I am a quitter. This isn’t me being self-deprecating or fishing for compliments. I am proud to be a quitter and believe that more people ought to quit—and more often.1 As the comedian Mike Birbiglia once said at the conclusion of a heartbreaking story about being bullied,

at the end of the year I came up with a different idea, which was to quit. And I ran this by all the adults in my life: my teachers, my parents, my guidance counselor. And what’s surprising is that no one tried to talk me out of it. They didn’t say those things that you hear in the after school specials. Like, hey, buddy, don’t give up. And stick it out champ. Or, don’t let them get the best of you, ace.

The best of me was off the table, and everyone knew it. Somehow I’d become the fall guy for the entire ninth grade class. I symbolized a certain kind of kid, the kind of kid who everyone hates. So I left. . . . And here’s the truth about life that they never tell you in those after school specials. Running away works.

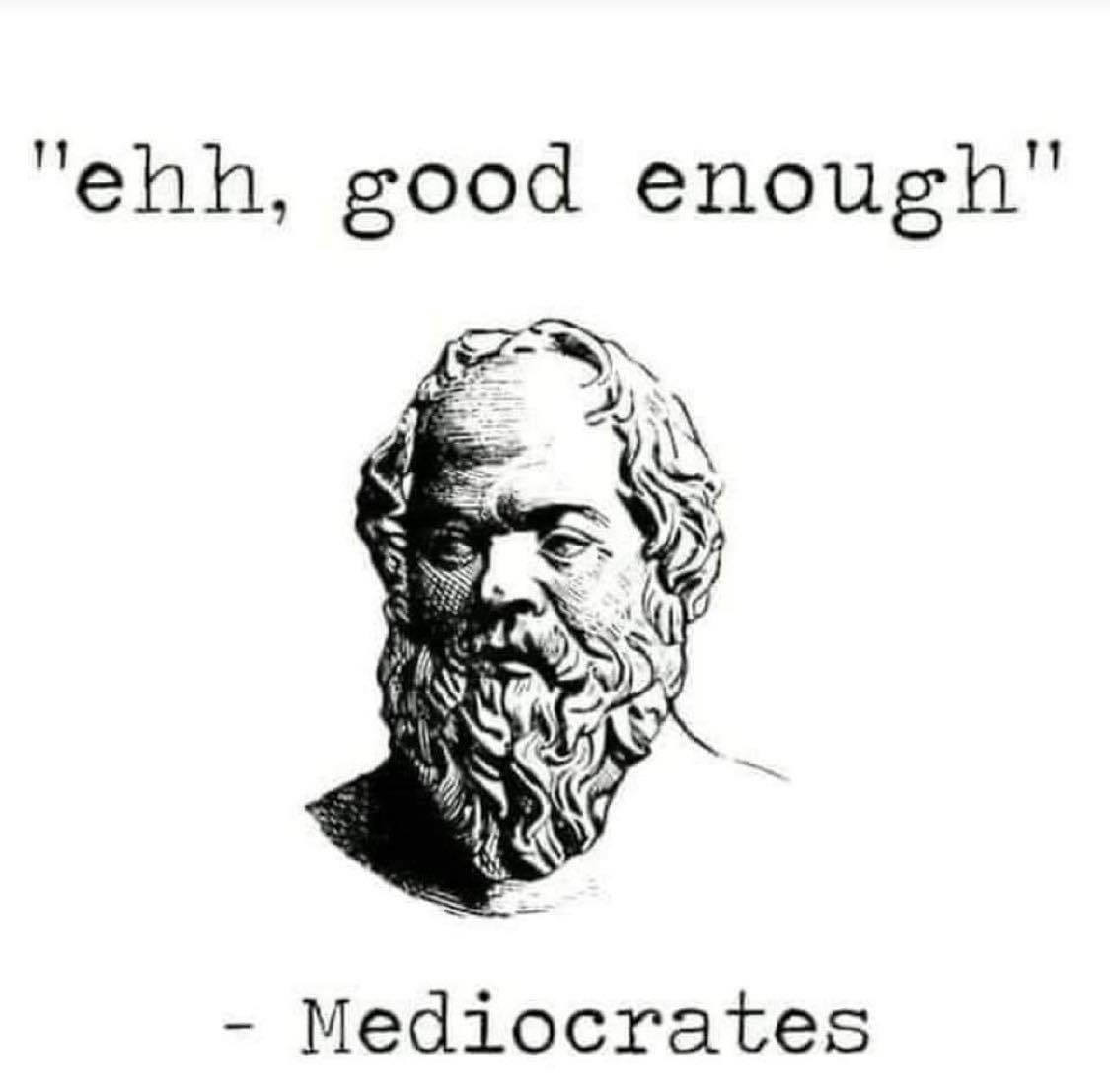

We could learn a lot from this portly, contented fellow:

The Curse of Rabbit Meadow

Quitting has been on my mind since last week, when I tried and failed for the second time to hike to the summit of Hasenmatt, a mountain in Canton Solothurn. I have written before about my hobby of hiking to the summits of mountains—twenty-eight times so far. So why have I been stymied twice by Hasenmatt, uniquely among all the mountains I have attempted? Hasenmatt stands a mere 1444m/4740ft, and hiking to the top requires no special equipment or technical knowledge. Humiliatingly, the name Hasenmatt means “rabbit meadow.” (Leave it to the Swiss to refer to a mountain as a meadow when hikers must ascend a vertical 824m/2703ft from the trailhead to the summit.)

The reason I quit? Snow and safety. Turns out that early spring is a poor time for a mountain hike. My first attempt two years ago, up the north side, had to be aborted short of the summit, when it became obvious that it would be impossible to continue to scale the steep, icy slope safely. Once I succumbed to the inevitable and turned back, I had to descend the worst part by lying flat on my back for maximum friction, braking with my poles and heels. This was not nearly as fun as it sounds,2 but at least the hairy bit was shorter than it would have been, had I bullheadedly persevered the whole way to the top.

Last week I quit even earlier, with a couple of kilometers and some two hundred vertical meters still to go. I had felt very clever about choosing the southern approach this time, figuring that the sun would have melted the snow—but forgetting that that would mean a trail covered in slush (also slippery, especially when scrambling over boulders). And then it started to sleet. “OK, Mother Nature, point taken,” I thought, and turned around, while my dog, apparently thinking, “Finally! What took you so long?” raced downhill ahead of me.

