In what is becoming an annual tradition, it is again time to talk about The Bear for Labor Day. (Here is last year’s post—with bonus Tom Cruise!) For readers who are unfamiliar with the show, The Bear, whose third season came out at the end of June,1 tells the story of Carmy, a famous chef who inherits his brother’s greasy-spoon, Chicago Beef, after his brother dies by suicide. Seasons one and two introduce us to a motley crew of workers, and to Carmy’s horrifyingly dysfunctional alcoholic family. Against all odds, Carmy, his sous chef, Sydney, and the team convert part of Chicago Beef into a high-end restaurant. In the process, the characters achieve meaning in their lives through the dignity of work.

Fans of the show may disagree, but I found season three a bit disappointing. For one thing, it has its ponderous moments. What is up with all the extremely tight close-ups and extended, meaningful pauses? And the lugubrious Trent Reznor score doesn’t help either. I kind of miss all the yelling.

The Bear Is a Metaphor

But a more important issue is that season three suffers from a thematic tension, a tension that our country is also grappling with right now. Do we celebrate ordinary workers and the power of people working together, or do we worship elite geniuses and charismatic leaders?

By far my favorite aspect of The Bear is how, throughout its three seasons, it has honored all kinds of work—of doing our best, even if the task is just polishing spoons. We see more hard physical labor in The Bear than in any other show, ever. More plaster dust, more sweat, more scrubbing, more hoisting heavy pots, more hauling furniture around, more breaking down boxes in the dumpster. To me the most beautiful moment in season three is the opening of episode two, which shows regular Chicagoans doing their ordinary jobs with professionalism and good cheer. We see line cooks, forklift and Zamboni drivers, bakers, servers, cleaners, meat processors, and firefighters, among others. I am a great big softie, so your mileage may vary, but this sequence brings tears to my eyes.

My favorite episode is “Napkins,” which tells the backstory of Tina, one of the restaurant’s workers. At the start of season one, Tina had been the most intransigent and hostile worker at Chicago Beef. She resisted all Sydney’s suggestions and sabotaged her. Sydney and Tina gradually iron out their differences, Tina becomes a dedicated and capable worker, and Sydney rewards Tina with a promotion.

“Napkins” shows us why Tina had been so resistant to Sydney. Before Tina came to Chicago Beef, she had a well-paying office job. Tina’s company lays her off, and she is unable to find a new job, in spite of applying at dozens of places. We see how she is constantly disrespected because she “only” has decades of experience, but no expensive academic degree. We see her constant, grinding worry about money. We see how the stress damages her relationship with her son: Their only interactions in this episode are when Tina yells at him from another room. No wonder she was so suspicious of the young, college-educated whippersnapper Sydney at first. “Napkins” shows how important and unusual Sydney’s support of Tina’s career is; Sydney sees beyond Tina’s lack of a college degree and honors her hard work and achievement.

But along with these stories about the struggles and pride of ordinary workers is the show’s other aim, to celebrate a tortured, perfectionistic, high-status genius. We’re supposed to sympathize and care deeply about Carmy, and in the first two seasons we did. But in season three, Carmy’s pursuit of greatness causes problems for his workers. Every day he changes the menu at the last minute, which creates more work and stress for everyone. Carmy is in danger of perpetuating the cycle of abuse and of becoming the kind of tyrannical top chef who had been so cruel to him in the past. (And, to be fair, the show intends us to see this as a problem.2)

In addition, both Carmy and the show treat Carmy’s erstwhile girlfriend, Claire, who is a pediatrician, as a mere convenience. With one exception,3 Claire exists to listen to, admire, and be patient with Carmy, rather than being a person who might have her own challenges and anxieties. At one point Carmy’s friends, the Fak brothers,4 interrupt Claire at the hospital to beg her to forgive Carmy for unceremoniously dumping her at the end of season two. But Claire has a more important job than resolving Carmy’s unresolved trauma. Let the woman get back to healing sick kids!

The Bear is a metaphor because the showrunners, and all of us, need to figure out what we most care about, and where we will put our energies and resources—the achievements and status of a talented elite, or the hard work and progress of regular people?

Perfect Days and the Parable of Heaven and Hell

A complement to The Bear is Wim Wenders’s beautiful film Perfect Days (2023).5 The film follows a middle-aged man, Hirayama, through his daily life. Hirayama lives in a tiny one-room apartment. Every morning, he suits up and drives his beat-up van to several public toilets, which he cleans and maintains. While most of us would never choose Hirayama’s life, he always wears a beatific and infectious smile.

