Many years ago in our New Jersey town, four families on our corner were best friends. The kids had weekend playdates, the moms went out for lunches and dinners, and the dads hung out and watched sports together. The families even shared a snowblower and traded off clearing each other’s driveways. One year, the wives all decided to go away for a ladies’ weekend, leaving the men in charge of the kids. One of the husbands said, with a sly grin, “No women! You know what that means, right guys?”

. . .

Get your minds out of the gutter, readers! This is a wholesome story! He continued, “Because the women aren’t around, we don’t have to cook anything. We can just order pizza!” And there was much rejoicing!

Potlatch and the Hostessing Arms Race

A potlatch was originally a gift-giving feast practiced by Indigenous people in the Pacific Northwest. Hosts of a potlatch would publicly destroy valuable items to demonstrate their wealth and status, to apportion resources, and to bind the community together. Nowadays, waggish types will sometimes refer to elaborate and expensive weddings, bar mitzvahs, and similar events as potlatch.

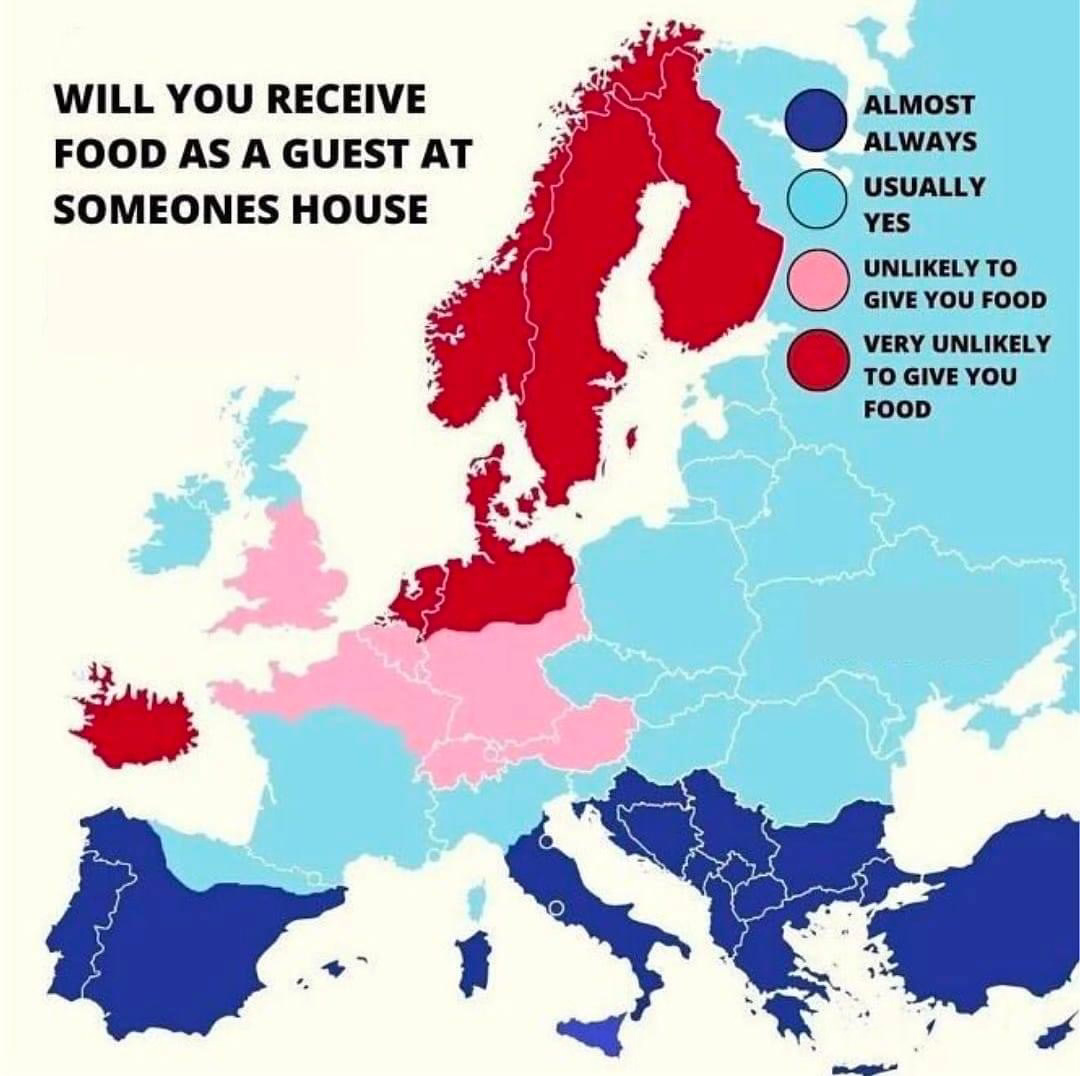

I believe that too often these days, casual social events can seem like potlatch too. I’ll admit my bias. I was raised among the descendants of immigrants from Scandinavia, a culture that, as the map below informs us, is very unlikely to give food to guests.

When I was a child, it was normal for us to run in and out of our friends’ houses to grab a drink of water, but no one expected the moms to serve us snacks, let alone the kind of curated buffet that is typically offered on playdates these days. It was the same for the grownups. Because my mom loves to bake, she used to prepare a special treat (Dream Bars! so yummy!) when she hosted her bridge club. This was the norm for hostesses back then—to offer guests one treat plus coffee.

By contrast, hostesses these days seem duty-bound to provide lavish spreads for guests,1 even when the get-togethers happen outside of mealtime. For example, I recently joined a Sunday-afternoon book club, and at the first meeting I attended, the hostess served coffee, tea, a variety of fruit juices and seltzers, and Prosecco in crystal glasses; toasts with caviar, mini-quiches with smoked salmon, and bowls of mixed nuts; and homemade cake and fancy pastries. And as though that weren’t enough, one guest brought a cake, and another brought cookies! All this hoopla was for only six guests, and because our meeting occurred between lunch and dinner, no one was particularly hungry. Hardly any of the hostess’s wonderful food was eaten.

