren below age twelve (age nine in some cantons).

Once vaccines were available, large indoor events resumed. Attendees had to provide proof of either vaccination or recovery from Covid, or to show a negative Covid test.

Until this spring, Covid tests were free for anyone who had symptoms or who came into contact with an infected person. Affordable rapid self-tests have been readily available for everyone since early in the pandemic.

Throughout the pandemic, the authorities have encouraged such low-cost health measures as vaccination, ventilation, socializing outdoors, and working from home.1

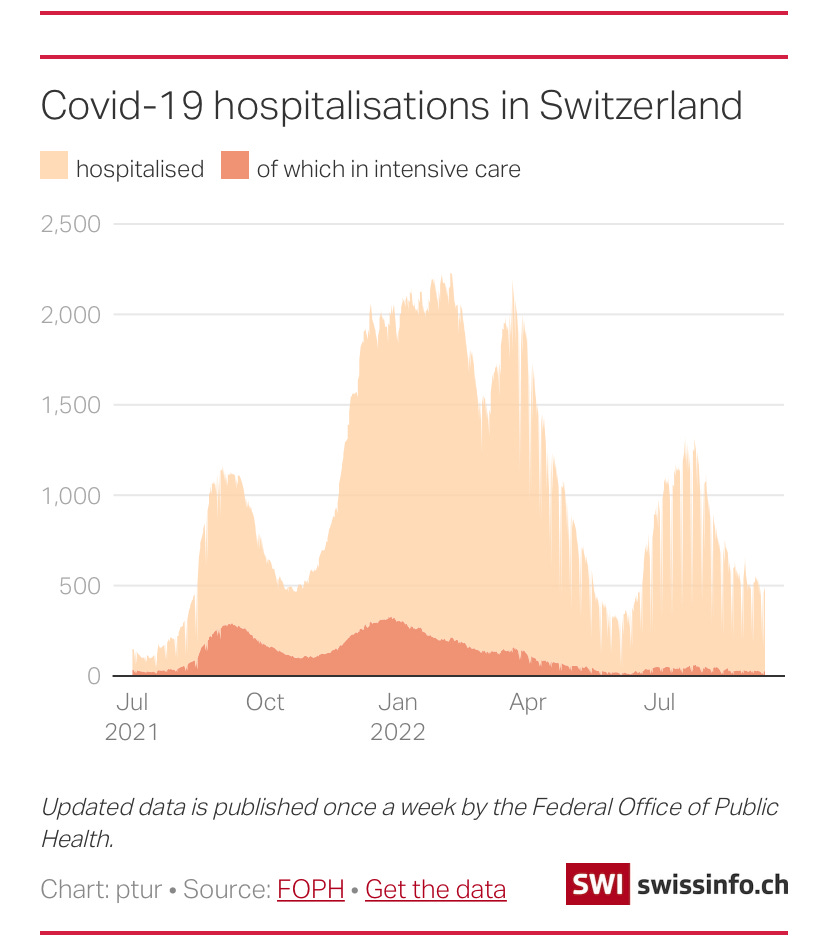

This year, on February 17, the authorities lifted all pandemic restrictions except the mask mandate in healthcare settings and on public transportation. On April 1 that mandate was lifted too. Ending the restrictions did not cause a crisis; quite the contrary, as you can see from the graph below, hospitalizations decreased from February on:

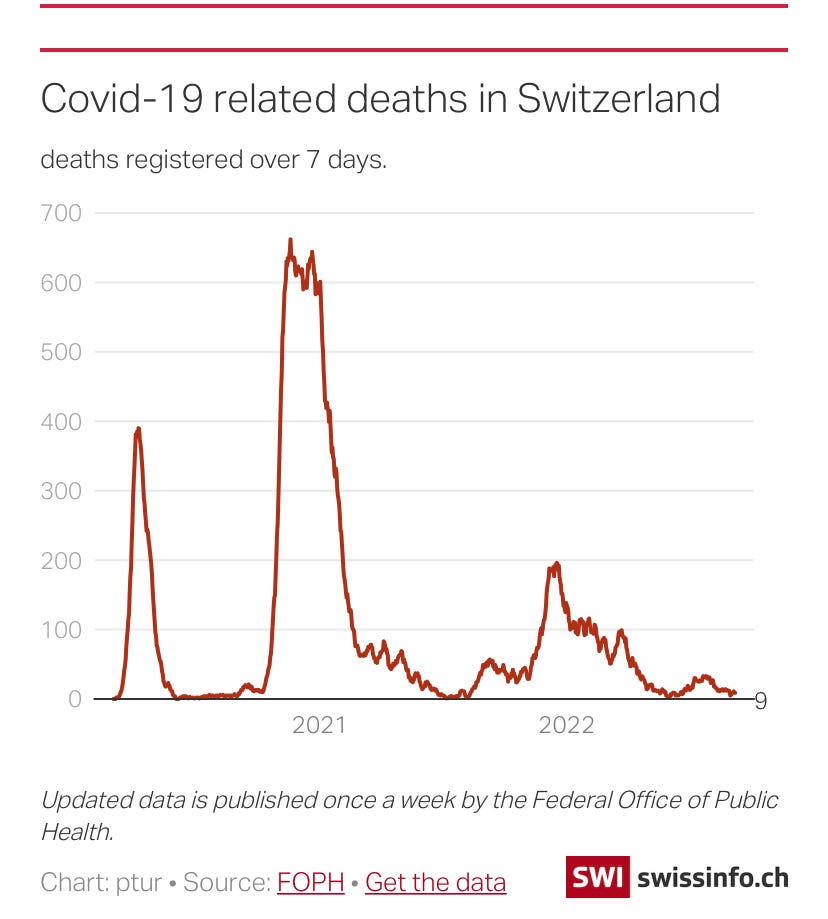

Deaths did too:

Switzerland wasn’t perfect; their vaccine roll-out was somewhat slow, and there were a couple of superspreading events in the fall of 2020 (amusingly, one was a yodeling retreat—peak Switzerland!). As in every country, Switzerland had some Covid-deniers and protests. That being said, if you look at the statistics, Switzerland did remarkably well. As of the end of September, there have been fewer than 14,000 deaths from Covid in Switzerland out of a population of 8.6 million, or 1 in 629 people. By comparison, in the US about 1 in 330 people has died from Covid. (Switzerland and the US have similar percentages of people who are fully vaccinated—about 69 and 68 percent respectively.)2

Some Other Comparisons, and a Hypothesis

To reinforce my point, I’ve gathered statistics from the countries that surround Switzerland, which are demographically and geographically similar, as well as from the Czech Republic, where I used to live. In every case, stringent pandemic restrictions don’t correlate with low death rates.

Italy had extremely draconian restrictions (long-term school and business closures, stay-at-home orders, and indoor and outdoor mask mandates), and about 177,000 people have died of Covid out of a population of about 60 million, or a rate of 1 in 339.

France had somewhat draconian restrictions (intermittent school and business closures, indoor and outdoor mask mandates, and, at the beginning of the pandemic, stay-at-home orders), and about 155,000 people have died out of a population of about 67 million, or a rate of 1 in 432. (Austria was similar to France in both restrictiveness and its death rate of 1 in 429.)

Germany’s restrictions were less draconian than in France and Italy, but more so than in Switzerland; about 150,000 people have died in a population of about 83 million, or a rate of 1 in 553.

The Czech Republic had extremely draconian restrictions (the longest school and business closures in the EU as well as indoor and outdoor mask mandates) and yet had one of the worst death rates in the world—about 41,000 people have died out of a total population of about 11 million, or a rate of 1 in 268.

