Many years ago, I came up with a great idea for a business: Rent a Yenta. I imagined my clients consulting me to get the scoop on a possible girlfriend, boyfriend, roommate, or business partner. The inspiration for this idea arose when a friend told me he had just rented out a room in his apartment to a guy I’ll call Jack. I knew from bitter experience that Jack always ducked out of our local hangout the moment the bill came. Worse, Jack was notorious for cadging money from people and not paying them back. “Why didn’t you tell me you were planning to rent him a room?” I asked. “I could have warned you!”1

But say I had known in advance that my friend wanted to rent Jack his room. What would be the right thing to do then? Warn my friend, or give Jack a chance? What do you think?

Another time I was a yenta for a friend. Straight single men were thin on the ground in our department, and one of them, whom I’ll call Steve, had seized the opportunity to cut quite a swath through the women. I knew from friends that Steve was a player rather than a relationship guy. He asked my friend out, and she asked me about him. She wasn’t looking for a one-night stand, so I told her what I knew. Should I have? Again, what would you do?

Gossip has been on my mind because of a recent New York Times article by Michal Leibowitz, about people who refuse to gossip. After reading the article, I was torn. On the one hand, I am on the record as making the case for busybodies, because they enforce social norms and pass along information that will protect the community from malefactors. But on the other hand, as everyone who has been the target of gossip knows (i.e. every person ever), gossip is just horrible.

Gossip damages not only its targets but also the gossips themselves; it wastes our time, destroys our relationships, and keeps us mired in negativity. Leibowitz lists several advantages of abstaining from gossip:

I was intrigued by [the abstainers’] optimism, by their grace, by their commitment to judging others by their best features. Which is not to say I’ve sworn off gossip entirely. But I’ve definitely cut back.

And what do you know? The less I judge people, the less I want to judge people. The less I complain, the less I want to complain. The less, maybe, that I even see things to complain about.

The Evil Tongue

Loathe as we may be to admit it, religious law and secular ethics alike are unambiguous in their condemnation of gossip. Jewish law takes this principle one step further; its prohibition of lashon hara (“the evil tongue”) refers not to spreading lies (that particular rule is one of the Ten Commandments), but rather to sharing even true information about someone if that information would be in any way damaging to them. Which makes sense: Unless we’re protecting another person from imminent harm, we ought to keep people’s secrets to ourselves, if for no other reason than that there are more interesting topics than other people’s failings.

Besides, if we are honest with ourselves, don’t we sometimes share others’ private information for a dishonorable reason—to demonstrate our social power and to enhance our status? Gossip is a popularity cheat code. Being privy to lots of secrets makes us look trusted, cool, and (literally) in the know. I’m not pointing fingers here; I have used gossip for self-aggrandizement too, and I’m not proud of it. Before repeating someone else’s secret, even when it’s true, and even if it’s something positive, we can ask ourselves, “Am I sharing this to help other people, or myself?” and act accordingly.

We Want a Loophole!

Gossip is only human, and so whenever gossip is criticized, we will look for loopholes to justify our inclination to rumor-monger. The Times article is no exception. Several of the top-rated comments defend “venting” to friends, arguing that it’s ok to complain about how other people treat us. True, griping about our foes feels good in the moment—we all love it when someone pities us, takes our side, and inveighs against those who have allegedly injured us—but excessive venting is bad for our mental health and our relationships alike. Venting is actually a poor metaphor for our psyches, because it’s inaccurate. We aren’t steam engines that require a pressure valve to function properly. When we vent, more often than not we build up, rather than releasing, pressure; stewing over problems almost always makes us feel worse. Plus, when we use our friends as misery dumps, they may start avoiding us. Venting gets tedious!

But the main problem with venting is that if we vent to someone else, rather than speaking with the person who offended us, we will never resolve the conflict. Granted, speaking directly with the person we’re upset with is difficult, but it does enable us to actually fix or at least improve the situation. We may even discover that we weren’t completely in the right, and they weren’t completely in the wrong. It has been known to happen.

There’s also the justification that we’re sharing information to protect others. The following parable2 is convincing:

There was once a king who had a loyal wife and a beautiful daughter. The daughter fell in love with a commoner, and the king didn’t approve, so the king falsely accused the man of theft and sentenced him to be executed. The king bragged to the man that nobody knew the accusation was false, so no one would save him. But the man said, “You have the most trustworthy wife in all the land. Surely you can tell her.”

So the king did. And because his wife was so trustworthy, she told only one person, her loyal maid. And because the maid was so loyal, she told only one person. And so it went, until the sun rose.

That morning, the king took the man out to be executed. But every person in the kingdom had heard from a very loyal friend that the man was innocent. They raised a great fuss, and so the king was forced to set the man free—all thanks to gossip.