Gourmet spreads like this are increasingly common in my experience. Over the years I have been to numerous nighttime book clubs, mid-morning PTC meetings, and mid-afternoon get-togethers, and they, too, have usually featured multiple drink options, one or two platters of cut-up fruit, at least two desserts, and several snacks, most of which sit there untouched on the table.

And these unreasonable expectations have only been exacerbated by social media, which makes us feel as though it’s no longer sufficient to provide tasty food—we also ought to create artistic displays worthy of Instagram (or TikTok or Pinterest) too. I mean, I yield to no one in my love of butter,2 but aren’t butter boards, pretty as they are, kind of a waste of time, and also, when you think about it, icky? Who wants to scrape up butter that has been smeared on a communal wood plank? And how do you clean the greasy board afterwards? But I digress.

Anyway, I suspect I am not alone in regretting this trend. We seem caught up in a hostessing arms race, with ever-higher expectations for the effort and expense required in order to have people over. And can we please dispense with the idea that the house has to be spotless before friends visit? (“Company is coming! Get rid of the couches! We can’t let people know we SIT!”):

These unreasonable expectations are a disincentive to inviting our friends—who has the time?—and they can even make us hesitant to accept invitations, because we don’t want to be obligated in the future. Potlatch culture stands in the way of the lovely, casual social encounters that make life so enjoyable.

A Happy Moment Called Company

I’ll let the comedian Sebastian Maniscalco introduce a better way:

This sweet comedy routine is usually invoked as a sign of how far our culture has fallen and how isolated and unfriendly we have become. And I agree that spontaneous visits with friends have become sadly rare. In my view, though, this change has come about not because our generation is uniquely selfish, but rather because we are responding rationally to much higher hostessing standards than were common in the past. Notice what Sebastian’s mom has bought for guests: “A little Entenmanns, some Sara Lee cake, just in case company came over. She made an announcement when she bought it, she’s like, ‘Listen, nobody touch this cake. This cake is for company only’”—plus “some Sanka.” It’s easy to be welcoming when all that’s expected from the hostess is inexpensive store-bought cake and instant coffee.

