A few recent news stories have compelled me to write about what should be such an obvious idea—that none of us is perfect, and that even rich, powerful people can be wrong. Unfortunately, when rich, powerful people are wrong, they can hurt others. On the other hand, when they listen and learn from mistakes, we all benefit. So how do we get them to listen?

But first, a story from history

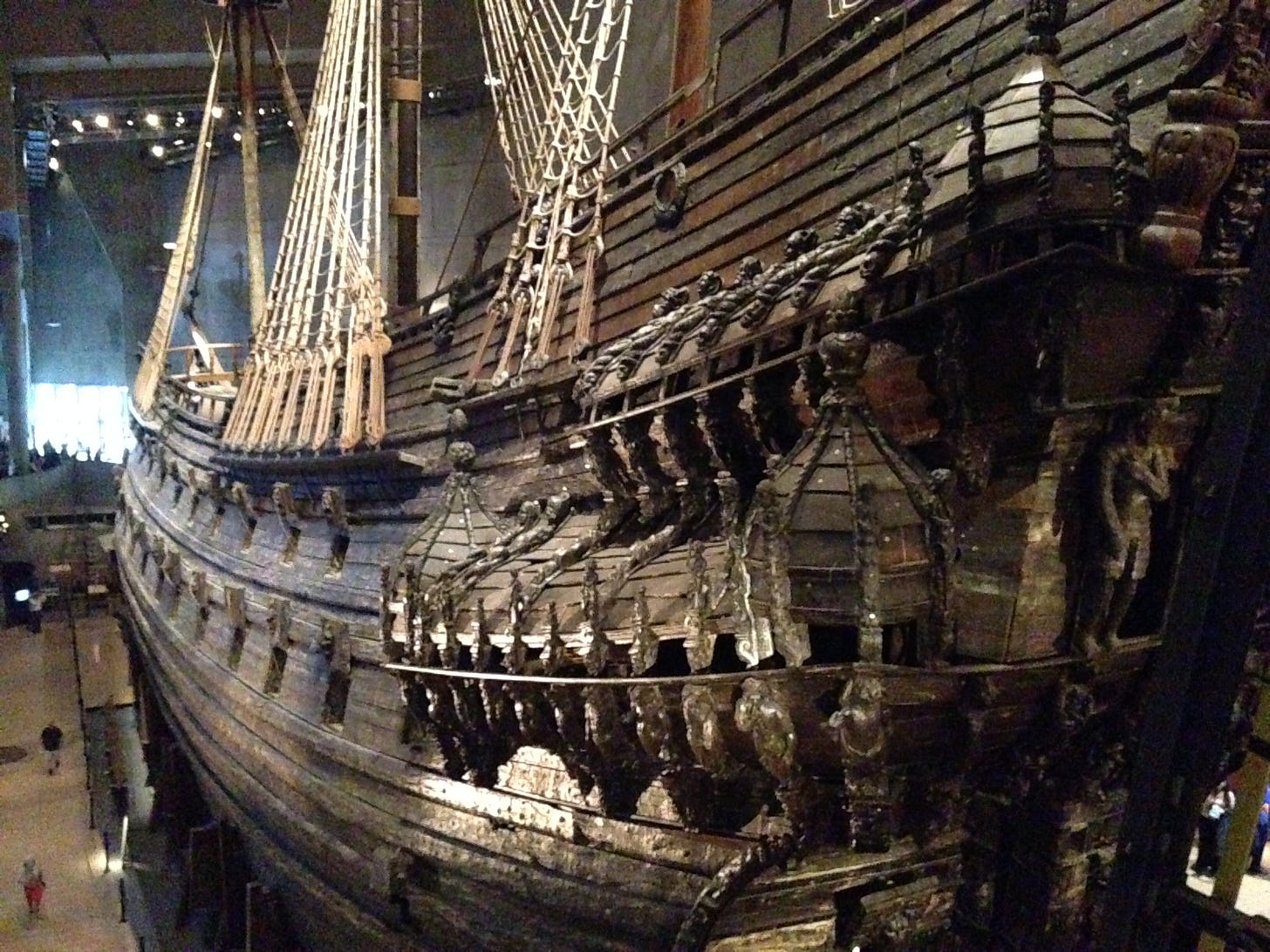

Last week I shared some stories about people we met on our family’s trip to Norway five years ago. This week I’d like to start with a story from the Vasa Museum in Stockholm.1 The Vasa, a seventeenth-century Swedish warship that sank off the coast of Stockholm, was dredged up in 1962 after a history buff persuaded the Swedish government to fund the project. The ship was painstakingly restored and put on display for the 1.5 million visitors from around the world who flock here every year.

