I ran across a fascinating moral puzzle in a novel I read recently, The Pleasing Hour, by Lily King.1 Here’s the puzzle, which I have rewritten and expanded.

Five people are on a Gilligan’s Island-style cruise: Allan, Bob, Caroline, David, and Edward. Caroline and David are a couple, but everyone else is a stranger. As was the case with the S.S. Minnow on Gilligan’s Island’s ill-fated “three-hour tour,” this ship capsizes in a storm. (For younger readers who did not spend their childhoods watching reruns on syndicated television and want to understand this allusion, or for older readers who would like to feel nostalgic, or for anyone who would like to have a catchy sea chanty stuck in their heads, here is the show’s theme song.)2

The five passengers swim to safety on two different desert islands.3 Unfortunately, Allan, Bob, and Caroline are stuck on one island, David and Edward are stuck on the other, and there is no way to get between the two. After a short time, Caroline is missing David terribly and is desperate to be with him again. She goes to Bob and asks if he can help her get to the other island. “I have no idea how to do that,” Bob says. “Sorry, but I can’t help you.” Caroline then goes to Allan and asks for his help. Allan says, “Well actually, I DO know how to get to the other island, and I can take you there. But first, as payment, you will have to have sex with me one time.” Caroline agrees, they have sex, and Allan takes her to the other island.

When they get there, Caroline tells David what she did in order to be with him. David is so angry and disgusted that he repudiates Caroline and returns to the first island with Allan, leaving Caroline and Edward together on the second island. Edward comforts Caroline, takes her in, and protects her. They eventually become a couple.

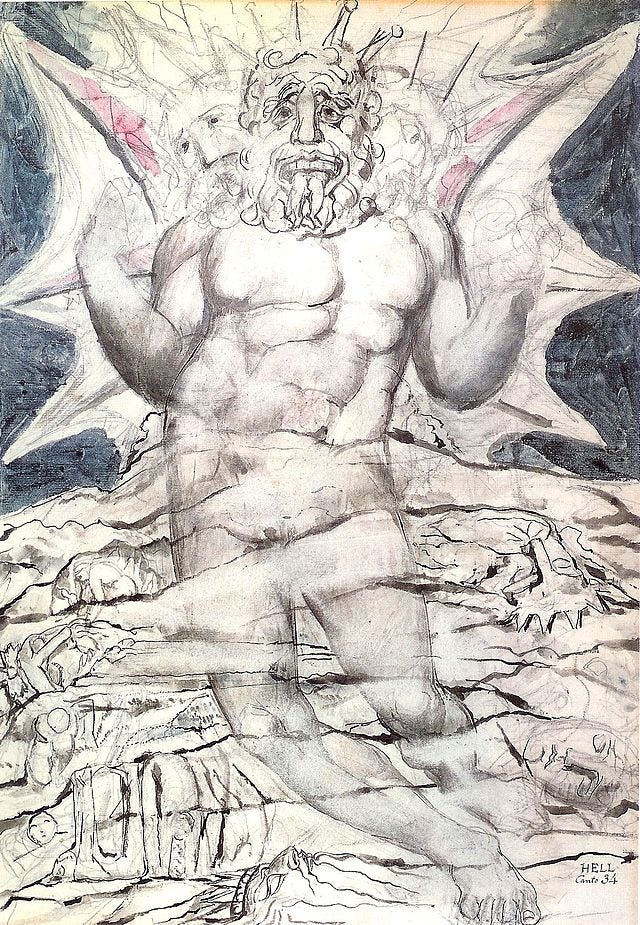

Now for the ethical puzzle: How would you rank these characters based on their morals, from best to worst? And why do you rank them that way? I will give you my own answer below, but I really do want you to think about how you would answer these questions, and I don’t want to prejudice your answers with my own thoughts beforehand. So here is a picture of the Elaphite Islands—on which you can imagine our characters have been separately marooned—from a trip our family took to Dubrovnik several years ago. You can look at the picture while you think about your answer.

First, an Introduction to Moral Foundations Theory

Moral Foundations Theory is an idea developed by social and cultural psychologists, most notably Jonathan Haidt,4 to explore the “intuitive ethics” behind how people think about moral issues. In contrast with other ethical theories, which tend to work from single principles (for example Kant’s Categorical Imperative) or a list of rules (for example the commandments in Judaism and Christianity), Moral Foundations Theory attempts to identify and categorize the philosophical underpinnings of the ethical rules across cultures. The theory argues that all human beings base our moral positions on mixtures of five foundations; every individual will find some foundations more important than others (and, according to Haidt and his coauthors, many of us reject some foundations entirely).

