This is the second of two posts about our recent trip to Madrid. You can read last week’s post, To Thine Own Self Be True, here.

As an inveterate lover of dogs, I was delighted to discover that Madrid is a wonderfully dog-friendly city. Take this glamorous lady and her short-stuff sidekick:

Then there was Julia, a copper-colored Pharaoh Hound we met in Plaza Mayor. She rolled over on her back for belly rubs and refused to leave with her human. “She’s being dramatic,” he remarked. “She doesn’t want to go where I want.” Best of all was the plump Cocker Spaniel who wove in and out of the line at the Prado—and then plunged his head into the knapsack of the guy behind me to steal a few bites of his sandwich. We all laughed, even the guy whose sandwich it was.

But I digress. This post is actually about art we saw in Madrid with Alex, our excellent guide at the Prado.1

What Makes Art Priceless?

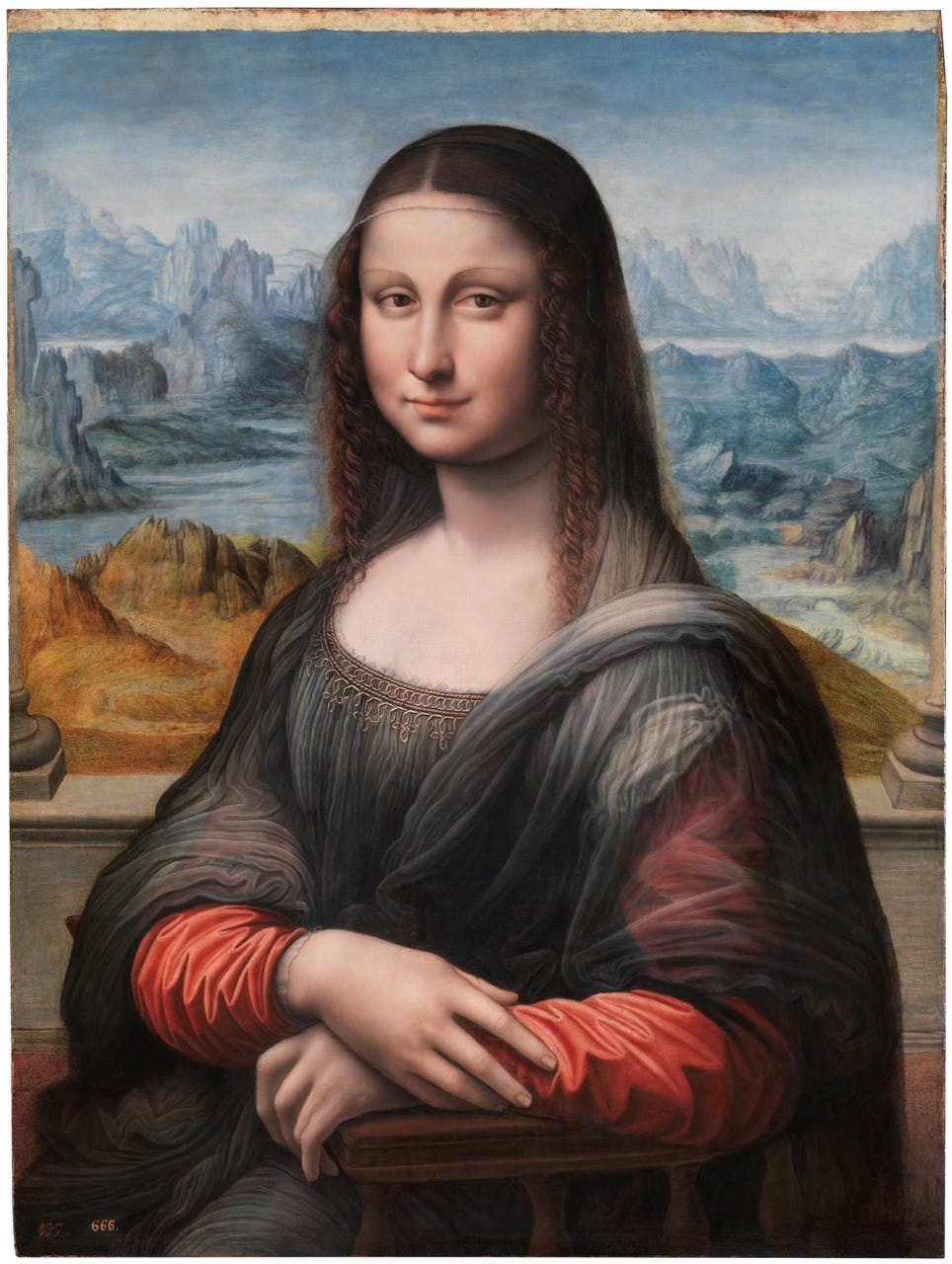

Did you know that there is another Mona Lisa, in Madrid?