To give you a sense of how huge the ship is, it took me thirty-five seconds to walk at a brisk pace from end to end, and the ship’s hull reaches up four stories to the ceiling of the museum. If the ship looks familiar, that’s because the art team from the Pirates of the Caribbean movies studied the Vasa when they were designing the Flying Dutchman ship for the second movie.

Despite its imposing appearance, the Vasa was in fact an ignominious failure. Originally intended to be the finest, most beautiful, and most heavily-armed warship in the world, its maiden voyage in front of the entire city of Stockholm lasted for only 25 minutes, at which point a gust of wind blew it over. All the cannon portholes were still open when the ship tipped over, because the crew had fired a celebratory burst from the 72 cannons. Even worse, the doors were blocked by the heavy cannons, so the crew couldn’t stop the water from rushing in. There was one piece of luck: the ship was so close to port that 170 of the 200 people onboard were saved, including all the children and nearly all the women. (Crew members had been allowed to bring their family members on the maiden voyage.)

So why did the Vasa sink at the first gust of wind? The Vasa was built to a design from King Gustavus Adolphus, who, needless to say, was not a professional ship-designer. To accord with the king’s grandiose vision, the Vasa was much taller than usual, with not one but two levels for cannons (which are heavy), and because the king wanted the ship to be fast and maneuverable, it was narrower than battleships were supposed to be. It seems so obvious that the ship would be a disaster when we look at it now—why didn't someone see the problem and warn everybody? Well, there are two reasons:

1. The ship was built by the Dutch, the best shipbuilders in the world. The Dutch didn’t use plans but instead relied on the expertise of earlier builders. Usually this worked great, but the king’s modifications to the typical ship—extra-tall, top-heavy, and narrow—had never been seen before, so the experts had no knowledge or experience relevant to the king’s design.

2. The ship’s captain in fact did realize that the ship would be a disaster and even conducted experiments to demonstrate the ship’s instability to the admiral (he had the sailors run back and forth across the deck to show how badly it swayed). The admiral saw the problem too, but, fearing a violent reprisal, neither man dared tell the notoriously volatile king.

So the ship sank, thirty people died, and the Swedish economy, while not crippled, was stalled for years. The moral? Systems where authority is so respected that people are afraid to speak up—and, even if they did speak up, those in power refuse to listen—lead to suffering, failure, death, and disaster.

Three current examples

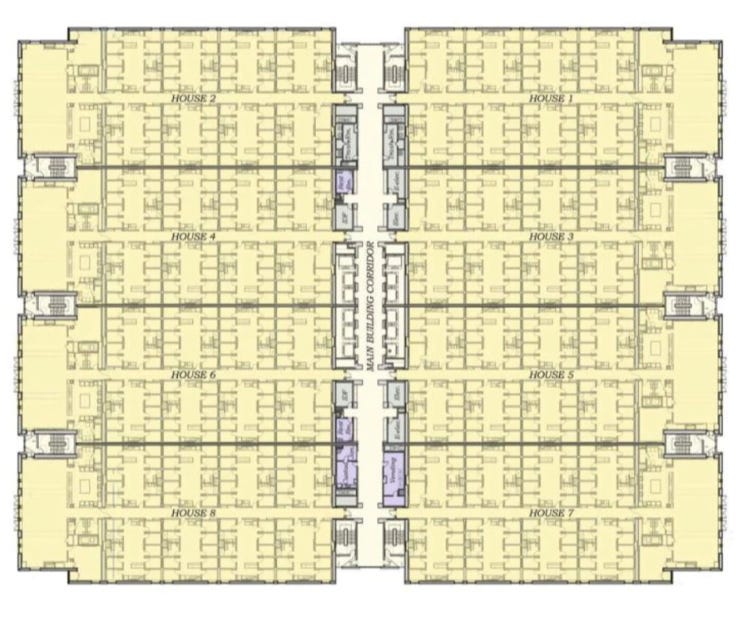

Three stories in the news during the last couple of weeks feature rich and powerful people who, like King Gustavus Adolphus, lack expertise and yet presume to dictate to others, with potentially deadly consequences. Many readers may be familiar with the story of Charles Munger, the 97-year-old billionaire who, absent any formal training, fancies himself an architect. He has donated $200 million to the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) for the construction of a new dorm, but under the condition that his plans be followed exactly. The monstrosity he designed—a dorm to house 4500 students, only 6 percent of whom would have windows—is so inhumane that the architect in charge resigned in protest. Were the building to be constructed according to Munger’s plan, it would be the eighth densest city in the world, just behind Dhaka, Bangladesh. I took one look at the proposed plan and immediately thought of an additional problem that should be apparent to anyone not blinded by a lifetime as a billionaire whom no one dares criticize. See if you can figure out what I noticed:

Those tiny cubicles are individual dorm rooms. The entire building has only two main exits.2 What if there is a fire? Or a carbon monoxide leak? Or some other event that provokes a stampede? How will the students get out safely without being trampled? How many of them would have to die because the UCSB development office is so eager for Munger’s money that no one will tell him his design is dangerous?