Care vs. harm

Fairness vs. cheating

Loyalty vs. betrayal

Authority vs. subversion

Sanctity vs. degradation

I think that these foundations are pretty self-explanatory, with one possible exception: The final foundation covers not only religious ideas of sanctity (keeping kosher or not taking God’s name in vain, for example), but also physical purity and the need to purge the profane from sacred spaces, especially in matters of sex. The original theory included only five foundations, but some psychologists are proposing that a sixth foundation, liberty vs. oppression, be added. Readers who are interested in a fuller discussion of Moral Foundations Theory should check out Haidt’s book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion.

I thought that it would be helpful to look at Moral Foundations Theory through the lens of a particular example, and then the universe sent me this desert-island puzzle. So, do you have your own moral hierarchy in mind? Ready to explore?

Why Angel Clare is English Literature’s Greatest Monster

When I read the puzzle, I was immediately struck by how obvious the moral hierarchy seemed to me. (Maybe it was the same for you?) Here’s my ranking: Edward is the most moral, while Caroline is the second-most moral. Bob is in the middle. Allan is a very bad guy, but I put him only in spot number four. I reserve the prize for most evil for David.

Here’s my reasoning: Allan is an amoral opportunist who wants to exploit someone in order to seize a benefit for himself. That is caddish behavior, no question. But Allan doesn’t know Caroline; he has no prior commitment or obligation to her. So from his perspective, he might as well give it a try. Allan’s sin is to take advantage of a vulnerable person for his own ends, but David’s sin is much worse—he betrays the person to whom he ought to have a duty to love and protect, his partner. Think about it: When Caroline told David what had happened, his reaction was not to feel terrible for her and ask whether she was ok, much less to show gratitude for what she put herself through for him. (And why didn’t David try to get to Caroline’s island? If he had just shown a bit of gumption, they wouldn’t be in this mess now.) David refused to consider Caroline’s perspective and instead put more weight on her infidelity than on her feelings and worth as a human being. At the end, when David aligns himself with Allan rather than with Caroline, he reveals that he values male dominance more than one’s commitment to one’s partner. Edward, by contrast, acts out of pure, disinterested kindness and generosity. Caroline is a stranger, and yet he comforts and protects her with no apparent ulterior motive.

So who is this Angel Clare, and why is he a monster? Because he’s just like David. In Thomas Hardy’s novel Tess of the D’Urbervilles, Angel idolizes Tess, thinking she’s a flawless, pure maiden. When Tess reveals, on their wedding night (and after Angel has just confessed to a previous affair) that she has been raped and is no longer a virgin, Angel is so disgusted by her impurity that he casts her off and throws her, penniless, out into the harsh world—all the while believing himself to be entirely virtuous. Your top literary villain may be Iago or Uriah Heep or Dolores Umbridge or Philip Larkin’s mum and dad, but you will not persuade me. For me there is no villain in all of English literature more evil than Angel Clare.5

In moral foundations terms, my ranking and my outrage at David (and Angel Clare) reveal that I place the highest value on the ethic of care (Edward) and none whatsoever on sanctity or on authority (David). In addition, loyalty and fairness are very important to my understanding of the story. In my view, Caroline sacrificed herself—she submitted to a traumatizing and even disgusting experience—out of a higher loyalty to David, while David refused to sacrifice even a moment’s thought for her.

Steel-Manning Some Other Rankings

As we’ve seen above, how we rank the characters reveals which foundations we value the most. I disagree with each of the rankings I discuss below, but I will be steel-manning them in order to explore the best case for each ranking, and for the different moral foundations beneath them. (Steel-manning is the opposite of straw-manning: When you straw-man your opponent’s argument, you characterize it in the weakest and least charitable way. It’s easy to win a straw-man argument in your own mind, but you are unlikely to persuade your opponent, who will be thinking, “But that’s not what I meant!” When you steel-man your opponent’s case, on the other hand, you give it its strongest formulation and argue with that version, instead of with an invented weaker case. Steel-manning is good practice in all discussions—you’re more likely to learn something and to persuade others when you use it. See this article for more information on straw- and steel-manning.)

Allan is the most moral. I know this sounds nuts, but hear me out. Allan has figured out how to get off the island. (Did he build a boat out of driftwood? Did he observe the tides and calculate when a sandbar linking the islands will appear? Did he train a pod of dolphins to tow him around? Did he, like Philip Petit at the World Trade Center, shoot a cable over to the other island and learn how to tightrope-walk across?)

Whichever fanciful scenario we imagine, it is undeniable that Allan has attained tremendously valuable knowledge through some combination of superior intelligence, daring, and hard work. In terms of Moral Foundations Theory, Allan’s abilities and knowledge confer authority. The fairness foundation is relevant here too. Allan has something of value; why should he not be paid for it? If we emphasize the authority and fairness foundations, Caroline would come in second place (because she respects Allan’s authority and pays what Allan considers to be a fair price for his expertise) and David would be in third place, because he puts himself under Allan’s protection at the end. Edward would be the worst one in this ranking, because when he takes in Caroline he subverts Allan’s leadership and David’s status as Caroline’s partner.