Perfect Days’s attention to a humble janitor contrasts with season three of The Bear, whose focus keeps drifting from the team of workers to the glamorous main character. Leaders in Japan originally pitched the film to top directors because they wanted to promote nine architecturally significant public toilets, designed by star architect Sou Fujimoto. The toilets had been built for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, but because of Covid, they hadn’t gotten the audience they deserved. (And the toilets are extremely cool, no question; you can see a few examples in the video.) Wenders took on the project, but he chose to celebrate not a great artistic genius, but instead an ordinary worker who performs a job we would normally consider the lowest of the low.

And yet when we think about it, there are few workers who are more important to our daily lives and the economy than people who clean and maintain public toilets. Clean and safe public toilets are necessary to our ability to work and shop in comfort, and they are especially important for women. Until a few generations ago, women were tethered to the home by the urinary leash, and even now the lack of safe public toilets in developing countries is literally life-threatening for women. Readers, the next time you are in a public bathroom where a cleaner is working, take a moment to thank him or her. I always do.

Hirayama’s contentment stems not only from the importance of his job, but also from his inborn capacity for joy, which the film depicts through the pattern of light through tree branches. In an interview, Wenders explains the meaning of this motif: Hirayama had been a rich and powerful businessman, but his life had no meaning. One day, he wakes up, hungover and alone in a sleazy hotel, with no memory of the night before. And then,

miraculously, early in the morning, there’s this ray of sunlight appearing on this wall in front of him. And it falls through the little tree in front of the window. There is this play of leaves and sunlight and shadows moving, and he looks at it and stares at it and he starts crying, because he’s never seen anything so beautiful. He probably has seen it, but he hasn’t noticed. Then he realizes that’s the answer to his existential crisis, to become somebody who notices that. He gives up his expensive car, his business job and becomes a gardener and eventually, the guardian of these toilets, because they’re all in little parks.

Hirayama’s gratitude and joy remind me of the parable of heaven and hell. In hell, everyone is starving even though they are surrounded by bowls of soup. The problem is that the spoons are so long and unwieldy that people can’t feed themselves, and everyone is frustrated and furious. In heaven, it’s the exact same setup; the only difference is that in heaven everyone is happy, because people are feeding each other.6

Hirayama, too, is happy because people are feeding each other: Japanese society is set up to make life easier and more pleasant for ordinary workers. Japan is a high-trust society, in which everyone takes responsibility for maintaining public spaces (famously, Japanese schoolchildren clean their own classrooms, for example). So Hirayama’s job is easier than it would be in countries where people are more careless. And indeed, the bathrooms in the film are pristine even before Hirayama gets to work.

But there are also systemic reasons for Hirayama’s happiness. Japan is more equal than the US; its Gini index is .33, compared with .45 in the US. Japan also has universal healthcare and a social safety net. So low-income people in Japan don’t experience the miseries of extreme poverty. And in contrast to low-wage workers in the US, Hirayama doesn’t need to cobble together multiple part-time jobs in order to scrape by. His reasonable hours at his single job leave him plenty of leisure time to listen to music, read books, and hang out with friends at the local bar. His employer has no expectation that he be available around the clock, and Hirayama does not suffer from the stress, disruptions, and sleep deprivation caused by just-in-time scheduling, which is still common in the US.

Our country is currently engaged in a debate over whether societal problems should be solved through systemic change or through individual action. But why can’t it be both? We can strive to control our emotional response to our circumstances. We can focus on gratitude instead of grievance. We can make sure to appreciate ordinary workers and do what we can to make their jobs easier. But we regular people also need laws that protect us from injury at work, that give us a predicable and manageable workday, and that pay us a living wage, so that we, too, can enjoy perfect days.

How about you, readers? Are you a fan of The Bear and/or Perfect Days? What are your favorite shows or films about ordinary workers? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