The Prado Mona Lisa, unlike her Parisian twin, presides over a totally empty gallery, so we were able to get up close and study her. I discovered that I actually preferred her to the “real” one. The background is brighter and cheerier than the grayish-brown background in the Paris version, and I liked the hint of personality in her vivid red sleeves peeking from her black gown. The Prado’s website makes the case that this painting is no cheap knock-off, and that Leonardo had a major role in its creation:

[It] was painted by one of Leonardo’s pupils. The fact that each pentimento, or change, in Leonardo’s original (to the bust, outline of the veil and position of the fingers) is repeated here suggests that the two works were created simultaneously.

. . .

Only someone working alongside the master would have witnessed the adjustments that he made to the work in progress.

Why do we revere original works—booking our pilgrimages to them months in advance, waiting in endless lines, and pushing through crowds for a quick glimpse—but we (literally) discount the copy? The Marxist critic Walter Benjamin argues that an original work possesses an “aura” arising from “its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” In Benjamin’s view, our reverence for original art hearkens back to art’s role in ancient religions, when artistic works were objects of worship.

But according to Alex, this theory doesn’t apply to Renaissance Europe. Painters’ workshops back then were businesses that routinely made and sold copies of famous works. The artists believed that originals and copies were of equivalent value. And as a result, noble patrons thought of even great artists as akin to basket weavers—artisans producing useful objects.

Practical Genuises

Artists of this era, far from being rarefied elites, had to get down in the dirt with ordinary folks in order to create their works. Many of them consorted with prostitutes, who served as their models. (A priest once castigated Caravaggio for using a notorious prostitute as his model for a religious painting. Caravaggio responded, “How do you know her?”) And like doctors at this time, artists sometimes engaged in grave-robbery. The horses in many paintings by Diego Velázquez are puffy-looking, perhaps because the horse cadavers he used as models were starting to go off.

Other artistic developments that we normally ascribe to genius are often actually just signs of improved technology. For example, compare the two paintings below, by Pieter Breugel the Elder, which hang side-by-side in the Prado:

Notice how the first painting is blurry and faded. It lacks detail, especially when compared with the brilliance and clarity of the second painting. This is not because Breugel got better, but because paint did. Artists in Breugel’s time made their pigments from egg yolk. But egg yolk dries so quickly that painters couldn’t paint in fine detail. During Breugel’s time, Flemish painters discovered how to use vegetable oil as a base. Because oil dries slowly, painters were able to include much greater detail and to layer colors to create depth. Over the next century, oil-painting technology spread throughout Europe and revolutionized art.2

Another artistic development was enabled by explorers, who created a demand for canvas sailcloth. Artists could opt to paint on newly-available canvas instead of wood panels. Canvas is lighter than wood, and sheets could be easily stitched together or cut to size, rolled up, and transported. It became possible to create paintings of various sizes, including extra-large. Canvas was also much cheaper than wood panels, so middle-class people could afford art. These new customers changed paintings’ subject matter; no longer did paintings have to depict noble patrons or religious themes. In addition, while the Church demanded that saints and other religious figures be portrayed as generic types, ordinary people wanted to see themselves in the works. These new customers incentivized greater realism in European art.

Art Tells the Truth

In 1814, the Spanish government commissioned Goya to paint works commemorating the expulsion of Napoleon’s army from Spain, but instead Goya created what are arguably the world’s first anti-war paintings. The Second of May 1808 shows not a glorious victory but a chaotic slaughter. Daggers stab, scythes slice, blood flows, hooves trample. Even the horses are terrified.