Well, ok, yes, OBVIOUSLY if you’re privy to information that will save someone’s life or keep them out of danger, go ahead and tell. Reporting a potential crime isn’t really gossip anyway. I think this parable is the exception that proves the rule.3 Most of the time our information isn’t life-or-death, much of the time we have incomplete or incorrect facts, and some of the time the damage our gossip will cause outweighs the benefits. If we’re planning to gossip in order to protect people, it’s wise to tread carefully. We can all think of cases where cultural warriors combed self-righteously through their enemies’ online histories or outed them for some misbehavior or other in order to expose them as villains. Most of these cases (ahem: Al Franken) didn’t age well.

Socrates’ Razor

Socrates is reported to have said that before we repeat a story about someone, we should first ask ourselves whether the story is true, necessary, and kind. Now, I am too lazy to wade through all 1800 pages of my college edition of Plato to find out whether Socrates actually said this, or whether it is an internet legend.

But regardless of its origin, this idea, which I’ve dubbed Socrates’ Razor, is useful for us when we’re thinking about whether to share something we’ve heard. Even two out of three—chitchat that is true and necessary, true and kind, or necessary and kind—is progress.

The Irish Exit and Other Strategies

By now you have likely guessed that while I occasionally backslide, I dislike gossip and try not to indulge in it. We can all strive to follow Socrates’ Razor before we speak. But what about when other people are gossiping in our presence? When I’m in a group and the talk starts to veer into trashing and tittle-tattle, a couple of strategies can turn the talk in a more positive direction. Often I just change the subject by asking a question about some factual matter—“Hey, does anybody know what time the bake sale starts?” This usually derails the conversation. Other times I’ll just interject “Oh, I really like her!” or say something positive about the person—“Did anyone try her fantastic brownies at the last bake sale? I want her recipe!” This usually gets the message across.

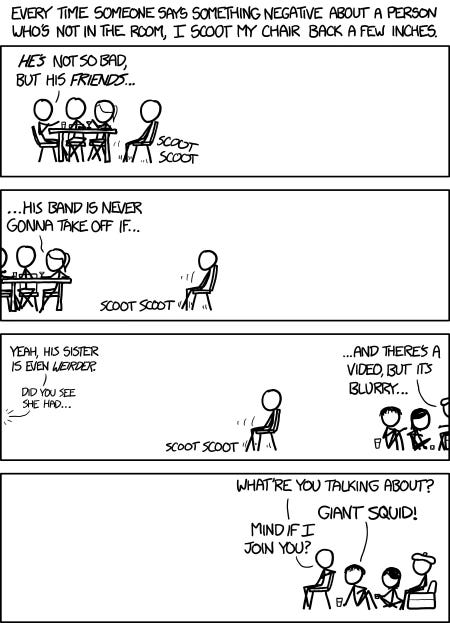

Other times more radical measures are called for. For example, at school pickup one day, an acquaintance rushed over to tell me that another mom had gotten a tummy-tuck. “Huh. How do you know that?” I asked, and added that the woman in question was a personal trainer, so there might be another explanation for her svelte figure. “How do you know that?” or “Why do you care?”are valid rejoinders to snippy remarks, in my opinion. In worst cases, I resort to the Irish exit and just drift away. I was gratified to discover that I’m in good company, and that the cartoonist Randall Munroe of xkcd uses this strategy too:

To return to the two dilemmas I posed at the beginning, I think the Jack case passes Socrates’ Razor. It was true that Jack tended to stiff people, it would have been necessary to tell my friend this in order to save him financial trouble, and it would even have been kind to Jack to forestall his taking on more expenses than he could handle. However, I remain torn about whether I was right to tell my friend about Steve. As far as I knew, Steve wasn’t violent or dangerous; he was just a cad. I had no reason to assume that Steve’s past behavior would continue into the future. My friend was pretty terrific. Who knows? She might have converted Steve from his tomcatting ways, had I not meddled.

How about you, readers? Do you gossip? If so, do you feel guilty about it, or do you think gossip has value? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

The following video (h/t my friend Claudia) has nothing whatsoever to do with today’s topic, but it is quirky, goofy, and delightful—I promise you will get a kick out of it. The bass player cracks me up, and the maraca lady is pretty cute too. If only we all could conduct ourselves with such un-self-consciousness and verve!

And in fact Jack soon fell behind on the rent. My friend ultimately had to call Jack’s mother to get the money he was owed.

Thanks to my daughter for the parable, which she read somewhere online. We couldn’t find the source, unfortunately.

I am aware that “proves” in this expression actually means “tests,” but colloquial English spoken here.

The true, necessary and kind thing has also been attributed to the Buddha: https://fakebuddhaquotes.com/if-you-propose-to-speak-always-ask-yourself-is-it-true-is-it-necessary-is-it-kind/ but turns out to be from the Victorians, who were also thinking about when to gossip!

There's a more extreme version of some of your examples where the gossip network is the only way to get the message out that so-and-so is a known rapist, which is definitely ok with me under the "protecting life" heading.

Even in the Steve case, I think there's a strong argument, if your friend asked "What's Steve like?", to tell the truth just in case she's asking some form of "Is he a predator?" If the answer is "bit of a cad, but nothing worse than that" that's still useful information to have.