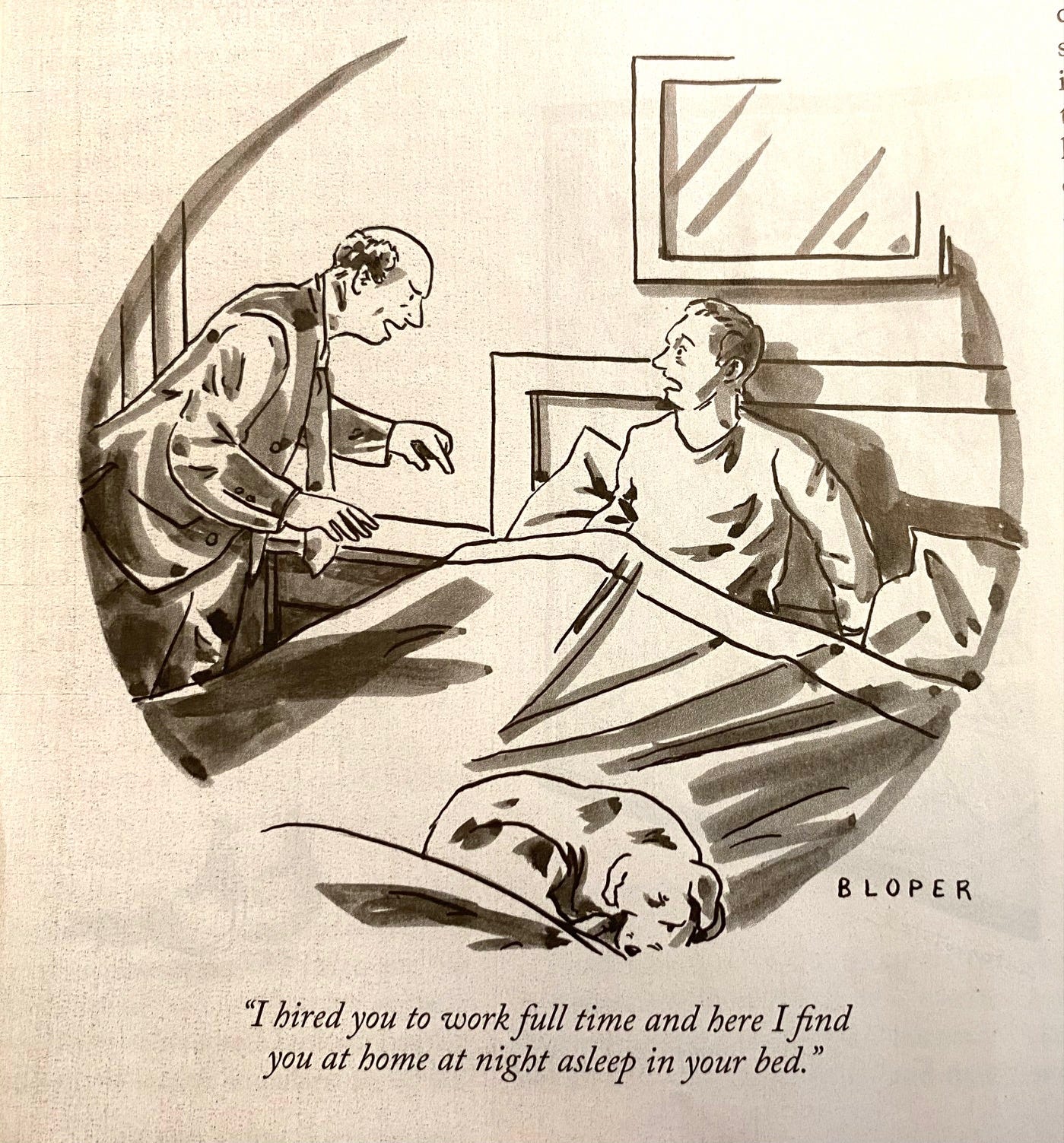

The other day, the Substacker Cole Haddon shared this meme on Notes:

I think this is an idea that can unite us all! What say you, readers? Are you in?

My guess is that fans of The Bear, like me, binged season three the moment it was released, but if you haven’t seen the show, be warned that this post has spoilers.

My son, a staunch defender of season three, has a theory that we will discover at the start of season four that the final shot of season three is making a point about cycles of abuse. We see Carmy reading the much-anticipated review that will either make or break the restaurant. We don’t see what the review says, but we see Carmy’s upset reaction, and we’re meant to think that it is a bad review. But my son thinks instead that the review is comparing Carmy with the top chef who had been so cruel to Carmy, and so Carmy is devastated to discover that people see him as the kind of abusive boss he had vowed never to be.

For a couple of minutes in one episode, Claire talks about feeling terrible that she didn’t read a patient’s chart carefully and gave her penicillin, causing a near-fatal allergic reaction. Carmy listens sympathetically . . . and then goes back to talking about his own issues.

That’s the other problem with season three: Way too much Fak brothers.

The source for the facts about the film and the quotation from Wenders is IMDb’s trivia page on Perfect Days, here.

When my daughter was younger, I took her out for ice cream. Her sundae came with an extra-long spoon, so she could scoop out the very bottom of her glass. When she saw the spoon, she cried out excitedly, “Look mom! Long spoons! Just like they have in hell!”

I agree that there's too much Fak brothers but I'll also stand up for being Team Carmy. Tortured genius is the way to go.

I have two more episodes of season 3 to watch and am finding it very heavy going. Watching Carmy implode through perfectionism is depressing. The show has stripped him of his humanity and vulnerability, which to me makes him unlikable. I'll watch to the end, but I'm not enjoying the season. There needs to be some joy and camaraderie to balance out the dysfunction and I'm not finding that. Fingers crossed I like how the season ends.