Note: I wrote this post a couple of weeks ago, before the horrific mass shootings in Buffalo and Texas, which have robbed the world of thirty-one beautiful human lives. If you live in a state that has Republican senators, I urge you to call them and say you want them to vote yes on HB8, a bill passed by the House in 2019, which would require universal background checks, including for gun sales that occur at gun shows, over the internet, and between private parties. Not a single Republican senator supports this bill, even though universal background checks are supported by 90 percent of Americans. We do not need to agree to an irresponsible regime of violence and slaughter that is imposed on us by a tiny minority. Thank you for listening, and now on to the essay.

I recently visited the Zentrum Paul Klee to enjoy a retrospective exhibition of the career of Gabriele Münter. Münter (1877-1962) was Kandinsky’s partner, a friend and colleague of Klee, and an active member of the Blue Rider group.1 The exhibition featured a few hundred works in all—paintings, photographs, embroidery, drawings, and (charmingly) two pictures by Münter’s niece and nephew, which Münter reimagined and incorporated into some of her own work.

Part 1: Gabriele Münter

One of the goals of the exhibition was to make the case that Münter, likely because she was a woman, has been undervalued by art historians and actually belongs in the first rank of modern painters. I came away from the exhibition with conflicting feelings. On the one hand, I loved Münter’s works and thought they were accomplished, vivid, striking, and varied. On the other, I was surprised by how varied the works were, and not always in a good way. Unlike most great painters, Münter doesn’t seem to have a consistent style that would allow an observer to look at a painting and say, “Yup, that’s a Münter.” In fact, many of her pieces mimic the style of other artists of her time. Some of her portraits looked like they could be by Egon Schiele, one still life features apples straight out of Manet, and a couple of her paintings remind me of Klee. And yet a few of her paintings give us a glimpse of her unique style and vision, which left me wishing she had felt free to paint in her own way more often.

For the remainder of the first part of this essay, I will share a few of Münter’s pieces that I especially liked—and one that I disliked, for reasons that will soon be clear. See if you agree with me that her career shows a tension between expressing her own style and adopting the styles of her colleagues.

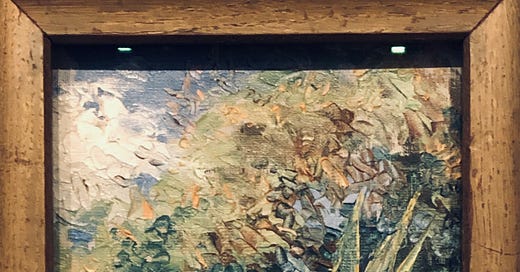

Münter painted “Aloe” while on a visit to Tunisia. It is tiny—midway between a postcard and an A4 sheet of paper. The paint is extremely thick and layered, and the painting reminds me a bit of Monet’s waterlilies.