I have always been a huge fan of Alec Baldwin, especially his portrayal of Jack Donaghy in 30 Rock. So it gives me no pleasure to number him among the King Gustavus Adolphus-types who are so rich and powerful that they stop listening to the advice of experts. I initially pitied Baldwin when I heard the terrible news last month that he shot and killed a camerawoman and shot and injured the director of his new movie, Rust. How could he have known that the gun was loaded,3 especially when crew members said it was safe? I thought to myself.

But then I learned that six union crew members had repeatedly tried to alert the producers to dangerous conditions on the set—standard procedures for the safe handling of guns were not being followed, and the week before the fatal shooting, two prop guns accidentally discharged live rounds. The workers did the right thing and spoke up, but they were ignored. In fact, one of the producers ordered them off the set and threatened to call security if they didn’t go voluntarily. Alec Baldwin the actor is not responsible for firing the gun that he had been told was safe, but Alec Baldwin the producer was indeed responsible for an unsafe workplace, as were all the people in charge of the conditions on set, especially when employees who were weapons experts had warned them.

Last week we saw yet another example of a rich and powerful person who ignored safety concerns raised by those on the ground (literally in this case) and who as a result contributed to the deaths of eight people and the injuries of hundreds. During the disaster at Astroworld, people on the ground right below Travis Scott begged him to stop performing so that ambulances could get through and so that people could get out, but he continued to play for forty minutes after officials had deemed his concert a “mass casualty event.” Even if we were inclined to give Scott the benefit of the doubt, we should remember that he has a history of urging fans to incite mayhem at his concerts. Power insulates the powerful from seeing the rest of us as individuals whose lives are equally valuable to theirs—and when we have relevant experience and knowledge, power insulates the powerful from our voices.

Checklists and learning from mistakes

We have seen that powerful but ignorant people can wreak a lot of havoc. But what about when the person in authority is an expert but is still wrong? How can we regular people get around the hierarchy and ensure that the person in authority listens to our concerns?

I’d like to share another story. About forty-five years ago, a boy in my class needed knee surgery. When Darin returned to class, he was not on crutches as we had expected but was instead in a wheelchair. His mom told the teacher that the first thing he said when he came out of anesthesia was “Why do both my knees hurt?” Yes, you guessed right. The surgeon—in spite of working at one of the top research hospitals in the country—had opened up the wrong knee, and a little boy had to endure additional pain and immobility because of his mistake.

This kind of thing doesn’t happen anymore. When a patient goes in for knee surgery nowadays, the nurse will ask him or her to point to the knee that will be operated on, and s/he then takes out a permanent marker and draws a big circle on the correct knee and an X over the wrong one. This procedure may seem excessive until you remember Darin and his surgeon’s mistake. To their immense credit, doctors and healthcare authorities are working to eradicate or at least lessen the frequency of medical errors, which still cause tens of thousands4 of injuries and deaths every year.

Three tools in healthcare offset the danger that powerful people will charge ahead without listening to feedback. The first is the checklist. As Atul Gawande has discussed in his excellent book The Checklist Manifesto, doctors and hospitals have taken their cue from pilots’ checklists and now systematize many procedures in healthcare. The checklists protect patients not only from mistakes but also from quackery or exploitation; doctors, nurses, and other knowledgable people write the checklists rather than, say, Gwyneth Paltrow or Martin Shkreli. The checklist circumvents the usual hospital hierarchy: nurses or residents who notice something wrong don’t have to worry that they lack the authority to speak up. The checklist puts everyone on the same footing so that everyone checks, for example, that medications are the correct dose, that the correct devices are laid out on the surgical tray, or, to return to poor Darin, that the incision is in the correct knee. There are also checklists for cleaning hospital rooms, controlling the spread of infection, and performing many other routine tasks. This article includes ten sample checklists for readers who are interested.

At least in the US, the days of the God-like doctor who wields absolute, unquestioned authority are thankfully long gone.5 Doctors follow the scientific method and change their conclusions when the evidence shows that a treatment isn’t working or causes more problems than it solves. This can feel frustrating to patients: Why do doctors keep changing their minds? we sometimes wonder. But in fact medical professionals are correct to stop recommending treatments when they discover they’re harmful—for example, the routine administration of aspirin to people over sixty or a low-fat, high-carb diet (as an inveterate lover of butter and cheese, I am happy to tell you that we now know that low-fat, high-carb diets are bad for us). As with the checklist, this focus on the evidence takes the issue outside of the hierarchy and systems of power: the evidence is what matters, not the status of the person making medical recommendations.