Caroline is the most moral. In The Pleasing Hour, the two main characters put Caroline at the top of their ranking. Why? Because Caroline sacrifices her body and convention for the sake of love. She shows her faith in the future and her open-heartedness when she begins a relationship with Edward after having been so badly treated by David. She puts caring and loyalty first but obviously values the fairness foundation as well. She could easily have lied to David and lived happily ever after, but instead she chose to be honest with him, at what turns out to be great personal cost. In addition, when Caroline accepts Allan’s proposition, she is following that Spanish proverb, “Take what you want, and pay for it.” If we put Caroline at the top based on the caring and loyalty foundations, Edward is a close second because of his disinterested generosity and protectiveness.

David is the most moral. If we place the most importance on the sanctity, authority, and loyalty foundations, David is the most moral. Caroline’s infidelity not only betrays David, but it degrades the purity of their bond. She has let another man inside her body, rendering it unclean. Caroline also violates the fairness foundation: What if Allan has made her pregnant? Caroline risked bringing another man’s child into her partnership with David and forcing him to take on another man’s work without compensation. Even worse, Caroline, by taking the initiative, subverts the traditional hierarchy in which men are above women—where men are the “head” and women are the “heart.” David should have been the one to resolve the problem; Caroline was getting above herself, and chaos was the result. When David repudiates Caroline, he is demonstrating a higher loyalty to the principles of fidelity and chastity and is reasserting his place at the top of the male-female hierarchy. And when he goes to the first island with Allan, leaving Caroline behind, he reestablishes the borders between pure and impure, keeping that which is unclean separate from that which is righteous, thereby protecting righteousness from contamination. In this reading, David is the one who sacrifices himself in the service of a higher law. Caroline and Edward, who continue to live in sin, are at the bottom of this moral hierarchy.

What about Bob?

One final note. I suspect that no matter how we ranked the other characters, we all placed Bob in the middle, as I did. He’s not going to be at the top of anyone’s list. Which makes sense: He is a bystander who has opted out of the entire problem and thus appears to be perfectly neutral. But, in closing, I’d like us to think about Bob a bit more deeply, because I suspect his situation approximates our own better than that of the other characters. Most of the time, we drift through our daily routine, while ethical dilemmas swirl all around us. To continue the nautical metaphor that runs through this essay, what if we were to grab the rudder and steer toward a better harbor? What if Bob had responded with action rather than passivity? What if he had said, “Well, I don’t know, but maybe Allan does. Let’s go ask him”? Allan would have been unlikely to make his exploitative proposition in front of another man. Maybe the three of them, working together, could have struck a deal and managed to get off the island without anyone’s having to sacrifice or submit to anything. It is true that in some situations we’re genuinely unable to help and ought to stay out of it. Often, though, we’re confronted with situations where, while we could get away with being neutral, the most ethical choice is in fact to act.

OK, readers, how did you rank the characters, and what reasoning did you use? And have you ever decided not to be a Bob, but instead to speak up and take action? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Here’s a fun performance of a sea chanty with which all my fellow choristers are no doubt familiar. Some of the YouTube comments are pretty amusing, too:

Ship’s crew: Starts singing. A sailor who got drunk early in the morning: “Ah no, here we go again.”

Me making a mental note— “Never get drunk on a ship with an Irish crew.”

Never ask a man his salary, a woman her age, or a pirate what to do with a drunken sailor.

Highly recommended!

Who besides me had a huge crush on the Professor?

As is so often the case with ethical puzzles, there are disturbing gaps in this story. What happened to the crew? Did the Skipper and Gilligan escape to yet another island? Did they just drown? The people who created the puzzle don’t seem to care, but I’m curious!

Full disclosure: Haidt was a friend of a friend when I was in grad school in the 90s, and we had some fascinating conversations at parties. He was beginning to develop the ideas that became Moral Foundations Theory, and I took a beta version of the test Haidt created for his research on disgust, which led to the sanctity vs. degradation moral foundation. As I recall, my test results revealed that I had extremely low levels of disgust in all categories, which Haidt found interesting. (Women tend to be more easily disgusted than men, perhaps unsurprisingly.)

This is from Shari even though it looks like it's from Mari: Very interesting dilemma, Mari. I agreed with you on the first two, but I put David third (although after reading your thoughts I would consider ranking him lower. I had Bob fourth since he just stood by when he might have made a positive difference. And I chose to rank Allan, the opportunist, as most unethical. However, lots to think about after reading your comments.

I loved this piece, but for different reasons that I’m still working through and cannot articulate adequately. But, in summary, through a couple of years of mindfulness practice I’ve ended up as a moral sceptic.

So my reaction to the dilemma is that if everyone focused more on their desired outcomes and less on their feelings about ‘shoulds’ they would all be happier. I know this is a rubbish argument, but it’s intuitive and still founded in a nascent dislike of our (including my own) reflexive judgementalism.