My dog was smarter than I was. Quitting is often more sensible than powering through, damn the torpedoes and full steam ahead. Our culture admires grit and perseverance, but really we ought to celebrate quitting too.

The Problem with Grit, Or, Why Pay Twice?

Readers are probably familiar with the concept of grit, as promulgated by Angela Duckworth and many other education experts. Duckworth defines grit as “passion and perseverance for long-term goals. . . . And grit is holding steadfast to that goal. Even when you fall down. Even when you screw up. Even when progress toward that goal is halting or slow.” Obviously grit is an excellent quality that we should be encouraging in ourselves and our kids, right? It is good to be able to persist and to refuse to give up when confronted with setbacks. Without grit we would still be hunkering down in caves, eating grubs, and dying of sepsis.

And yet grit as it is understood in our culture, especially in education, causes pointless suffering. Education reformers love to talk about inculcating grit in our kids so that they will work hard and stick with tasks. The reformers might be better off instead asking themselves why their ideas impose such developmentally inappropriate, irrelevant, and unpleasant tasks on kids—for example, why schools inflict seat time and worksheets on kindergartners; why almost half of US states require all high school students to take Algebra 2, which most of them will never use after graduation; why standardized testing consumes class time formerly devoted to PE, science, art, and music; and why elementary reading programs drain reading of all joy by focusing not on stories but on “passage analysis” of “informational texts.” No wonder kids lack grit when confronted with these Gradgrindian tasks.3

An emphasis on grit in these situations is victim-blaming. Students are struggling not because they (or their teachers) lack grit, but because education experts are asking them to take on challenges for which they have little interest, use, or talent. And in fact anyone who has observed children engrossed in a beloved activity—building with Lego, or immersed in a favorite book, or practicing soccer skills, or caring for a pet, or perfecting a cookie recipe, or memorizing facts about dinosaurs, or quietly observing nature at a park, or anything else they do for fun—knows that we all are capable of admirable grit when tackling a project or goal, so long as we choose the project or goal ourselves.