I would love to see our culture return to Sebastian’s mom’s way of hostessing—less focus on fancy food and drink and more focus on friendly conversation, and less time toiling alone in the kitchen and more time sitting together in the living room. Here are a few ideas to get us started:

Get takeout. If the hassle of planning and preparing elaborate dishes is preventing us from inviting guests, then what we should be giving up is the hassle, not the guests. As I mentioned a few weeks ago, my parents and several of their friends have enjoyed their gourmet club for more than fifty years. They are all in their eighties (except my dad, who is 91), and cooking is getting difficult for some of the folks in their circle. So the club still meets as often as ever, but now they choose whether they will cook or have takeout. Takeout, like love, is a doggone good thing.

Go outside. You know how most meetings could have been an email? Well, they could also be an excursion outdoors, on a walk or at a picnic table in the park, rather than in someone’s home. Walking out in the fresh air is healthier than sitting around anyway, and the outdoor location provides the perfect excuse to dispense with unnecessary food and drinks.

Go out. I used to lead an afternoon book club, and during the pandemic I seized the opportunity to shift our meetings from people’s homes to a local pub that had outdoor tables. People could order what they wanted (a beer for me, lunch for a couple of us, and nothing—it being the middle of the afternoon—for everyone else), and no one had to worry about being stuck with onerous hostessing duties.

Don’t go all out. If we are having guests outside of mealtime, we can limit our offerings to coffee or tea and at most one item of food—for example cookies or cake, either homemade or store-bought; or chips and dip; or chocolates. And if guests are coming for dinner, we don’t have to invent and execute new and complicated menus every time; we can perfect a signature dish and just serve that. Our guests know to expect my chili, and no one ever gripes or sneers. They don’t mutter darkly about my laziness or lack of creativity. No. They say, “Oh good! I love your chili!” It will be the same for you too, I promise.

The Sanka Pact

I don’t actually mean for us to start serving Sanka, which is an unpalatable brand of instant coffee that has fallen into well-deserved oblivion. “Sanka” is shorthand for a way of entertaining we ought to return to: Less fuss, more family, friends, and fun. (I even couched the pact in catchy iambic tetrameter so it’s easier to remember.) How do we bring this pact about? I have suggestions!

First, we have to be the ones to start, perhaps by trying the ideas above. When we step back from the hostessing arms race and toward relaxed authenticity, we are showing our friends that we care about them for themselves, and not as an audience for the impressive amount of money and effort we have put into entertaining them.3

Second, when we’re guests and are served only one dish—or nothing at all—we can forestall others’ uncharitable remarks and defend the hostess with some reframing: Hostesses who choose not to lay out lavish spreads or assemble photogenic food boards, be they butter, charcuterie, or what have you, are not being cheapskates; they are facilitating friendship by putting the emphasis where it belongs, on being together.

And finally, when we are guests and a hostess does provide a lavish spread, we can reframe that too: Her largesse is a sign of her special interest in and talent for entertaining, which she is generously sharing with us. But her generosity carries no culinary obligation for us. We can show our gratitude and reciprocate by sharing our own special interests and talents with her next time.

How about you, readers? Do you view hosting as potlatch or a pleasure? Will you join the pact? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

All of this is not to say that we should never bake for each other. Quite the contrary! Some of us are talented bakers who are happiest when sharing delectable treats with lucky friends. For example, my dear friend Anastasia. I am not normally a sweets person, but I make an exception for Anastasia’s pavlova, green-tea sponge-cake roll, and—especially—her lemon tart. Anastasia has kindly allowed me to share her lemon tart recipe with you all. This tart is quick, easy, not too sweet, and wonderfully creamy. It’s absolutely fantastic on its own, or covered with fresh berries, or with a cup of coffee adorned with a swoosh of steamed milk in the shape of a whale:

Anastasia’s Lemon Tart

Ingredients

For the crust:

1-1/2c (180g) flour

1 stick (100g) cold unsalted butter, cut into little cubes

2T sugar

Pinch of salt

1 large egg

Some cold water if necessary

For the filling:

Juice and zest of 3 lemons

3 large eggs

1c (140g) sugar

1/3c (25g) flour

2T cornstarch

1/2c (120ml) heavy cream

Method

In a food processor, pulse the flour, sugar, salt, and butter until crumbs are formed. Add the egg and process until the dough comes together. If necessary, add a few drops of cold water to help the dough along. Press the dough into a disk, wrap it in plastic, and refrigerate for 30 minutes.

Preheat the oven to 375F/190C.

Place the dough on a floured surface and roll into a 10–11” (24–26cm) circle. Transfer the dough to a lightly-buttered pie pan and poke a few holes in it here and there with a fork.

Line the dough with a piece of parchment paper and fill with dry beans or rice. You can also weigh the crust down with pie weights or—as I do—with three Pyrex ramekins.

Bake crust for 10–15 minutes and remove from oven. Remove the parchment paper and beans or rice or the pie weights. Reduce the oven temperature to 350F/175C.

Make the filling: Beat together the eggs, sugar, flour, and cornstarch. Add in the lemon zest and juice and mix until combined. Add the heavy cream and mix again.

Pour the filling into the crust and bake for 20–30 minutes, until filling is set.

Cool to room temperature and serve to grateful friends.

A couple of disclaimers: First, if cooking elaborate meals and/or baking fancy desserts is fun for you, please feel free to ignore this post and bake away! Far be it from me to yuck anyone’s yum!

Second, throughout this essay I refer to hostesses instead of hosts. This is on purpose, because I suspect that we women are imposing these expectations on ourselves and each other. If most men had their druthers, they’d serve guests chips and beer and be done with it. We women could learn something from them.

Except my mom. My mom’s love of butter, like Bottom’s Dream, hath no bottom. Take the sight below, which greeted me when I opened my parents’ fridge on a visit a while back (to be fair, my mom was planning to do some baking, but still). I come by my love of butter honestly!

Here’s an example of how to deescalate the hostessing arms race graciously: About once a month my husband and I and another couple alternate hosting dinners. Swiss etiquette mandates that guests bring a gift—usually chocolate, wine, or flowers. After several enjoyable dinners with our friends, one night they showed up for dinner at our place empty-handed. They had decided that we were such good friends that we no longer needed to observe the formal gift-giving ritual, but they knew that if they asked us to stop bringing gifts, we would ignore them and bring something anyway. They figured they had to be the ones to break the cycle, and they were right. They spared us all extraneous errands, and they made our friendship even closer in the process.

Ha! Loved this one and I agree with you, as usual—though I was a happier man before you introduced me to butter boards.

I'll offer my middle ground: I keep sourdough in the freezer and wine in the cupboard. When people come over, I warm some bread and serve it with wine and one tasteful, less-is-more accompaniment. Olive oil with black pepper and fresh lemon zest, butter whipped with a bit of parmesan, that kind of thing. If I can't make it while the bread is in the oven it's too complex.

To your point, nobody wants to stare down the barrel of a ten-item charcuterie board at 3 p.m. Bread, olive oil, and a glass of wine (or espresso if it's morning) seems much more inviting to me.

I really like this, Mari. Cooking and baking for others is a way I indulge my creativity, but I can also feel the burden of expectations, even if they are more in my head than actually spoken aloud. One thing I’ve tried to get comfortable with is I don’t make coffee in the house, only tea (because I don’t like coffee all that much). I worry about it for guests, but I tell myself it’s OK, and people who come over a lot know I won’t have coffee for them. Sometimes they bring their own (for brunch), which is fine by me! Also, I always loved your coffee during our long ago play dates—which shows it’s the company as well as the food that makes time together enjoyable.