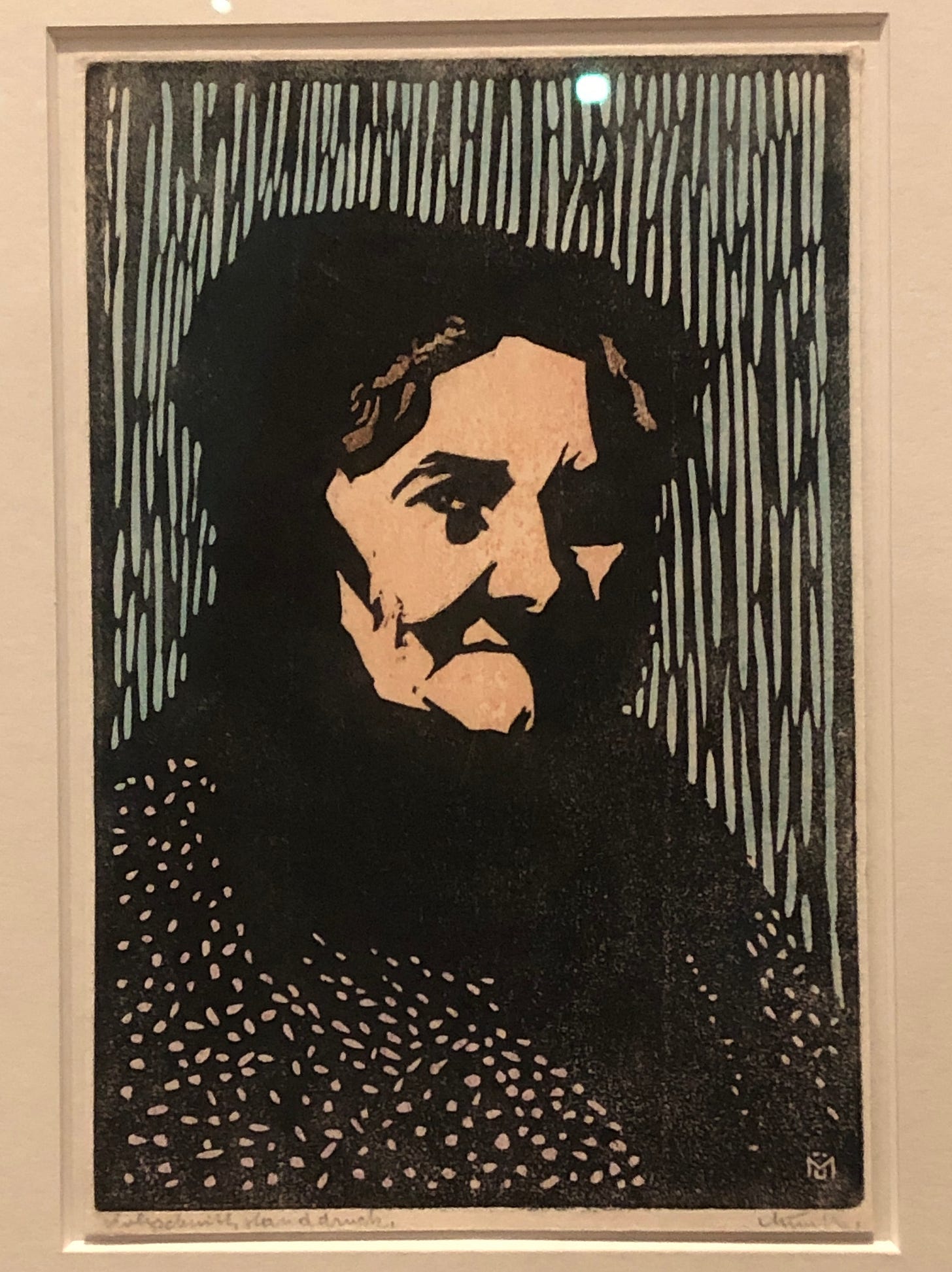

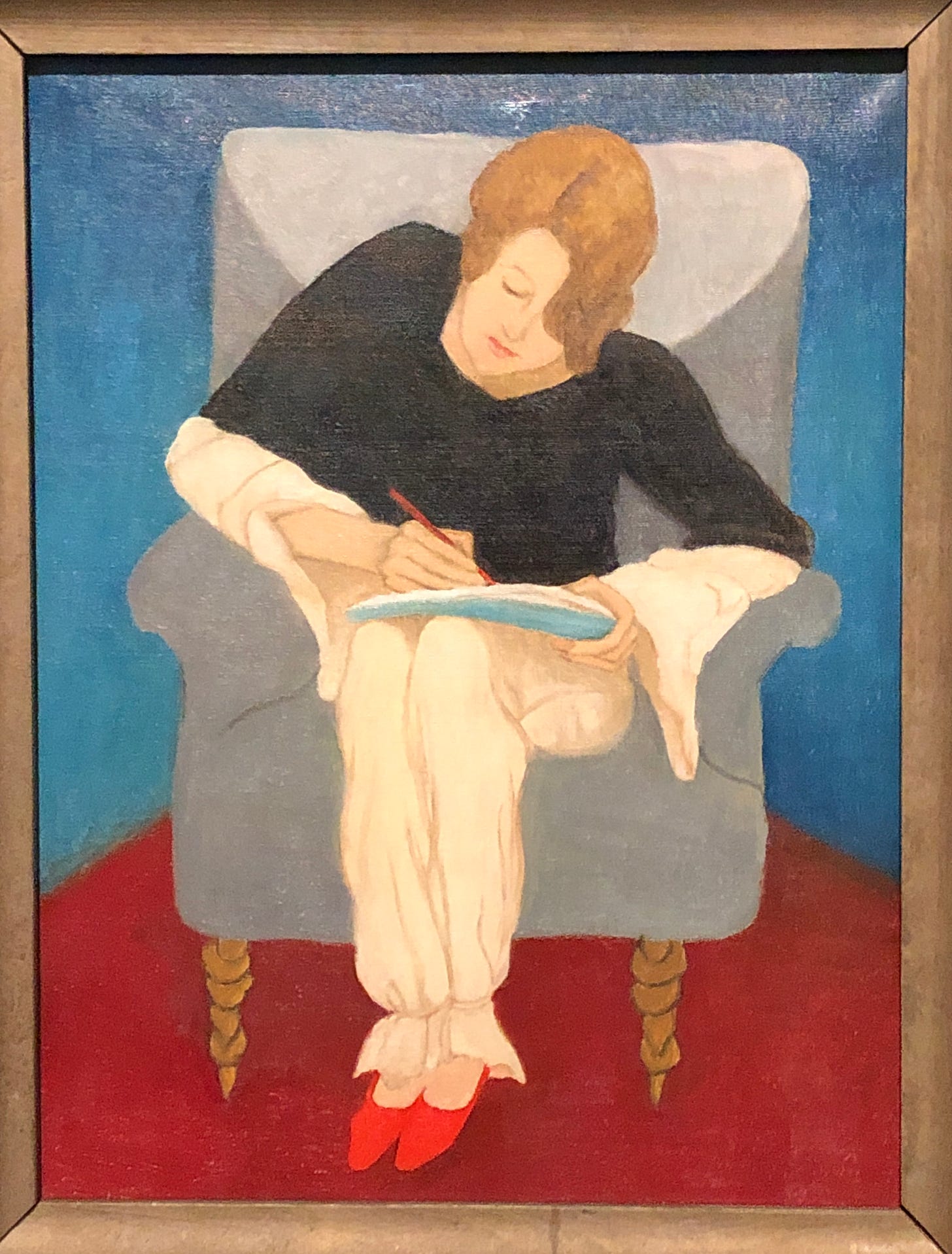

Next, take a look at three portraits of women, two from early in Münter’s career, and one from her mature period. In all, Münter created 250 portraits, 80 percent of which were of women.

Münter and other members of the Blue Rider group were inspired to learn the linocut technique after nineteenth-century Japanese woodcuts were exhibited in France. I think Mme. Robert’s expression here is mischievous and playful, which makes a nice contrast with the heavy vertical lines.

I find the expression of grief on the woman’s face to be so arresting. Look at how the background and her eyes are the same shade of blue; it is as though she is projecting her emotions into the world around her.

This portrait is done in what I think of as Münter’s own, unique style. It is representational rather than abstract and is characterized by clean lines with almost no shading. Notice how the diagonal lines from all four corners converge on the woman, drawing our eyes in and literally centering her. And yet she ignores our gaze and instead carries on with her writing. Good for her!

Münter painted several expressionistic landscapes like this one. Her bold, contrasting colors and strong lines remind me of Franz Marc and Kandinsky.

Now compare two still lifes, the first from Münter’s early career, and the second from her artistic maturity. (Sorry about the bad photo of the first picture. It was difficult to avoid reflections in that particular gallery.)