Of course correlation doesn’t imply causation,3 but this comparison ought to demonstrate that draconian restrictions aren’t necessarily helpful. The evidence suggests that success during the pandemic is caused by other factors than how stringent the rules are. One obvious factor is economics; Switzerland is much richer than Czechia and Italy, for example. Another is whether the people in the country are willing to follow the rules; as David Leonhart puts it, “Masks work, but mandates haven’t.” I have also wondered whether Italy was so badly affected because many Italians live in multigenerational homes, which would leave seniors particularly vulnerable to infection. And it is possible that Czechia suffered so many deaths because it has high rates of smoking and drinking.

The Secret to Switzerland’s Success

So, why was Switzerland—older and densely populated; hit hard at the very start of the pandemic, when there were no vaccines or treatments and the population was immunologically naive; and with open schools and businesses—able to protect its population so well? One crucial advantage Switzerland has, that we don’t enjoy in the US, is a culture of rule-following and trust in institutions. As just one example, imagine what would happen if the US government offered a contact-tracing app. I doubt that a quarter of the population would quickly download it, as happened in Switzerland!

But lost in conversations about the Swiss culture of rule-following is an important fact: Swiss authorities tend to impose only those rules that the population will agree are sensible and necessary.4 After the first weeks of lockdown, the authorities turned to interventions that were highly effective and not particularly burdensome (vaccines, ventilation, working from home, rapid-testing, contact-tracing, outdoor events); and those that imposed some costs but were also effective (limited capacity for indoor businesses, masks indoors and on older children in schools, and bans on large indoor gatherings). With the exception of the school closures during the first weeks, the authorities never required interventions that hurt people while offering little benefit (such as closures of parks and schools, stay-at-home orders, or mask mandates for young children). Many other countries and parts of the US, by contrast, imposed measures that came with high costs and offered little benefit,5 with the result that some people disobeyed the rules, others got angry, we became even more divided than we were before, and the pandemic continued to spread.

The Other Secret

Thank you to my compatriots on the left for sticking with me thus far. Now I’m going to risk alienating readers on the right, because the other secret to Switzerland’s success is democracy and a robust social safety net. Switzerland is so democratic that they have elections four times a year. In contrast to Republican demands that voting ought to be as difficult as possible, it is easy to vote in Switzerland. Before an election, all adult citizens receive a voter-information packet and ballot in the mail (all adult citizens are automatically registered to vote). Most people vote by mail, but those who prefer to vote in person do so on weekends so they don’t have to sacrifice a day’s pay or risk losing their jobs. No wonder the Swiss pandemic restrictions kept people safe while being sensible and tolerable—politicians know that they ignore voters’ wishes at their peril!

In addition, Switzerland, like every developed country except the US, has universal healthcare. Workers here are entitled to four weeks’ paid vacation, in addition to public holidays, and they can take paid sick leave whenever they need it. The Swiss have more time for relaxing, exercising, and being with family than we do; the work week is typically 41 hours, and it is not acceptable for employers to pressure workers to come in sick or put in the long hours that are normal in the US. Universal healthcare; adequate sick leave, vacation, and leisure time; and a prosperous economy have made Swiss people much healthier than Americans: The Swiss life expectancy is 84 years, while in the US it has dropped to only 76.1 years.

I tricked you. This has been an election post all along. The unhindered right to vote and a strong social safety net are crucial tools for protecting citizens during pandemics and other crises. On election day next month, we ought to vote for politicians who will protect voting rights and fight for the same benefits that other developed countries enjoy, for our health, happiness, and national security.

So what do you think, readers? In the future, can we work together to balance risks and benefits and to make our country more secure for all our people? If you could wave a magic wand, how would you handle a future pandemic or other crisis? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Let’s close with a charming Swiss tradition, the Alpabzug, or cow parade. Every spring, farmers drive their cows high up into the mountains so that they can graze in cool comfort, without flies or other pests to trouble them (except for cow-besotted hikers like me, or terrified dogs like mine).

