Well, my MOST controversial opinion is that I prefer Matthew Macfadyen’s Mr. Darcy to Colin Firth’s.

But this video is just a ruse to lure you in to this post. I have learned from bitter experience that when I share my most controversial opinion, I encounter the kind of outrage that we normally reserve for pooper-scooper scofflaws, book-banners, picky eaters, and other icky Philistines and complacently ignorant types.

I will sidle up to my point with a story. I grew up in Minnesota, Land of 10,000 Lakes (although really it’s more like 12,000 lakes, but that number isn’t as catchy). Back when I was a kid, Minnesota had a law that every student had to pass a rigorous water-safety course in order to graduate from public high school. We had to be able to swim; perform the survival float; administer CPR and first aid to drowning victims; pass a boat-safety test; and demonstrate that, while treading water, we could take off our jeans and turn them into life vests through the nifty maneuver of flipping them over our heads to fill them with air and then tying the legs around our necks. Given how often Minnesotans go Up North to the Lake, it is smart to equip us to handle water emergencies. As far as I know, no other state requires such a comprehensive water-safety course for high school students.

Before we continue, I ask you to please read the whole essay before firing off a comment in protest. If you read to the end, you may find that I have addressed your concerns. Or, who knows? You might even find my arguments persuasive. Ready? Here goes!

Lingua Anglica

I have lived in Europe for almost ten years, and our family has visited, between us, almost forty countries for work, school, and pleasure. In every single place we have been, without exception, English is spoken, usually with humbling fluency.1 My husband has worked on international teams in several countries. The work language is always English. When we lived in Prague, we attended an open rehearsal of Collegium 1704, a Baroque chamber group. The musicians hailed from Czechia, Slovakia, Poland, Germany, Austria, and Croatia. They rehearsed in English. Here in Switzerland, I have attended a couple of receptions to celebrate Taiwan National Day. Guests include diplomats and their spouses (and hangers-on like me) from around the world. All the speeches are in English. I could provide additional examples, but perhaps you are getting the idea.