Goya completed a second painting, The Third of May 1808, two months later. The painting depicts the morning after the uprising, when the French executed hundreds of people. “The colorless firing squad—a faceless machine of death—mows them down, and they fall in bloody, tangled heaps. Goya throws a harsh prison-yard floodlight on the main victim, who spreads his arms Christ-like to ask, ‘Why?’”3 Goya was honest about the brutality of war, which victimizes everyone regardless of which side they’re on.

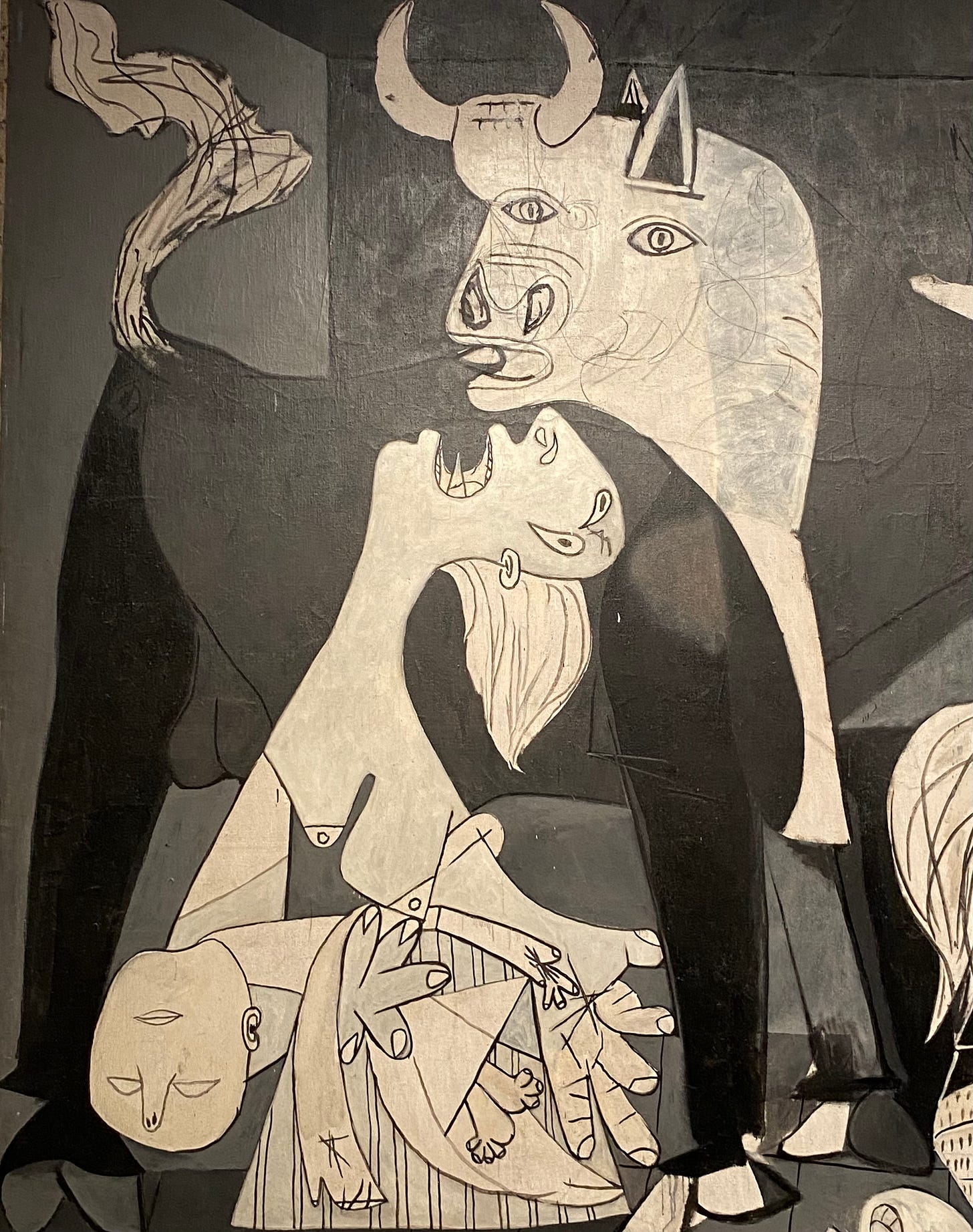

Even more devastating is Picasso’s greatest work, Guernica. In 1937, Picasso was just beginning a patriotic painting that had been commissioned by Spain’s Republican government. Then the fascist general Francisco Franco invited Hitler to “use [Guernica] as a guinea pig to try out Germany’s new air force.”4 The German bombs murdered hundreds of civilians and leveled the town. Picasso threw out his previous plan and started working on his artistic testimony to the atrocity. He chose to paint in black and white and to focus on the bombing’s victims, especially the bereaved mothers, whom he shows have been deformed and shattered by their loss.