The cows help to maintain the terrain at high altitudes by eating weeds, fertilizing the grass, and churning up the turf with their hooves. At the end of the summer, the cows parade back down to their winter quarters. The farmers dress up in traditional costumes and deck their cows out in flowers and fancy bells. The cow who has given the most milk gets to be queen of the parade. People come to enjoy the show, to buy cheese, and maybe even to share some schnapps with the farmers.

The video below, from an Alpabzug last year, gives a sense of the marvelous cacophony of the cowbells, the colorful floral crowns, and the stunning scenery of the Lauterbrunnen Valley.

The Swiss take ventilation seriously. Throughout the pandemic—including in winter—the windows in my daughter’s school were kept open. It’s even in our lease that we have to open the windows for at least a few minutes every day to allow the air to circulate.

An even better comparison is with New Jersey. As noted above, New Jersey and Switzerland have similar population densities, and both places were hit early and hard by the pandemic. (Two differences balance each other out: New Jersey has a somewhat younger median age of 39 years, and Switzerland is somewhat richer than New Jersey.)

New Jersey had much stricter pandemic restrictions than Switzerland—longer business closures; closures of parks and outdoor areas; stay-at-home orders; school mask mandates until this spring for all children, including those as young as age 2; and school closures that in some districts lasted through the end of the 2020–21 school year. As of the end of September, 34,700 people have died of Covid in New Jersey, in a total population of about 9.2 million, or a rate of 1 in 265.

If anything, the causation is probably working in the other direction. Hard-hit places like Italy and New York City reacted to so many terrible deaths early in the pandemic by becoming extremely restrictive and then retaining the restrictions even after the pandemic waned.

I can’t understand why we didn’t at least try ventilation and rapid-testing, or why parks and schools stayed closed for so long in so many places.

Great post. Two things caught my attention, besides your very interesting comparisons among COVID effects in different countries and factors that help explain them. One: I don't get why it would be "heavy lifting" for a lefty to encounter an argument that some COVID restrictions, in retrospect, went too far. That suggests that lefties are generally intransigent, which I hope isn't true. I have a lot of lefty friends (I am an academic), and there's a lot of reflective discussion about the unintended consequences of measures that were too drastic (such as extended school closings), as well as measures that proved completely wrongheaded in retrospect (such as closing beaches, or prohibitions on being outdoors).

The second is the statement about how Republicans want to make it "as difficult to vote as possible". Perhaps there are Republicans who want this, but I don't know any. I also have a lot of friends who vote Republican (they're not academic colleagues, ha), and they are concerned about ballot integrity after an election during which election-integrity rules were suspended in many places because of COVID. They are also concerned about practices such as "ballot harvesting", legal in some states, which includes allowing activist foot-soldiers (paid by partisan organizations, sometimes paid by the ballot) to collect ballots and deliver them (to post offices or drop boxes), which breaks the "chain of custody" for the ballot. It is a system that can be abused, and certainly it is abused to some extent.

When you imply that the US should be like Switzerland in terms of voting practices, I think you must take into account something else that you mentioned about cultural distinctions: the Swiss as rule-followers. I think Switzerland is a very high-trust society (I've been there, traveling from low-trust Italy, and the cultural difference between those two is immediately obvious, as reflected in things like incidence of petty theft, sexual harrassment on crowded buses, or tolerance for littering.) That same rule-following instinct that you believe limited COVID transmission also sustains trust in election integrity.

And I'm curious about Swiss voting practices. I assume the Swiss postal system is run with great professionalism, that there is no ballot-harvesting, and no drop-boxes.

In any case, there are principled arguments being made in the US (weirdly enough, only ever by Republicans!) in support of election integrity. From my perspective, these are common-sense arguments, made by people who are not out to inhibit voting, but who would simply like to feel the same level of trust in election processes that the Swiss enjoy.

I loved those cows at the end !