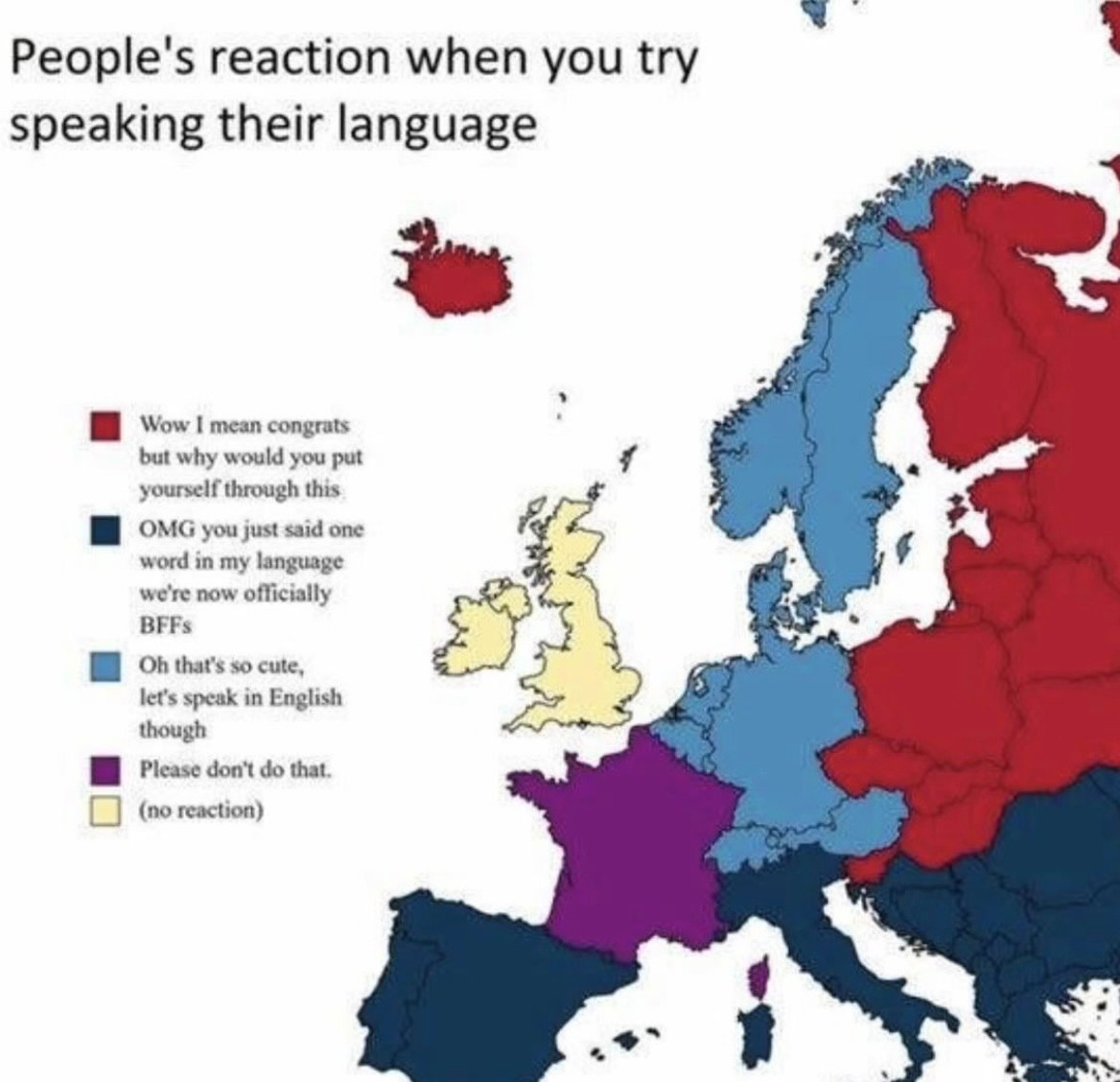

Or, if you’re still not convinced, take a look at this chart:

Sorry, French. You are no longer the lingua franca. It’s now English. Maybe we should just admit it and replace “lingua franca” with “lingua anglica.”

The sad reality is that public education is zero-sum: We don’t have infinite time in the school day to teach every imaginable subject. Ideally, we should spend our limited time teaching kids subjects that are useful for them—like water safety is for Minnesotans. Ok [takes deep breath]. Here is my most controversial opinion:

We should not require American high school and college students to take any foreign language classes.

A Digression about Shame

The vast majority of American kids will obtain little practical benefit from foreign language classes, so why are they required in so many schools? A clue can be found in the meme below, which I have seen posted self-righteously on Facebook.

We are embarrassed about our monolingualism and don’t want to be ugly Americans. Some of us have felt ashamed when we meet people from other countries who speak excellent English. We may think that speaking other languages is part of being well-rounded. Maybe we regret never learning another language. Or maybe we do speak another language and believe that the US would get more respect abroad if more Americans were like us.

We really ought to let go of our shame at being monolingual, though. Every country in the world has challenges, and so its citizens must learn skills to meet those challenges—skills that are unnecessary elsewhere. For example:

Cubans are famously good at maintaining very old cars. But it would be a waste of time and money to force students in non-Communist countries to take classes in car maintenance.

People who live in the extreme north of Norway have figured out how to cope with the “polar night” and have invented several techniques for avoiding depression during the dark winters. But it would make no sense to teach these techniques to children in sunny climes.

We Americans are good at battling insurance companies and health care bureaucracies. People in the rest of the developed world, who have universal healthcare, don’t need to learn how to do this.

Speaking English is a valuable job skill for people in other countries, which is one reason their students learn English. But native speakers of English2 don’t obtain similar advantages in the work world from learning another language.

American monolingualism is a pragmatic response to circumstances and as such is morally neutral; we Americans should be no more ashamed of being monolingual than a citizen of a desert country would be at not having bothered to take Minnesota’s water-safety course.

For English Speakers, Foreign Languages Are Like Knitting

Or painting, or oboe, or tennis, or chess, or any other intellectual pursuit that—if we invest the time and effort—enriches our lives. While foreign languages are rarely needed in the work world, they do enhance our understanding of other cultures and can lead to pleasant and even beautiful connections with other people. For example, because I speak the local language, German, in recent weeks I have reassured an older gentleman that the path through the woods wasn’t too slippery; condoled with an acquaintance over the death of her beloved dog; checked in with a neighbor about his upcoming back surgery; and joked with a fellow shopper about the store’s excessively large selection of bell peppers.3 Small, friendly encounters like these give meaning to our lives.

When we lived in Prague, my husband and I spoke Czech, which helped us befriend our neighbor Marta. Marta deputized her grandson to fix our many broken appliances, sent over homegrown cucumbers by the basketful, and baked us treats. When Marta’s husband was dying, I rode the bus with her to the hospital, and we held hands the whole way. So I understand from my own experience that knowing another language can lead to profound connections with other people.

But here’s the thing: There are all kinds of pursuits that can bring intellectual stimulation, meaning to our lives, and connections with other people. To be successful in any enterprise, students must have interest or talent, and preferably both. Not everyone is talented at or interested in learning languages, and some students would be better off spending their spare time on art, music, sports, chess, or, heck, knitting. Foreign language classes ought to be available as electives for kids who want to learn. But forcing all students to take these classes, as we do now, causes many of them to miss out on more appropriate opportunities.