This is a quite large painting, whose size, marked outlines, and the vivid contrasts between turquoise and red grab our eye. Münter uses a spontaneous, primitive style here in her painting of souvenirs she had brought back from Tunisia.

I love this tiny and intimate painting. As with “Lady in an Armchair, Writing,” here too Münter uses energetic diagonals to draw our gaze to the center of this peaceful domestic scene. She dashed off this painting when, in her own words, “While the table was being cleared, I suddenly saw a still life, was moved, and painted.”

In 1935, a road was being built near Munich in preparation for the 1936 Olympics. Münter painted a series of works that documented the construction of the road. She rejected the expressionistic style of the Blue Rider group and chose instead to paint in the plain, realistic style favored by the Nazis. In 1936, “she contributed her paintings of construction sites to the propaganda exhibition Adolf Hitler’s Streets in Art.” Unlike Klee, Kandinsky, and other artists in her circle who left Nazi Germany, Münter remained in Germany while the Nazis were in power, and she allowed them to use her paintings as propaganda. Because she took an “adaptationist” attitude, she was allowed to have “rationed canvases, brushes, and paint during the war.” At the same time, though, she hid paintings by her friends that the Nazis had denounced as “degenerate art.” It is thanks to her courageous rescue of those works that we still have several masterpieces that the Nazis had wanted to destroy. We need to think humbly about what we would have done in Münter’s place; I am not sure we all would have been heroes. Isn’t it more likely that we too would have found ways to compromise and get along, as Münter did?

Part 2: Leda and the Problem with Being Agreeable

I am not an art historian, and until I saw this exhibition, I had never heard of Münter, so I’m just speculating here, but it is possible that one explanation for both Münter’s tendency to imitate other painters2 and her willingness to work under the Nazi regime is that she may have been extremely agreeable. “Agreeable” here is a technical term. In psychological theory, agreeableness is one of the Big Five personality traits (the others are openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, and neuroticism; the acronym is OCEAN). As the linked Wikipedia article puts it,

Agreeable individuals value getting along with others. They are generally considerate, kind, generous, trusting and trustworthy, helpful, and willing to compromise their interests with others. Agreeable people also have an optimistic view of human nature.

How on earth could anyone see a problem with being agreeable? Most workplaces require people to work together, and agreeable people make teamwork smoother and more effective. It’s just pleasant to be around agreeable people. And I sympathize with this attitude for a personal reason: As you may have guessed from earlier Happy Wanderer essays, I score off the charts in agreeableness. I can’t stand conflict, I can’t bear to hear negative comments about anyone, I try to avoid criticizing people if at all possible, and I am always looking for common ground and compromise. As a friend once asked me in mock-exasperation, “Is there anyone you DON’T get along with?!” And the answer is, pretty much no.

However, because I am not only agreeable but also self-critical, I recognize that there are problems with always trying to make everything so harmonious. Maybe I am biased by my love of twentieth-century classical music, but some dissonances shouldn’t be harmonized.

Sometimes conflicts shouldn’t be smoothed over but should instead play out, sometimes what we need is not compromise but sticking up for our principles, sometimes criticism is warranted, sometimes we ought to be pessimistic, and sometimes we need to say “I don’t agree with this!” After all, we only progress when we acknowledge and learn from our mistakes and from each other. As psychologist Adam Grant put it in a recent interview,

There’s a flavor of conflict that can be constructive if it’s managed well, which is task conflict. . . . It’s where we disagree on ideas and visions and strategies and decisions. If two people never disagree, it means that at least one of them is not thinking critically or speaking candidly. . . . Great minds do not think alike. They challenge each other to think differently.