Doctors’ training reinforces this willingness to learn from new information; since 1983 all accredited medical residency programs must include morbidity and mortality conferences. In these conferences, doctors talk honestly about mistakes so that others can learn from them. Crucially, the conferences are confidential, and speakers are not blamed because they made an error but rather appreciated because they are helping others not to repeat them. These conferences flip the power hierarchy: senior doctors demonstrate publicly that they are not perfect and will in fact thank their junior colleagues for catching their mistakes. And when new residents hear a senior doctor talking about his or her mistakes, they internalize the message that mistakes happen, and that it’s important to speak about them openly.

Let’s return to the Vasa

As it turns out, the Swedes were more like doctors than like billionaire would-be architects. The seventeenth-century Swedes learned from their mistake: the Vasa had a sister ship, which was in the process of being built when the Vasa sank. The builder, aware of the Vasa catastrophe, made the sister ship one meter wider, and that ship had a successful thirty years at sea. And present-day Swedes demonstrate through the Vasa Museum that they know how to learn from mistakes of the past. Although our guide said some Swedes don’t like having such a colossal failure displayed to the millions—in his words, “They say, ‘If people think we’re such terrible engineers, who will buy our IKEA?’”—it’s undeniable that the failure has become a success: the Vasa Museum is the number-one tourist attraction in Sweden and also has allowed scientists and historians to learn an extraordinary amount about life and art in the early seventeenth century.

Sometimes the only way to get the powerful to listen is to shake them up through a public catastrophe, as with the failure of the Vasa or the senseless deaths on the Rust movie set or at Astroworld. Sometimes people can find a way around the hierarchy, as with a checklist or a focus on evidence. But best of all is when the culture changes so that even powerful people value the insights and contributions of the rest of us. It’s a worthy goal for us in our daily lives too—to speak up when we see a problem but also to listen to other people and to consider that we might be wrong.

How about you, readers? Have you experienced a situation where someone in authority was about to make a big mistake, and you or someone else spoke up? Or where people were too afraid to speak up? What happened? Please share your stories in the comments!

The Tidbit

There are a lot of cartoons about IKEA online. This was my favorite, possibly because I have been this mom more than once:

All the information about the Vasa is taken from our excellent tour guide. The Vasa Museum allows its guides to research and write their own scripts, so the tours are particularly interesting and informative.

Officials from UCSB, in a statement, have said that there would be fourteen additional exits in addition to the two main ones. However, even sixteen exits on the ground floor won’t solve the problem of how the students on the upper floors could escape.

This is leaving aside the question of why movies need to use real guns or, for that matter, why we make so many movies featuring guns in the first place.

The oft-cited statistic that medical error is the third-leading cause of accidental death is almost certainly wrong, and the usual figure of 250,000 deaths per year from medical error is likely greatly inflated. But even at lower numbers, medical error is still a problem that doctors are commendably addressing.

I was surprised to discover that this culture lingers in the Czech Republic. When I needed a routine injection back in 2017, a doctor insisted I receive it as an in-patient. This seemed insane to me: these injections are normally given on an out-patient basis in most other countries, including the US. When I objected to being hospitalized for no reason, she was so angry at me and Matt for daring to talk back to her! Luckily, we were able to find a more senior doctor to overrule her—exploiting the hierarchy for my benefit.

Powerful writing as usual. Thanks, Mari. Your spot-on epistle made me recall the movie, from which I have only one dim recollection. Steve Martin, I think, is an advertising executive in charge of the Volvo account, and his current campaign is, "Volvos: they're boxy but good".

On the serious side, I recently worked for a dull, mean, greedy egomaniac. I'll cite one example among dozens that I experienced: We had to change into food production gear upon entering the production area, then change back when returning for breaks, etc. There were about 30 human beings changing concurrently. The changing room was 16 feet by 16 feet. So needless to say, all through the pandemic, we packed in there, admittedly masked, and shared our bugs. There were two sizes of smocks, which were mixed helter skelter, adding to the time required as we sorted through smocks to find the right size. That added a little totally unnecessary time to the process, since the smocks arrive sorted, but in bundles of a dozen. The bundles were all mixed up.

I went in to Brett's office to discuss the pandemic and offer a couple of suggestions regarding employee pandemic health. When I brought up the unbelievably simple act of sizing the smocks on the racks, his demeanor of crossed arms and a frown immediately became friendly. He grabbed a legal pad, flipped a couple of pages, and displayed to me a whole page of this thoughts on this issue. He proudly announced that in the near future the smocks would be sorted. He was quite proud of this. Anybody with an IQ above about 87 would have spent 5 minutes on this with a phone call to the launderer. And then gone on to the dozens of other pandemic related actions that should have been taken.

Anyhow, your thoughts hit home. Keep up the good work, my international writer dudette friend!

Having visited the Vasa, I loved hearing all about it again. I had forgotten so many details.

Thank you, Mari, for your insights. I learn so much from you. …Ever the teacher.