Picasso lived in self-imposed exile for the rest of his life. Guernica was originally exhibited in Paris and only came to Spain in 1981, after Franco’s death. Similarly, while Goya was not prosecuted for creating his anti-war paintings, he was driven into exile. And yet in spite of rulers’ efforts to punish artists and to suppress their work, hundreds of thousands of people now visit these paintings every year to bear witness to the horrors of war. As Elvis tells us, “Truth is like the sun. You can shut it out for a time, but it ain’t goin’ away.”

Dogs Keep It Real

Let’s lighten the mood and return to dogs, this time in a painting I saw at the El Greco Museum in Toledo:

Is there anyone who isn’t immediately drawn to the perky little dog? Never mind Jesus, the disciples, and the Last Supper—there are treats to be had! I love how the artist captures the dog’s distracting but adorable appetite. When I was a kid, our family had a basset hound who could tripod just like this dog. His stubby hind legs poked frontwards, and his sturdy tail propped him from the rear. We would be eating dinner, and suddenly, at the edge of the table, a small brown head would appear, as he posed fetchingly, hoping we would toss him a scrap. Tristán’s painting forces us to admit that we fallen beings are more like Judas than we might have thought.5 We turn from holiness and higher things to indulge the humble, beloved critter at our feet.

How about you, readers? What are your ideas and questions about art? Or dogs? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

The most famous painting in the Prado is Las Meninas, by Velázquez. Alex noted that there is a puzzle in the painting. The king and queen are visible in the mirror in the center. Who are they looking at? At themselves in the mirror? Or us? Velázquez, on the far left, appears to be looking right at us. If you follow the eye-lines in the painting, it seems as though Velázquez is including us in the royal portrait, next to the king and queen.

Could be! But I find the novelist Samantha Harvey’s interpretation more inspiring. Who wants to pose stiffly with distant, miserable nobility? We are animals, after all, and even at the risk of fleas, it’s more fun to lie down with dogs.

The subject of the painting is the dog.

. . . It has its eyes closed. In a painting that’s all about looking and seeing, it’s the only living thing in the scene that isn’t looking anywhere, at anyone or anything. He sees how large and handsome it is, and how prominent—and though it’s dozing there’s nothing slumped or dumb in that doze. Its paws are outstretched, its head erect and proud.

. . .

An animal surrounded by the strangeness of humans, all their odd cuffs and ruffles and silks and posturing, the mirrors and angles and viewpoints; all the ways they’ve tried not to be animals and how comical this is, when he looks at it now. And how the dog is the only thing in the painting that isn’t slightly laughable or trapped within a matrix of vanities. The only thing in the painting that could be called vaguely free.6

Unless otherwise noted, Alex is the source for the information in this post. If you are headed to Madrid, I highly recommend his tour, which you can book here.

Another fascinating hypothesis about a technological revolution in art is the Hockney-Falco thesis. David Hockney argues that artists such as Vermeer were able to create remarkably clear, almost photo-realistic, paintings because they projected images on their canvases with a curved mirror or a camera obscura.

Rick Steves, Snapshot Madrid and Toledo (Berkeley: Avalon Travel, 2022), p. 68.

This quote and all facts about Guernica are from ibid., pp. 74–76.

I’m pretty sure Judas is the guy on the left with the red hair and sack of money.

Samantha Harvey, Orbital (New York: Grove Atlantic, 2023), pp. 158, 159.

Lovely thoughts on art in Madrid, Mari. Since we were just in Madrid seeing many of these same paintings your comments were even more spot on and enjoyable than usual. I, too, was surprised by the Mona Lisa “copy” in the Prado with no one looking at it. It’s beautiful—quite the surprise, too, since when we saw it there was no one else even in the same room. We could drink it in in peaceful solitude.