Being agreeable can hurt the agreeable person too. Agreeable people often subsume their needs to those of others, which can lead to resentment and dishonesty in their relationships. I was struck by this theme when I watched The Lost Daughter, a film directed by Maggie Gyllenhaal and based on a novel by Elena Ferrante. (Warning: spoilers ahead.) To me the most shocking scene in the film happens near the beginning, when present-day Leda (played by Olivia Colman) is sunning herself in the middle of an empty beach. A large family arrives and asks Leda to move, and she refuses, without offering any excuses or explanations. The family remonstrates with her and even gets angry at her refusal, but she remains steadfast. Leda’s refusal is a striking violation of the social norm that women ought to agree to other people’s requests. We could even call Leda a Karen. The young men in the family are outraged and retaliate against her throughout the film to punish her for violating the agreeableness norm. At one time or another, we have all been asked to make room, move over, give something up, or otherwise inconvenience ourselves to accommodate others, and the more agreeable we are, the more we agree.3 So I admit that I got a kick out of seeing Leda refuse to budge—until later in the film, that is.

In fact Leda learned to speak up for herself too late, and her earlier agreeable nature contributed to the destruction of her family. The scenes of young Leda (played by Jessie Buckley) are agonizing to watch. Leda works full-time, just as her husband does, but she is totally responsible for all the housework and childcare. She doesn’t confront her husband though, or even politely insist that he do his share. Instead, she seethes, feels helpless, and begins an affair with a man who flatters her. Even worse, she doesn’t set boundaries for her two young daughters, who are constantly interrupting her and hanging on her body when she is trying to work. One daughter even hits her. I kept wanting to tell Leda, “You’re allowed to say no to your children, especially when they hit you!” Leda’s passivity and avoidance of conflict prevent her daughters from learning the proper way to treat other people. Leda is so reluctant to assert herself and draw boundaries that she believes the only way she can carve out a place for herself is to abandon her daughters entirely. Even though this is obviously a movie, it contains truths about our lives. We don’t always have to be agreeable; our families, workplaces, and society as a whole will be better off if we speak up for ourselves and for what is right—and we will be too.

What do you think, readers? What are the virtues and potential downsides of being agreeable in your lives? And did you enjoy Münter’s paintings? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

By now most readers know about what is possibly the most thrilling thirty seconds in the history of sports. Rich Strike was given 80 to 1 odds and was only put into the Kentucky Derby the day before the race. He had the worst opening position, at the far outside, and his jockey, Sonny Leon, had never ridden in the Kentucky Derby before. For most of the race they were near the back, and it was only in the final seconds that Leon showed his strategic brilliance and guts, and Rich Strike unleashed his speed and power. Even if you’ve seen the race already, this overhead view, with arrows pointing to Rich Strike and Epicenter (the favorite) is a revelation. We all love a story of an underdog everyone has underestimated who triumphs against the odds (literally in this case). Or at least I find this race inspiring and have watched it multiple times. I hope you will enjoy it too!

While the impressions and reactions I discuss are my own, all the facts and quotations in this essay come from the exhibition guide, Gabriele Münter: Pioneer of Modern Art. Unfortunately, no author is listed, so I can’t give her credit for the helpful information she provided.

Another explanation for her chameleon-like ability to paint in the style of other artists, though, is that women weren’t allowed to attend art school back then, and so Münter had to learn by imitating her colleagues.

My husband’s reaction to this scene was quite different from mine. He commented that he would have moved to accommodate the family. And it’s true—he would absolutely have moved over for the family, because he is a considerate person. But I suspect that the family wouldn’t have asked a man to move in the first place.

I loved the horse race, the movie “The Lost Daughter” (although I was so frustrated by that main character!), and your discussion and sharing of those paintings. It is interesting how she is so talented and her paintings are so varied (instead of having, as you mentioned, a recognizable style of her own).

So excited to see you mentioning the Big 5 and talking about agreeableness. There is a dark side to every trait, and overplaying anything (as you have so aptly demonstrated) can have negative consequences for oneself and/or others --- even something as innocuous-sounding as "agreeableness." You might like this brief chat by Linda Hill from Harvard talking about creative abrasion... https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hDKJTOhtYiQ