It happens about once a month: The New York Times Well section publishes an article suggesting ways we can improve our sleep. The folks over there sincerely want to help, but their advice is useless for true insomniacs like me. Why don’t we just put our phone in another room, stop drinking alcohol two hours before bed, get enough exercise, avoid blue light, avoid—or listen to—brown noise, keep our bedroom dark and cool, and so on? Well, because we’re doing all that already, and it doesn’t work. We’re still waking up at 2am, useless thoughts1 buzzing around in our heads. (And can they please retire the icky term “sleep hygiene”? Might as well toss in “moist” while they’re at it.)

How (Not) to Give Advice—and What to Try Instead

The trouble is, far more people want to give advice than are any good at it. Too often we lack sympathy, relevant experience and knowledge, or a receptive audience. And so, fully cognizant that I am, ironically, giving advice on how (not) to give advice, I’d like to suggest a few questions we can ask ourselves before we blunder in with our “helpful” insights, and a few ideas for what we can try instead.

Ask Yourself, Is It about the Nail, or Are You Just Irritated?

Sometimes we offer advice not because we actually want to help, but because we have begun to weary of others’ tiresome complaints and want to move on to other topics. Case in point, when I was in grad school, I was stuck on my dissertation. I couldn’t get my theoretical framework to make sense, in spite of writing more than a dozen drafts of my proposal and first chapter. I begged my advisor for, you know, advice, and he, likely sick of my fecklessness, said, “You have to figure it out for yourself. Why don’t you just go to the library and read around, and one day it will come to you.” Readers will not be surprised to learn that this bit of mystical wisdom didn’t solve the problem, and that I returned repeatedly to ask him for help. Finally, he suggested—and I swear I’m not making this up—that I take a year off to go work as a dairy maid. Which at least had the virtue of making me laugh. Had he just been reading the chapters set at Talbothays Dairy in Tess of the D’Urbervilles? I have no idea.

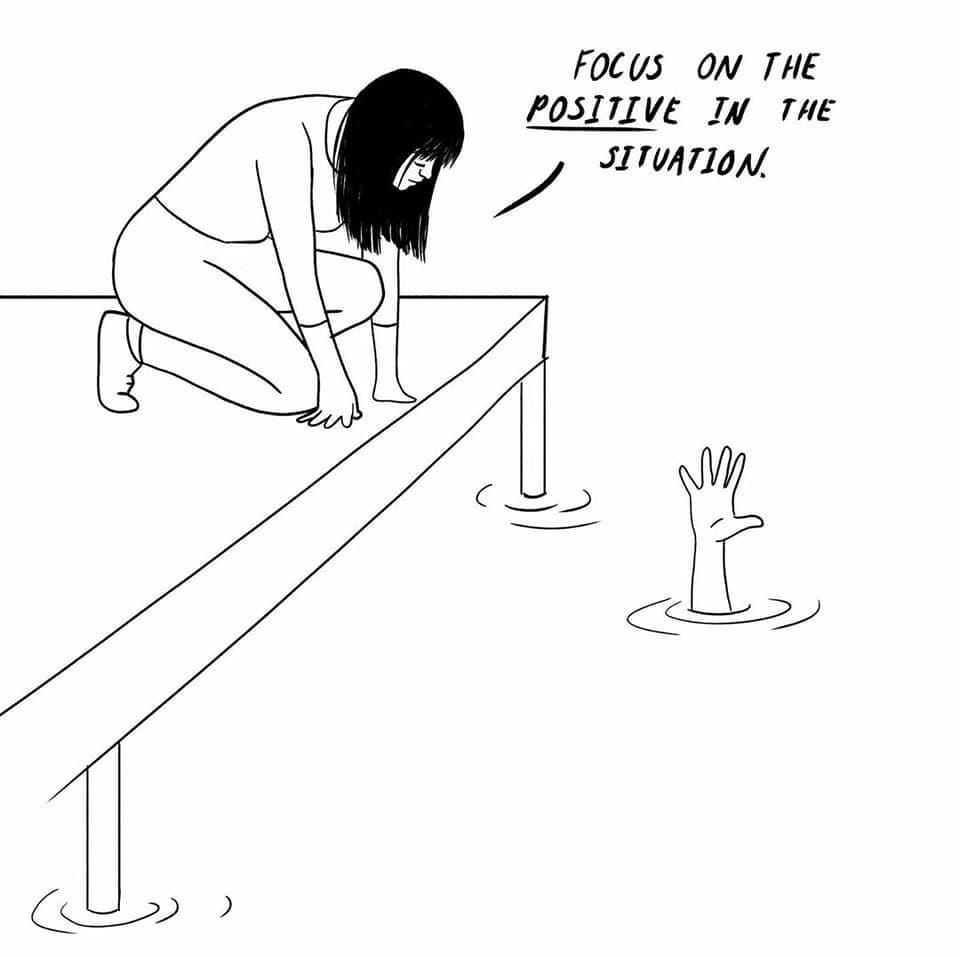

Readers are probably familiar with this video:

Sometimes it really is about the nail, there really is a simple solution, the other person really is unaware of it, and they really will be grateful if we alert them to the problem. For example, about a year ago, a medical student was at hockey match and noticed that the team’s equipment manager had a suspicious mole. She managed to get his attention and to persuade him to go to the doctor. The mole was a malignant melanoma, but they caught it in time. The medical student’s advice saved his life.

This example, and its ilk, aside, it’s more often the case that people’s problems are more complicated than we think, and that our suggestions are clueless at best and shaming at worst. And I don’t mean to judge anyone who gets fed up with other people’s struggles. It happens to the best of us. I once became so disgruntled about having to listen to a friend’s obsession with this guy Robin,2 who had dumped her, that I fixed her up with a friend of mine just so that I wouldn’t have to hear about Robin ever again as long as I lived. If we’re annoyed with a friend who is ruminating over some seemingly intractable problem—or if we have found that our sympathetic ear hasn’t improved the situation—I recommend that instead of encumbering them with advice,3 we discreetly change the subject. I hear there’s this great show, House of the Dragon, that everyone’s talking about.

Ask Yourself, Have You Been Down in That Hole Before and Know the Way Out?

A man falls into a hole and starts yelling for help. A politician walks by and makes a speech but doesn’t do anything to help. A preacher walks by and says a prayer but doesn’t do anything to help. Finally, a friend walks by—and jumps into the hole. “What did you do that for?!” asks the man. “Now we’re both stuck down here!” “Well,” says the friend, “I’ve been down here before, and I know the way out.”

We’ve all had our run-ins with people who regard us from their high perch as we’re floundering down there in the hole, who make judgmental remarks, but who don’t know the way out—the childless onlookers, the unmarried marriage counselors, the naturally thin people who are convinced that if we just tried this one trick, we’d be thin too.4

When my kids were young, nearly every morning we’d walk to our local elementary school. Or, more accurately, my son and I would walk, and my daughter—who is disabled—would ride in the stroller. One day I was returning from drop-off, empty stroller in tow, and a couple of older ladies passed me and asked where the baby was. I explained that I had just dropped her off at school. “At school? How old is she?” “Six,” I replied. “Six is much too old to ride in a stroller!” they scolded. “Why don’t you just make her walk?” Readers, I usually try to be a bigger person than this, but I admit that I took great satisfaction in the look on their faces when I told them why we needed the stroller. Those older ladies had not been down in the hole with me and other moms of disabled kids; if they had been, they would have recognized right away that the stroller was for special-needs children.

If we care about a friend who is struggling, but we have never been down in that particular hole, I recommend that instead of advice we offer practical help: “That sounds tough. Do you want to talk? Or how about I fix you a meal, do your laundry, take your kids out for pizza, clean up your kitchen, or help in some other way?”

Ask Yourself, Did They Ask You (and Do You Know the Answer)?

A few years ago, the child of a college friend had a health crisis. On Facebook, my friend asked for our prayers and ended her post with the plaintive request that no one give the family any more medical advice. This request was revealing; my friend and her husband are both doctors and yet clearly had already been on the receiving end of unwanted and ill-informed advice. If we are itching to give advice but haven’t been asked and can’t help anyway, I recommend that we purge this impulse by reading advice columns. I’m serious! We can get vicarious satisfaction from articles in which the authors straighten people and their tangled problems right out.

If, on the other hand, someone has asked for our advice and we do know the answer, we can rejoice that we are in the rare situation where our advice is both welcome and useful. For example, when I was a new high school teacher, I went to my mom, a veteran special-ed teacher, nearly every day for advice. It started even before classes began, when, at a planning meeting, several teachers warned me about one of my students and told me that I would have to watch out and would have my hands full. Worried, I called my mom, and she shared some advice that is among the best I’ve ever received, not just for that student, but for all my interactions:

You’re just going to have to decide that you’re going to like this kid.

It worked! It turns out that deciding ahead of time to like someone is more effective than going in assuming the worst. Who’d’a thunk it?