Not only in education, but in all areas of life, when we valorize grit we risk falling afoul of the sunk-cost fallacy—our tendency to persist in a futile endeavor simply because we have already invested time and effort in it. Our culture has a well-intentioned but false belief that we can do anything if we just set our minds to it and try really hard. But we’re better off putting our time and effort into endeavors that matter to us, goals we can achieve, and experiences we enjoy. My father-in-law had an amusing way of pointing out the folly of the sunk-cost fallacy: Sometimes, at a play or concert, he would feel bored or tired—or the show would be bad. Rather than sit through the whole thing to justify the cost of the tickets, he would leave at intermission, because, in his words, Why pay twice?

A Short List of Things I’ve Quit

In the hopes of inspiring readers to fess up to quitting, I’ve assembled a short list below, out of the many examples I could cite, of things I’ve quit. In each case, quitting something hopeless enabled me to try something new.

Piano, twice. When I was eight, I participated in an enormous number of activities (two choirs, the school play, Girl Scouts, piano lessons, and religious school), and my mom noticed that I was anxious and stressed. She told me that I could pick any two activities and quit them.4 So I quit piano but resumed lessons a few years later, with a better teacher. In high school I studied piano at the conservatory of the local university; practiced upwards of two hours a day; and had the opportunity to perform French suites by Bach, sonatas by Beethoven, études and nocturnes by Chopin, and many other great works. Sadly, at college it became clear that while I had been pretty good for a high school student, I was not in the same universe as people who were preparing to become professional musicians. Besides, I liked singing better than piano. So I quit piano and switched to voice.

My dissertation. After five years of grad school, I had finished my course work, passed my oral exams, and drafted half my dissertation. But I was miserable, and my fellowship, which had been covering tuition and paying me a stipend, was about to run out. In order to continue, I would have had to soldier on with student loans. No thanks. I have not regretted the decision to quit grad school for a single moment. I switched to teaching, which was much more rewarding, both spiritually and financially.

Several books every year. A librarian of my acquaintance taught me a useful rule: Take your age and subtract it from a hundred. If, when you’re reading a book, you haven’t gotten into it by the corresponding page, then you can give up on it with a clear conscience. We have limited time for reading, and if a book isn’t working for us, quitting it frees us up to switch to one we like better.

Running, also twice. In grad school I used to run twenty-five miles a week but was halted in my tracks (literally) by plantar fasciitis. So I switched to biking. I started running again when my kids were young and trained for and ran three half marathons but was forced by age and general creakiness to quit. So I switched to hiking.

Quitting As a Spiritual Practice

Most of us agree that it is good to quit dangerous situations and activities—running while injured, hiking an icy mountain trail, smoking, an abusive marriage, and the like. But we tend to look askance at people who quit for lesser reasons—just because it’s not fun anymore, just because it’s difficult, just because it takes too much money or time, or, heck, just because. We think, “Why didn’t they stick it out? How lazy and flaky of them! I would have tried harder!” But would we though? When a project is imploding, or a situation is unpleasant, or a goal seems pointless, don’t most of us eventually recognize that uncomfortable reality and try something else? In fact, we should think of quitting not as giving up, but as switching. After all, when we quit, most of us don’t simply sit on the sofa eating bonbons; we switch to something new to see if that works better.