Neither Necessary Nor Sufficient

In fact, foreign language classes in American high schools and colleges are neither necessary nor sufficient for learning a language. Let’s take the “sufficient” part first. High school and college classes are an ineffective way to teach languages. Typically, language classes meet two or three times a week for an hour or so and emphasize grammar and vocabulary. Successful students emerge able to speak at a basic level, and perhaps also to read a book, in the language. These skills are a nice beginning, but they are nowhere near sufficient for actual communication.

Americans face an additional obstacle to learning and retaining languages. English-learners in other countries have myriad opportunities outside the classroom to practice speaking with people who are proficient in English. But unless Americans grow up in a bilingual family, they are unlikely to get any reinforcement of their classroom learning. And so when the classes are over, most people quickly forget what they have learned. Yup, me too. After two years of college French, I retain just enough of it to read my mail (which for some inscrutable reason is occasionally in French) and to engage in halting chit chat with my neighbor Rodolphe. Admit it: Vous avez oublié votre français aussi, n’est-ce pas?

School language classes are ineffective in yet another way: They disincentivize making mistakes. But the only way to learn a language is to let go of self-consciousness and to get out there and speak as much as possible, mistakes and all. I have no talent for languages whatsoever; any success I have achieved is owing to my wonderful teachers, but also to my utter shamelessness—to my willingness to talk with anyone at any time, not caring one whit about looking foolish. In high school and college classes, by contrast, students are graded on their accuracy. Anxiety about grades can encourage students to be overly cautious. Worse, many students are afraid to mess up because they don’t want to look awkward in front of their crushes, buddies, or bullies.4 And so they don’t get the practice they need.

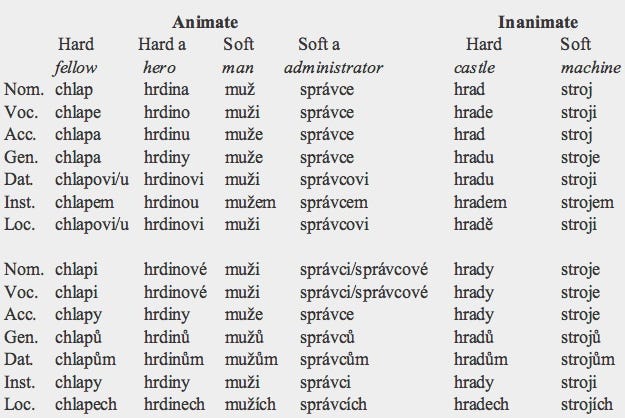

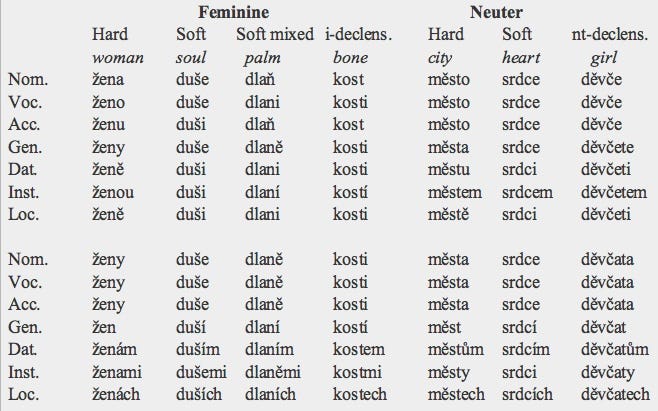

The sad truth is that unless we have an extraordinary aptitude for languages, we will not learn enough from classroom study alone to obtain much benefit. For me to learn enough Czech to become friends with Marta,5 it took 150 hours of private language lessons, followed by a weekly conversation group, plus hundreds of hours of homework, plus, obviously, living in a country where everyone speaks Czech. (To be fair, Czech is tough! It has four genders—not nearly as much fun as it sounds—and seven cases. Below are two typical declension charts; view them and tremble! And these charts don’t even include adjectives, which are declined in yet another way.)

Life Is Long

Language classes in school aren’t sufficient, and they aren’t necessary either. I think we sometimes get caught up in fears that if we don’t make children study a subject in school, they will lose their chance and never, ever learn it. This is a baseless fear, though. Americans learn languages as adults6 all the time, but they do so because they have a reason to (or more of a reason than “I need to pass this class in order to graduate”). They fall in love with someone from another country, or fall in love with the country itself, or move overseas for work (or, in my case, their husband takes a job in Prague and they come along for the ride). Or they join the US military or the diplomatic corps, both of which offer some of the finest language training in the world.