Or Ask Them

To return to my erstwhile dissertation. While I was trying to decide what to do, I took academic leave (but not, I hasten to add, to be a dairy maid!). This prompted countless people to exclaim in exasperation, “Why don’t you just write it?” This question was unhelpful, to say the least.5 However, one friend did ask a useful and clarifying question. Himself a PhD dropout, he asked me, “Since you’ve taken leave, how many books related to your dissertation have you read just because you wanted to?” Whoa. I told him zero. “There’s your answer,” he said. “If you were actually interested in your topic, you would still be reading about it even when your professors aren’t making you.” I took his words to heart, quit for good, and have never, not for one single moment, regretted my decision.

It can be tempting to rush in and take over instead of asking questions that guide people to their own solutions, but it’s often better to ask than to answer. Here’s a final story: I was an adjunct professor for a few years, and one of my students was truly wonderful—insightful and imaginative as well as a fantastic writer. One day, she came to my office hours with a dilemma. Her boyfriend wanted her to drop out of college and move to where he lived to marry him. I got a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach. She was only nineteen, her boyfriend was much older, and isolating someone from friends and family is a warning sign of future abuse. It took all my willpower not to preach at her. Instead, I asked her how she was feeling and what her gut was telling her. We talked about her doubts for a bit, and then I asked her why she had come to me, since I don’t exactly hide my feminist opinions, instead of to someone else. She reflected for a moment and then said that she had been hoping I would talk her out of it. Reader, she didn’t marry him. Whew!

Even when it really is about the nail, even when we’ve been in the hole before and know the way out, and even when we’ve been asked for advice, we can still try following psychologist Harriet Lerner’s recommendation, “Don’t just do something! Stand there!” And then ask, and listen.

Some Examples of Terrific Advice

In preparing to write this article, I asked friends and family for the best and worst advice they’ve ever received. Below are quotes that they’ve kindly allowed me to share.

About giving advice:

The biggest challenge for me in giving advice . . . is not to become invested in the person following my advice. Especially when I’m convinced it’s dynamite advice. This applies to teaching as well. The student always needs room to breathe his own air.

About careers:

Estimate how long you think a project will take. Then multiply by ten. [Another version is multiply by pi.]

Everyone works hard whether they make good money or not. So you might as well train for work that pays well.

We think God wants you to leave the seminary.

It’s never too late to give up.

About marriage and family:

He said stop fooling around, find a good man, get married and start a family. He was very blunt and traditional. And 100 percent right.

Don’t marry anyone who you wouldn’t trust to keep a baby alive.

Some Examples of Terrible Advice

About careers:

When I was unemployed once, my dad said I should become a highway patrol officer. My dad means well, but I would hate being a highway patrol officer. First, I am not that fond of driving, second, I do not like guns, and third that uniform just looks uncomfortable to me.

Unironically, the worst advice I ever received was not to use the word “said” when writing fiction, because apparently it was repetitive or whatever.

An older woman with a shriek as I graduated from college in 1970, said, “But you don’t even know how to take shorthand? How will you ever find a good-paying job?”

About marriage and family:

Forget that he cheated on you while dating. He won’t do that once you’re married.

You should date him. He’s the best boyfriend I ever had. Said by his ex-girlfriend.

My personal favorite, Follow your heart! It will never lead you wrong!

And finally, advice my friends wisely ignored:

Always hide that part of yourself; being different will only cause you problems.

Don’t have kids. You’ll enjoy your life! [Said by her own mom.]

On the way to my dad’s funeral: “You should put on some lipstick.”

How about you, readers? What’s the best (or worst) advice you’ve ever received? Have you given especially good advice? What happened? Please share your thoughts in the comments!

The Tidbit

Let’s end with a sweet, romantic story about good advice, from my friend Kathy. When Kathy was in her early twenties, she and her sister had a close friend, Roger. One day Kathy’s mom gave the sisters this advice: “If one of you doesn’t marry Roger, you are both crazy!” Kathy was worried that her sister liked Roger, so she told him, “If you want to date Cynthia, it is ok with me.” Roger said, “You sisters certainly are loyal! Cynthia called me the other night . . . and she said the exact same thing you did!” A few months later, Kathy asked Roger for advice about what they should do, and without blinking an eye, he said he wanted to marry her. Kathy said yes! (And don’t worry about Cynthia—she met her future husband on the day Kathy and Roger got engaged.) And the advice paid off: Kathy and Roger have been married for more than fifty years.

For example, I once lay awake for hours trying to reproduce in my head the layout of every home I had every stepped foot in.

May his name be blotted out.

H/t Samuel Johnson.

As the saying goes, if losing weight were so easy, everyone would have done it already.

Readers of my lengthy essays have no doubt noticed that I have no problem cranking out the verbiage. The problem with my dissertation was not writing it, but rather getting my advisors to sign off on what I had written.

Luckily that advice about being a highway patrol officer was not given by Mari's dad. Posted by Mari's mom

Great advice: always go pee before you leave.