Quitting is a spiritual practice because the decision to quit requires many virtues. In order to quit, we need the humility and grace to acknowledge our own human weaknesses. We need to notice and respect the tremendous talent and hard work that mastery of a skill, sport, art, or academic subject requires. We need the awareness that time is the one resource in life that is truly limited, and the determination to spend the little time we have been granted wisely. We need gratitude for our own unique interests and abilities, which we honor by pursuing activities that suit them. We need an openness to stopping now and maybe trying again later. We need the courage to refuse to follow our culture’s precept that everything ought to be optimized.

Many years ago I read The Alchemist, by Paolo Coelho, for a book club. It is an allegorical story of a young man who dreams of a great treasure and embarks on a journey to find it. He never gives up and sacrifices everything—home, family, and love—to attain it. At the end, he gets his treasure, which is meant to be a happy ending. Sigh. Everyone else in the group loved the book and found it inspirational, but to me the book’s message was pernicious, because the treasure was not worth the cost of getting it.5 The young man in The Alchemist, blundering on, spending precious time and forsaking relationships in the singleminded pursuit of his goal, was not a role model. A better role model is Mike Birbiglia, and all the quitters like him, who show us that it takes guts to quit, to say that we gave it a try, to accept that we didn’t reach the summit of achievement, and to insist that that is ok. When we quit, we testify to the truth that “good enough” is pretty terrific.

How about you, readers? What is something you’ve quit? Do you regret it, or was it a wise decision? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

This was one of my favorite pieces to play when I was in high school. It is joyous and playful and also has the advantage of sounding impressive while actually being quite easy. Follow along in the music as you listen to Daniel Barenboim’s outstanding performance, and you’ll see what I mean.

Readers, I wanted to Rickroll you—my plan was to make the above video link not to a Schubert Impromptu but to “Never Gonna Give You Up.” But alas I lack the technical chops for such a feat, so I quit trying. Please just pretend that I tricked you. Thanks. Anyway, the one thing we shouldn’t quit is love. Or at least Rick Astley thinks so!

Readers might be interested in Quit: The Power of Knowing When to Walk Away, by Annie Duke, a psychologist and professional poker player. I haven’t read the book, but I recommend this informative podcast about her ideas.

My American Eagle jeans held up remarkably well to this abuse, though. I am available for endorsements if anyone is interested.

In my darker moments I picture Angela Duckworth’s personal trainer ordering her to do a hundred pushups and, when she stops, exhausted, on pushup number thirty (or whatever), tsk-tsking and shaking his head sorrowfully over her lack of grit.

Readers, that is some good parenting right there. Thanks, mom! (And, for the record, Girl Scouts was the other activity I quit.)

The treasure was just money! If money was so important to him, couldn’t he have become a finance bro or crypto grifter like everybody else? No need to abandon his family and the woman who loved him!

I love the 100-age pages rule -- I'm making a note. My stepmother said something to me years ago that I didn't appreciate until much later (mostly because I thought it was backhanded); she complimented me on being able to quit. This was back when I was in my 20s and never lasting more than a year at any job because I'd always wind up bored out of my mind. But when I finally mustered the courage to walk away from my first marriage, she reiterated the sentiment, and I realized that she'd been sincere. Walking away was the hardest thing I had ever done up to that point, and I should have done it sooner, but I'm still grateful every single day that I managed to do it at all. Like your mom knew -- you have to make space in your life for the actual good stuff. If you're spending too much energy on pursuits or relationships that wear you down, it's impossible to find time for those that delight you. Why pay twice indeed!

I like that you linked to the poker player because I had Kenny Rogers' "The Gambler" running through my head as I read this. "You gotta know when to hold 'em. Know when to fold 'em. Know when to walk away. Know when to run."

Myself, I quit professions. Teaching English, accounting, and the law. Each time right when things were going well, when I was on "top of my game". It often doesn't look good in others' eyes. People assume something must have gone wrong. "Why would you walk (run?) away from a good thing?" For me it's always felt natural. Quitting from boredom I guess?