All is not lost. According to a 2023 survey, nearly a third of all Americans have tried apps like Duolingo, Rosetta Stone, or Babbel. Of course, these apps alone will never get anyone to fluency, and most people use them just for fun. But some users go on to further study, practice, and even mastery. Life is long! Pace the defeatism of the J. Alfred Prufrocks among us, “indeed there will be time.”

If I Had a Magic Wand

Alas, this humble essay is unlikely to prompt any actual change in the world. I am again whipping the Hellespont. But if I had a magic wand, I would wave it to improve foreign-language instruction so that it better accords with the way we learn and also honors our talents, in all their magnificent variety:

Beginning in pre-k and continuing through fifth grade, all US public school students would take Spanish for thirty to forty-five minutes per day. The sessions would be play-based, with no grading, tests, or homework. I can imagine kids playing board games or out on the playground, cooking a dish, singing songs, making art, or watching a children’s program, all in Spanish. In fifth grade, teachers would observe the students to find out which of them have an interest in and talent for languages, and they would strongly encourage those students to take elective language classes in middle school and high school. And no one else—neither in middle and high school, nor in college—would have to take a language class unless they wanted to. Instead, they could take electives in art, music, sports, or chess, or whatever suits their talents and inspires them to explore and grow.

How about you, readers? What do you think of these ideas? Have I persuaded you? Or not really? Do you speak another language? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Extreme polyglots have special talents the rest of us mere mortals can only dream of. Take Trevor Noah, who speaks eight languages, as well as—apparently based on the video below—some French and Spanish. One reason for his success at languages is his astonishing ear for accents. In this video, Noah’s impressions include Trump speaking Arabic and a French rapper stranded in Atlanta. Plus he shows off such accents as posh and middle-class English, white and black South African, Spanish, Haitian, Trinidadian, and American. Amazing!

I often have occasion to think of David Sedaris’s joke (I think it’s in Me Talk Pretty One Day) that Germans are always asking him to “please allow me to practice my flawless English with you.”

Throughout this essay I refer to Americans, but in fact all English-speaking countries have comparable rates of monolingualism to that of the US.

Seriously! They had, like, eight kinds! Why?!

It could always be worse, though. There exists a book—and I swear I am not making this up—called Learn German with Kafka in the Penal Colony. Um, no thanks.

Here are my eccentric levels of sub-fluency: At the lowest level, baristas at Starbucks don’t immediately switch to English the minute they hear you speak. At level two, native speakers praise your efforts fulsomely. At level three, native speakers correct your mistakes and encourage you to do better. At level four, you can have a long conversation with a patient friend.

No one would ever consider me fluent, but I did get to level four in both Czech and German.

I recommend Scott Alexander’s article “Critical Periods for Language: Much More Than You Wanted to Know.” Scott H. Young, whom Alexander quotes, has found that “‘given the same form of instruction/immersion, older learners tend to become proficient in a language more quickly than children do—adults simply plateau at a non-native level of ability, given continued practice.’”

In a separate article, Young debunks the concept of critical periods, noting that adults have some advantages over young children in learning languages, including not only motivation but also proficiency in one’s own language, which “gives you a reference point to learn from.”

Totally with you here on the point that the teaching/learning model in American high schools is not the way to learn. I teach at a university (in design, not languages), and students who had even years of Spanish or French in HS can't converse in their language of study.

For me personally, however, I am so grateful that I learned other languages: Latin in HS (Catholic), German in college (Georgia State University required a year of foreign language), and then self-taught Italian (because I teach in Rome sometimes). I am a huge logophile, so maybe this explains why this matters so much to me. I am fascinated by words and their etymologies to the point that sometimes I can be annoying, or at least people look at me funny.

There is another aspect of foreign languages that brings me great joy: out-loud pronunciation of words or names. One of my favorite things about learning German was speaking the language, with all those weird sounds that English doesn't have. Same with Italian. And I even get a kick out of learning proper pronunciation for words in languages that I don't speak, such as Mandarin Chinese. I am a name-reader at my university's commencements every semester, and one of my greatest joys is reading the student names into a microphone that makes my voice reverberate to the rafters of a coliseum filled with 20,000 happy people—knowing that I "nailed" it.

It's a great role for me, because I have both a voice and a face that is perfect for radio :·)

P.S. Matthew just seems so damn tortured. And what's with his hair? I'm sure that someone with a bazillion lbs a year owns an ivory comb? I'm Team Colin, but it's just because I think he's cuter.